Jan

2021

Can the passives bull market continue forever?

DIY Investor

18 January 2021

This is not substantive investment research or a research recommendation, as it does not constitute substantive research or analysis. This material should be considered as general market commentary.

We examine what the trend to passive investing means for active investment strategies…

We examine what the trend to passive investing means for active investment strategies…

Passive investing has, it seems fair to say, attracted a fair few fans globally. (Indeed some have taken it even further, and are now investing passive aggressively.

Whenever they’re asked for their opinion on their index fund’s top holdings, they simply respond ‘never mind’).

Whilst passive investing was primarily championed as a practical solution by Jack Bogle and Vanguard, Francis Galton’s observations on the wisdom of crowds can highlight some of the underlying intellectual justifications for this type of investment.

In 1906, whilst attending a livestock fair, Galton observed over 800 villagers attempting to guess what the weight of an ox would be once it had been slaughtered and dressed.

Despite wide disparities in estimates, the median guess was exceedingly close to the actual result. The collective wisdom of the crowd had, in fact, produced an accurate estimate.

Active investors make a judgement over the price of a security and assess it relative to the judgement of the market. Buyers and sellers are assessing the news flow, and determining at what price they are happy to transact. The balancing of these interests is the process of price discovery.

Passive investing does not attempt price discovery. Instead, what matters is the size of the asset: as it gets larger the passive investor buys more of it, assuming that the wisdom of crowds gives a good enough estimate of the value of a security. Passive investors are therefore piggybacking off of the price discovery research of others. This leads to the obvious problem: as the share of passive investment grows, who is doing the research?

Remora Fish Asset Management – in desperate search of liquidity

In small doses, relying on others to determine appropriate market prices and passive investment serves the market very well, in a manner akin to the remora fish. The trouble is, in nature the remora fish never grows to such a significant degree that it consumes or overwhelms the host.

This increasingly does not seem the case with passive strategies now. JPMorgan estimated, back in the distant past of 2019, that over 90% of settled trades in the US equity market are between passive participants.

In other words, over 90% of trades settled in the market were price/value insensitive or indifferent. This IS a new phenomenon: as recently as 2006, over 70% of trades were settled between fundamental (i.e. price sensitive at the point of trading) participants.

Moreover, some estimates suggest that well over half of US shares are now held passively, with this number continually growing; and this does not account for active stakes which do not themselves trade (such as cross-shareholdings).

Over 100% of gross equity flows are into passive investment vehicles (i.e. active flows are negative). In addition, aggregated estimates from Fidelity and Vanguard suggest that over 90% of US 401(k)s are now invested in target-date funds; passive investment vehicles which reflexively adjust asset class exposure dependent on the age of the holder.

It is also estimated that over 50% of Vanguard 401(k)s have only one asset: the ubiquitous target-date fund.

More and more flows (and flows drive prices) are, thus, price insensitive, as are most trades. This helps explain the valuation insensitivity of US stock markets for much of the past decade.

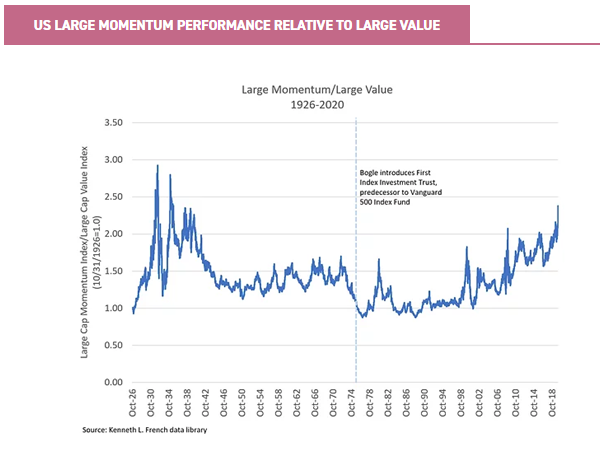

Passive investing essentially represents a momentum strategy: funds flow to the largest companies, without regard to valuation, causing their market capitalisation to grow and generating even more demand.

Unsurprisingly therefore, the performance of the US market has clearly swung in the favour of momentum factors since indexation became available, and as the weight of flows in recent years has swung ever more that way thus has momentum’s outperformance become more acute.

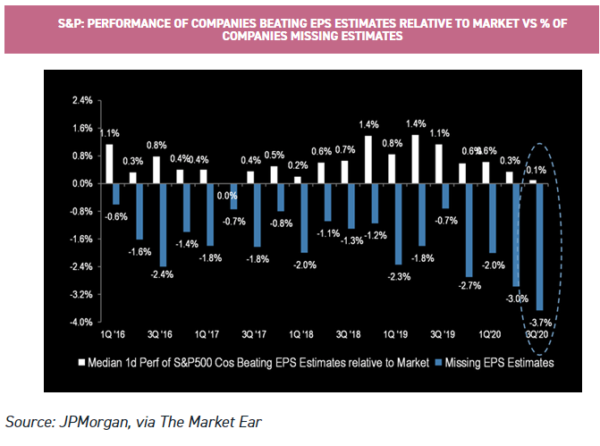

One of the other phenomena, caused by this trend towards passive investing, is periods of heightened volatility around earnings announcements and other events, amid a general trend towards low volatility in the ordinary course of events.

Passive flows are insensitive to valuations or outlooks: they simply buy at market weight and market prices, and so they tend to dampen volatility for the most part. In general flows are structural, with variances being a reflection of demographic trends (more below).

Marginal active buyers or sellers will likely remain corporations themselves, pro-cyclically buying back stock when they are cashflow abundant and issuing stock when economic contractions may require cash injections to maintain operations.

So, whilst some passive vehicles are expressions of short-term tactical allocations, great bodies of trades are now placed with one another by passive vehicles with very few active price setters on the other side of trades.

However, as Moses discovered, liquidity can vanish very quickly. When active investors do want to trade, for example when earnings beat or miss expectations, there is no price at which the passive investor will get involved.

The ever smaller group of active managers have to provide the bid, and so volatility increases. Consequently, we enter a state of paradox: earnings and operational updates are at an individual level increasingly irrelevant to the price of a security.

Yet at an aggregated level, they are more important than ever, and volatility spikes are likely to occur on any market-level disappointment at a level disproportionate to the quantum of any update.

We would argue that extreme divergences in sector and stock performances in 2020 not only reflect sharp differentiations in perceived future viability of different company models, but also the fact that market liquidity is so acutely tight even in many names relative to flows.

Evidence abounds, for example, that a surge in retail interest in buying call options in certain stocks (such as Tesla) requires the market maker to buy stocks in said company to hedge their book.

As these orders are aggregated, they are consequentially bunched together in a very large institutional order.

This order flows into an illiquid market with few active sellers (remember over 90% of trades are settled between passive vehicles) which axiomatically bids up the price of the stock. Passive flows further bid up the stock in recognition of its increased weighting.

A whole glass of juice from just one sack of oranges?!

As Mike Green, of Thiel Macro, has highlighted, it seems likely that this trend for increased indexation is only going to be exacerbated, with younger generations more likely to save into passive vehicles.

This situation would appear to be both a consequence of the intellectual triumph of passive in the popular conscience, but also of regulatory requirements which makes precisely such vehicles more attractive to, for example, allocators of company pensions.

Whilst other factors, such as regulatory capture, have, in our opinion, benefitted large caps in an operational sense.

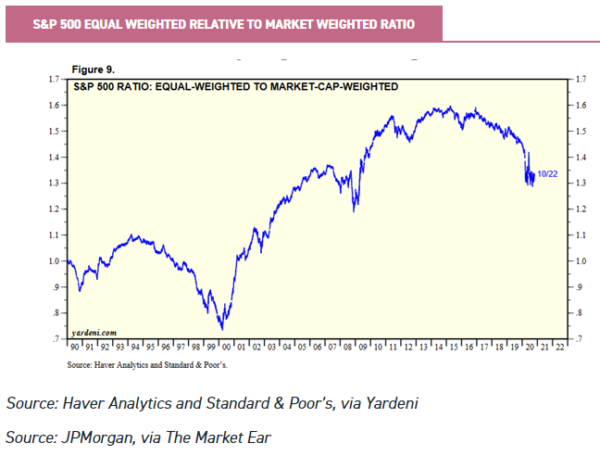

However, to us, the incremental shift to a market-cap weighted index outperformance over equal weighted, indicating less intra-market dynamism, in recent years seems indicative of the impact of passive flows on relative returns.

That small-cap US equities, as represented by an iShares ETF, trade on a substantial discount to their large-cap counterparts on both an earnings and book basis, despite the typical assumption of superior growth potential, seems further indications of the impact of indexation.

Surely (in)flows are a one-way street though? After all, why would anyone ever sell-out of the market, when you can simply live off your investment income.

The average US baby boomer (born between 1946 and 1964) has c. $152k of retirement savings, according to a 2020 study by the TransAmerica Centre[2] for Retirement Studies.

Vanguard’s 2020 Retirement Fund presently yields c. 1.87% p.a. on a trailing basis[3] ; even this is in excess of the trailing yield of c. 1.7% on the S&P 500[4] .

On the basis of the Vanguard product, an average retiree this year can reasonably expect a retirement income of c. $2,842 p.a. from their private savings. Clearly this is a subjective matter, but it seems likely to us that many will not have the option of holding their savings to eternity, and will instead have to realise capital to fund retirement costs.

As the population ages, the capitalising of holdings will not even necessarily prove the main impediment to asset values. Target retirement date funds automatically reweigh holdings away from equities and risk to bonds, as the holder matures.

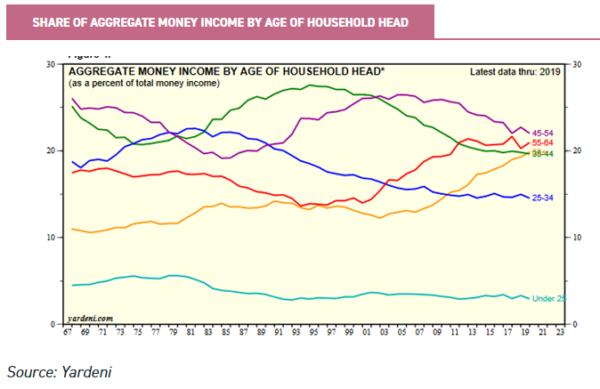

With those aged 55+ being the only groups seeing aggregated shares of income rising, and typically having the greatest marginal propensity to save, an axiomatic flow of capital from equities to bonds is to be expected in the coming years.

Contrary to what we have experienced previously, this suggests we face a structural headwind to market-level valuations in the future, as the momentum trade reverses.

Blessed are the meek, for they inherit the Earth market[5]

Those that boldly try to strike out into active solutions should benefit from such an irrational pricing environment though, no?

This does not, in fact, appear to be the case. In part the reality is a reflection of what we have outlined above. When a majority of the market is price insensitive, the value of security is only a reflection of what someone is willing to pay for it.

Buying superior fundamentals is essentially worthless, unless there is a liquidity bid for it. Perception becomes reality in a manner worthy of Lysenko as flows follow flows.

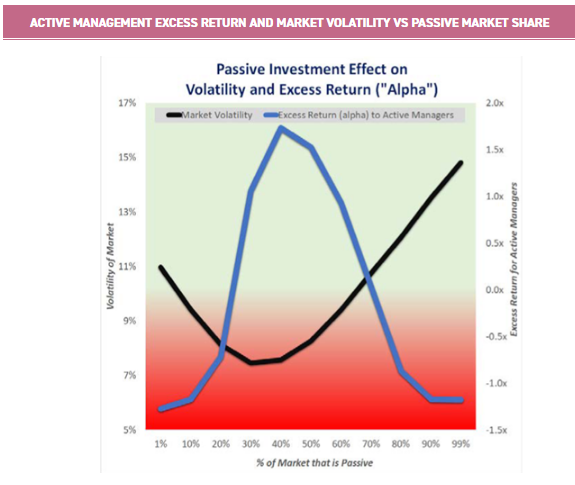

Christopher Cole of Artemis Capital Management has demonstrated this trend, using a simulated model which examines the potential for excess returns for active managers against a full range of passive market share.

As can be seen below, the model suggests that, as passive market share increases, it does indeed offer greater opportunities to active managers, whilst the impact of passive flows dampens market volatility. However, as this becomes the majority of the market, the effect is dramatically reversed in both instances.

Rage against the machine, but don’t fight it (yet)

Of course, recognising an issue is one thing, actioning it is another. One could argue that, in a variant of the prisoner’s dilemma, there is no real solution available beyond a near-universal supplication of near-term self-interest in the name of long-term self-interest.

But active strategies will likely, in our view, continue to find the current environment a challenging one for the time being, as regulators continue to favour low-cost passive solutions with, seemingly, no performance concerns as the most appropriate default savings option for most investors.

BH Macro (BHMG) and BH Global (BHGG) both have investment structures designed to thrive in the sort of volatility spikes a passive dominated market is likely to prove prone to.

Whilst the strategies are opaque and subject to high degrees of variation, the traders within them look for deeply asymmetric payoff opportunities.

Typically, periods of low volatility offer the ability to take potentially highly convex positions with limited downside and significant upside, as a result of the input of implied volatility into standard options pricing models (with higher implied volatility typically increasing the cost of hedging in this manner).

As sharp market moves occur, so to implied volatility generally rises, and typically so will the price of an option (provided it is directionally appropriate).

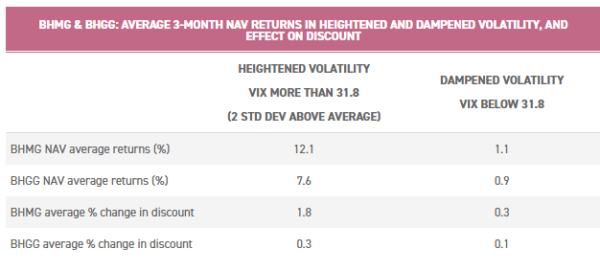

We can see in the table below the 3-month NAV returns in BHMG and BHGG in periods of low volatility, and in periods of elevated high volatility (high volatility is here defined as periods where the VIX volatility index is more than two standard deviations above the 10-year average (c. 31.8), whilst low volatility is all other data points).

We have also included the impact upon BHMG and BHGG’s discounts during these time periods: as can be seen, they actually tend to see share prices outperform NAV. As such, we think these can continue to offer a welcome potential source of diversification at times of market stress.

Of course, investors may wish to retain exposure to the domestic US economy whilst eschewing public markets as a result of the issues outlined above.

Private equity trusts, such as NB Private Equity Partners (NBPE), offer exposure predominantly to the US, with private capital making an assessment of the likely return available to them from an investment.

A mixture of the low cost of capital, longer-term investor outlook and indexation has seemingly also encouraged many companies to delay a public listing until they reach a much greater scale.

Value realisation on the public markets should attract automatic bids from indexers at the float level, making more ambitious valuation targets feasible. And yet, perhaps because of the understandable concerns of investors about the inherent leverage and underlying illiquidity in private equity, NBPE trades on a discount of c. 26% at this time. We have updated out profile on NBPE this week – click here.

As and when net equity flows are increasingly driven by passive investment vehicles, actions by companies themselves when there is an illiquid market in their shares can potentially impact share prices sharply too.

Share buybacks should prove supportive, especially when placed into a market with an absence of sellers. In this regard, we think the ongoing strategy of management engagement pursued by the managers of Third Point Investors (TPOU) within their ‘activist’ or ‘constructivist’ portfolio allocations can potentially unlock increased value for shareholders in the future.

Methods of unlocking corporate value need not necessarily require buybacks, and we believe that there are numerous routes to corporate ‘self-help’ potentially available to the manager in seeking to boost equity returns without reliance on market-level reassessment and concomitant repricing of a company’s ‘value’.

Similarly, ‘event-driven’ investing may have drivers of value realisation independent of a reliance of wider market interest, whilst the ‘long equity’ book is primarily concentrated amongst companies which are already significant index constituents.

TPOU trades on a discount of 20% currently, and the board themselves are reviewing the buyback policy during Q4, which could potentially see them become more aggressive. We discuss the potential opportunity in this recent note.

Conclusion

Passive is big business, and it is likely here to stay in our opinion. We believe this wholesale move towards passives is a serious issue for both the domestic US and global economy, with capital allocation decisions now swayed increasingly on the basis of historic success and not on the need for capital.

Productivity growth has trended weaker for many years, and indexation seems likely to remain at least partially culpable (though other factors such as low interest rates, regulatory capture and oligopolistic corporate dispersions have clearly contributed too in our opinion).

For active investors in the US, the Rubicon has been crossed. This situation could increasingly become an issue in the UK too in coming years, given the pressures from automatic enrolment in pensions and the use of lifestyle/target-date funds which are predominantly passive.

Similar risks are at work across much of the developed world, but the problem is most acute in the US.

Passive outperformance has, it seems, become a self-fulfilling prophecy, with liquidity dynamics and price insensitivity – instead of supposed greater market efficiency – being seemingly more tangible factors in the oft-noted difficulties in the abilities for active US managers to outperform compared to their peers.

Investors will, however, surely want to continue to allocate to the US economy, which remains the largest in the world. In our view the market structure offers the likelihood of increasingly elevated volatility in the coming years, as passives’ share continues to grow.

Investors would seem well-placed to hold strategies to account for the market structure observed: either to maximise upside as a vicarious consequence of the policy implications, or to offset market downside at moments of stress and provide diversification.

[1] https://www.logicafunds.com/policy-in-a-world-of-pandemics

[2] Whilst we respect and thank the organisation for their work, we will not humour them which it comes to their misspelling of the word ‘centre’

[3] https://investor.vanguard.com/mutual-funds/profile/VTWNX

[4] https://www.multpl.com/s-p-500-dividend-yield

[5] Elon Musk certainly believes this is true, but only after him and the other cryogenically frozen bold souls jet off to Mars in 2 million years’ time. Long duration assets indeed.

Click to visit:

Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future results. The value of investments can fall as well as rise and you may get back less than you invested when you decide to sell your investments. It is strongly recommended that Independent financial advice should be taken before entering into any financial transaction.

The information provided on this website is not intended for distribution to, or use by, any person or entity in any jurisdiction or country where such distribution or use would be contrary to law or regulation or which would subject Kepler Partners LLP to any registration requirement within such jurisdiction or country. In particular, this website is exclusively for non-US Persons. Persons who access this information are required to inform themselves and to comply with any such restrictions.

The information contained in this website is not intended to constitute, and should not be construed as, investment advice. No representation or warranty, express or implied, is given by any person as to the accuracy or completeness of the information and no responsibility or liability is accepted for the accuracy or sufficiency of any of the information, for any errors, omissions or misstatements, negligent or otherwise. Any views and opinions, whilst given in good faith, are subject to change without notice.

This is not an official confirmation of terms and is not a recommendation, offer or solicitation to buy or sell or take any action in relation to any investment mentioned herein. Any prices or quotations contained herein are indicative only.

Kepler Partners LLP (including its partners, employees and representatives) or a connected person may have positions in or options on the securities detailed in this report, and may buy, sell or offer to purchase or sell such securities from time to time, but will at all times be subject to restrictions imposed by the firm’s internal rules. A copy of the firm’s Conflict of Interest policy is available on request.

Commentary » Exchange traded products Commentary » Exchange traded products Latest » Investment trusts Commentary » Investment trusts Latest » Mutual funds Commentary

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.