Mar

2022

Regime Change

DIY Investor

8 March 2022

Ahead of our spring conference, we ask whether investors need to junk their portfolios to start over again….

Ahead of our spring conference, we ask whether investors need to junk their portfolios to start over again….

Disclaimer

This is not substantive investment research or a research recommendation, as it does not constitute substantive research or analysis. This material should be considered as general market commentary.

What did you learn from the 2007/2008 financial crisis? I learned that just because there’s a long queue of people in the street, it doesn’t mean there’s something worth waiting for at the end of it. (If you didn’t have an account with Northern Rock they were actually quite rude when you got to the front.) Nobel prize winning economist Paul Krugman learned that a model of the economy should include a model of the banking system1.

Joking aside, how you explain the impact of monetary policy on the economy after the financial crisis is crucial for how you interpret the current outlook, and economics is a young science with few good answers (or too many conflicting ones in fact). Some economists have taken the disinflationary environment experienced from 2009 to 2020 as evidence that governments are actually able to print money with impunity.

Others built a model of the economy in which demographics and technology are disinflationary forces which monetary policy would be unable to escape over the medium term. One potential danger for central bankers, and for markets, is if we have all learned the wrong lessons from the post-2008 economy.

What if the reasons inflation stayed low post-GFC were specific to that crisis? What if the economic theories built to explain the experience from 2009 onwards are leading us astray? Looking at the global economy right now, we think the key risk for investors is that inflation gets out of control and remains persistent for longer than expected. This has many critical implications for investors.

In our spring virtual summit, which runs from March 15 to March 17, we will hear from managers investing around the world about the outlook for their trusts (you can sign up here). It seems like the perfect time to be resurveying the world economy in search of new ideas given the huge uncertainty in markets. Below we discuss why we think preparing for persistently high inflation could be a critical consideration. We also discuss some potential implications for asset allocation and various markets around the world.

Central banks are worried about employment, not inflation per se

The US Federal Reserve has a dual mandate to focus on ensuring full employment and price stability (plus technically there is also a third mandate, which relates to the maintenance of stable moderate interest rates, but this flows from the other two).

In the conventionally accepted Keynesian model of the economy, what the Fed is really concerned about is employment: demand-pull inflation is an indication of excessive demand, which eventually leads to a recession and a rise in unemployment. If the Fed were to respond to the current supply-push inflation by raising rates it would, following the logic of Keynesian theory, be preventing employment and reducing business activity.

This would ultimately lead to lower inflation, but only by crashing the economy, and it’s hard not to see this as suboptimal. Therefore, insofar as the Fed interprets rising prices as being supply-led, it is likely to have a deep bias to delay.

This is compounded by the failure during the last cycle of the Phillips curve, the basic model of the trade-off between employment and inflation. From 2013 onwards, many economists (and fund managers) saw falling unemployment numbers as indications inflation would rise and the Fed would raise rates.

However, that never came to be. What became apparent was that the way that economically inactive people were classified was underestimating slack in the labour market. People working part-time or those out of the workforce came back into employment when the opportunity presented itself.

A low unemployment number is therefore viewed with suspicion by this generation of central bankers, who don’t want to be fooled twice. (This failure was probably a key motivator for many of the overarching economic theories about the deflationary forces in the economy.)

We have potentially a similar position in 2022. Unemployment numbers are low, while newspapers are full of stories about the ‘Great Resignation’ and a generation apparently keen to live off dog-money and monkey pictures rather than working (truly a dream).

Central bankers are likely to be deeply suspicious. A window into their thinking can be seen in a paper from the San Francisco Fed published in June 2021, which highlighted that 3.4m people had left the workforce since the start of the pandemic. The authors estimated that US unemployment was around two percentage points higher once this was accounted for, at over 8% rather than 6%.

Whether these people do want to work or not, central bankers are likely biased towards assuming they do. This line of thinking means they are likely to be much easier on the brake pedal, increasing the likelihood of there being higher inflation for longer.

The ability to spend is much higher than it was in 2008

An explanation for the low inflation after 2008 comes from Richard Koo, who coined the phrase ‘balance sheet recession’. The basic thesis is that the private sector, both in the US and the developed world as a whole, had massively overexpanded and therefore had to deleverage following the crash.

This was a deflationary force sucking cash out of the economy, which offset any inflationary impulses from quantitative easing and low rates. If this is true, then the picture is totally different this time around. This crisis was caused by the pandemic and the lockdowns imposed to handle it.

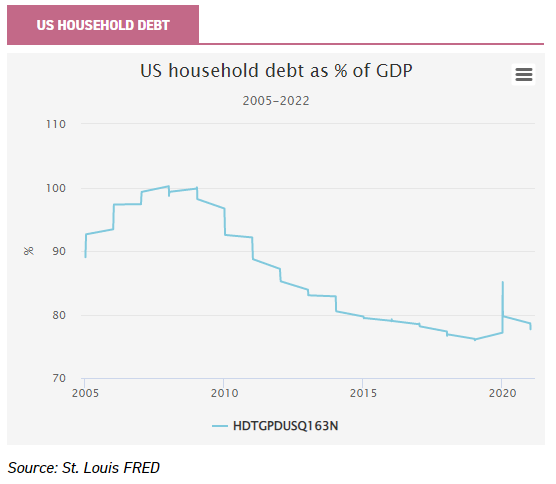

To the extent consumers retrenched it reflected there being nothing to spend on rather than worsening personal circumstances, while incomes and debt levels were maintained at healthy levels by government grants. The result is that far from having to deleverage, US households are in cracking shape, with plenty of cash to spend and chase prices higher. Below we show US household debt as a percentage of GDP. It remains near post-GFC lows, and very different to the picture in 2008.

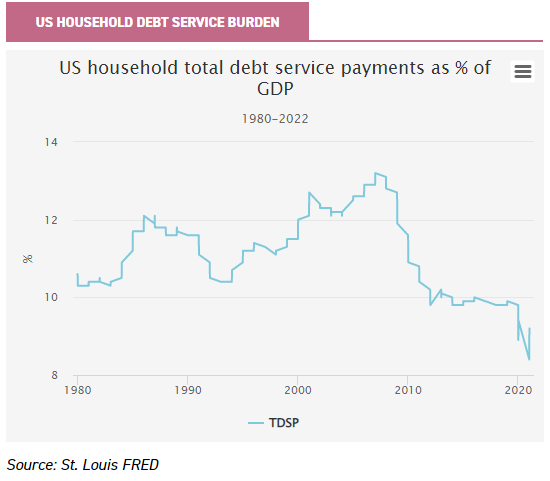

Even more significant to the ability to spend is the cost of servicing those debts, which have been decreased by falling rates. The below graph shows household debt service costs as a percentage of GDP. We have data going back to 1980, and it hasn’t been near to this low over that time.

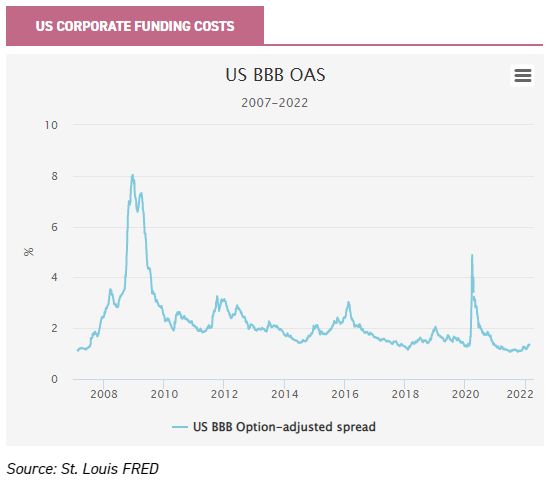

One way inflation slows is people stop spending as they can’t afford things. Yet the above suggests there is plenty of scope for consumers to pay higher prices, and the same is true for corporates too. Below we show the average spread over treasuries paid on US BBB debt (non-financial). It is near to all-time lows. Given this looks at prices in the secondary market, a possible better indication of low debt costs to businesses could be the average coupon on recently issued debt.

Fitch reported that in the second half of 2021 US IG bond issuance was at near record levels, with an average coupon on debt in the second half at record lows of 2.6%. The average coupon on outstanding debt in the BBB segment was 3.9%. At the bottom-up level, credit managers we speak to seem optimistic right now: companies have clean balance sheets and plenty of scope to spend. While this is positive, it does increase the chances that inflation will get out of control.

Yet there may be expectations that banks will throttle back on lending as they did after 2008. However, this is unlikely as the banking system is in much better shape. Following Basel III, banks have had to ratchet up their capital significantly. US data going back to 2010 shows how the new Tier 1 capital ratios have risen from below 12% to almost 16%. The latest release from the ECB suggests EU banks reported 15.6%, and BoE data for UK banks is 16.5%. Banks have plenty of scope to take risk, as Basel III insists on a 10.5% minimum.

Real rates are negative and will remain so

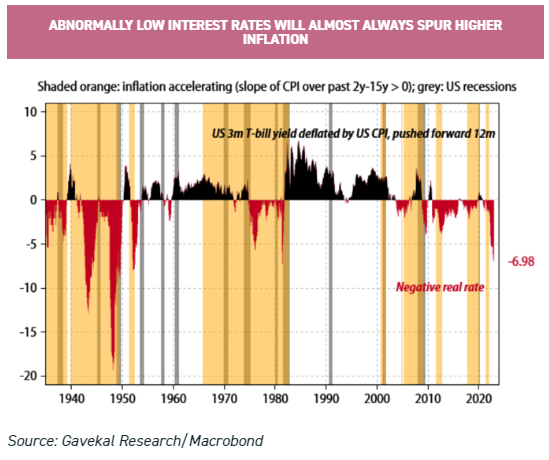

It looks like central banks are going to be biased towards letting inflation ride, for good and bad reasons. The experience of the last cycle and the last crisis might lead bankers, politicians and investors to have unrealistic expectations, and for inflation to be higher and more persistent than they expect. Charles Gave of Gavekal Research points out another factor that points to high inflation: negative real rates.

Looking back over US history since 1960, he argues that negative real rates have led to inflation one year ahead, with the exception being the post-2008 experience. We have already suggested that low inflation after 2008 was due to a debt deflation going on in the background, counteracting the inflationary impulses of monetary policy. And we have also shown evidence that this time the picture is very different.

Gave follows a similar line of thinking, unpicking three deflationary shocks: the GFC, the euro crisis and the COVID crisis. If negative rates cause inflation one year ahead absent a deflationary shock, and a deflationary shock is absent, then the current spike in inflation will not decline to a pre-COVID trend – in fact, the Fed may have already made a policy error in keeping rates on the floor this long.

Conclusions and investment implications

We have presented some reasons to think economists and central bankers may have been biased by the post 2008 experience to think there are persistent disinflationary forces in the economy which they need to counteract. We have also presented some reasons to think they are wrong, and have already kept the foot off the brakes too long.

Gave thinks that negative real interest rates and accelerating inflation (such as we are experiencing today) are both serious warning signs of inflation ahead – and agrees that central banks are behind the curve. As for investment implications, he views this as being negative for long-duration assets, potentially meaning more pain for bond investors and speculative growth stocks. Yet in his eyes it is better news for commodities, including energy and gold.

On 17 March we will hear from Evy Hambro, the manager of BlackRock World Mining (BRWM), on his outlook for commodities. Mining has had a renaissance in the post-COVID world, so is this trend set to continue? Does Evy think gold could shine once more, after its disappointing performance during the inflationary spurt so far? Perhaps central banks being seen to lose control could make the difference. Yet if commodities have a good run, what does this mean for commodity producers versus importers?

On 16 March we will hear from various emerging markets managers, as the managers of abrdn China, Asia Dragon and Ashoka India Equity discuss their portfolios in the context of the new environment. One Asian market increasingly getting the attention of regional fund managers is Indonesia, which could stand to benefit from rising commodity prices, and there could be some pandemic reopening beta still to harvest there too.

As for China, one interesting driver behind its equity market could be that its central bank is easing policy while the US and Europe are tightening theirs – could trends therefore be different in that market over 2022 and beyond? We will also hear from Matthias Siller, manager of Barings Emerging EMEA Opportunities (BEMO), on 16 March. Matthias’s region contains some of the world’s largest energy producers and some important miners.

High inflation would seem to be better for value stocks than growth stocks, and day one of the event has a value theme. To varying degrees, all five managers have significant value elements to their style. BlackRock Latin American (BRLA) has significant exposure to the commodity complex, through its position in Brazil. BlackRock Sustainable American Income (BRSA) has a value tilt, but also has a strong sustainability ethic which influences which companies in the energy and mining sectors it will invest in, so this could interest investors keen to invest in these sectors but wary of ESG issues.

It’s not all about value and commodities, though. In fact, if bankers remain reticent about raising rates for the reasons we have outlined above, stocks may be pricing in more rate hikes than will transpire, which could relieve the pressure on growth strategies. In any case, whatever the economy does, technology continues to advance and throw up long-term investment opportunities – and many stocks are significantly off all-time highs already. On March 17 we will hear from the managers of Allianz Technology Trust (ATT) about the outlook for their portfolio and where they are finding the best opportunities. In our recent note they highlighted the cyber-security and semiconductor themes as increasingly throwing up ideas.

As value has outperformed, ATT has moved onto a discount of c. 7%, which could be an interesting long-term entry point. Baillie Gifford Japan (BGFD) is also growth stock royalty, and is now trading on a modest discount. Japanese long-term rates are showing some movement, too – so could Japan finally get some inflation, and would this be positive for a growth-starved economy?

These are just some of the managers presenting. Please sign up below for your chance to interrogate them on inflation or on anything else. You can view the full schedule at the following site.

1I respect Professor Krugman a lot, but come on.

Commentary » Investment trusts Commentary » Investment trusts Latest » Latest » Take control of your finances commentary

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.