Jan

2022

Is the UK’s debt a ticking time bomb?

DIY Investor

17 January 2022

This is not substantive investment research or a research recommendation, as it does not constitute substantive research or analysis. This material should be considered as general market commentary.

Is the UK’s debt a ticking time bomb?

Our analyst argues Rishi is right to worry about government debt and borrowing…

Our analyst argues Rishi is right to worry about government debt and borrowing…

A common cliché in finance is “the most dangerous words in investing are this time is different”. I would argue the opposite error is equally as dangerous. Assuming that past trends or relationships will continue to hold can lead us astray, with just as serious consequences.

After the 2008 crisis many commentators and managers warned that QE would lead to unmanageable debt levels, leading to an inability of governments to borrow more. On the other hand, spiralling inflation might bring the debt down in real terms.

Of course, none of this happened. QE was successful in smoothing the economic cycle and governments continued to borrow at attractively low rates. As we come out of the latest crisis, which saw a far worse contraction of GDP, some economists and investors seem to have taken this prior period as indicative of eternal truths.

The most intellectually respectable of these (although they might not have been so respected a few years ago) refer to their thinking as MMT. These economists argue that the ability of governments (or is it just the US government?) to issue their own currency means there are no practical constraints on government spending.

What a wonderful message to hear. Unimaginable sums have been spent on bottling up COVID until vaccinations have been rolled out. Now that the peak of the crisis seems decisively to have passed, endless billions are being sought to repair the health service, tackle climate change or dig huge tunnels under the Irish Sea.

So, can we just continue to print with impunity? Newspaper reports suggest that Boris believes we can, while Rishi and his Treasury team are more sceptical. I think there are good reasons to stand with the Chancellor on this matter.

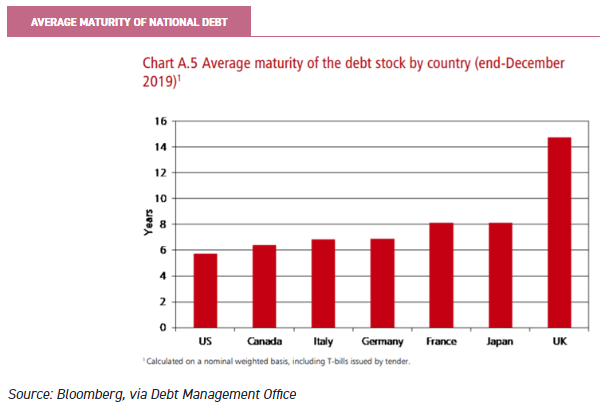

The UK has benefitted in recent years from its debt having a relatively long average maturity. While this means bondholders are more exposed to rising interest rates, for the lender (the UK state) it means that a relatively large proportion of its debt does not have to be refinanced for many years. This has the benefit of reducing the sensitivity of government finances to spikes in short-term interest rates.

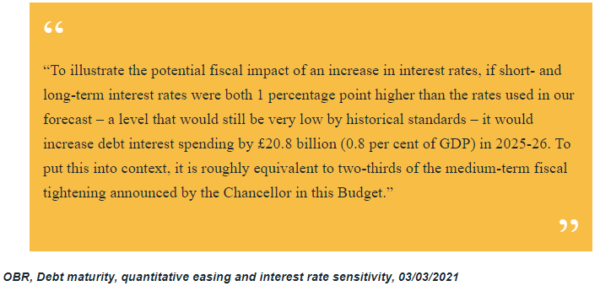

However, as the OBR pointed out earlier this year, when we consider the impact of the huge COVID QE programmes, the picture changes substantially. QE effectively sees the Bank of England buying gilts and creating reserves for financial institutions by way of payment.

In other words, it takes a long-dated debt instrument on which the Treasury pays the coupon out of circulation and replaces it with an account on which the BoE pays a short-term interest rate. When we consider the BoE and Treasury liabilities as a whole, this radically reduces the average maturity of the UK’s debt, and radically increases its sensitivity to short-term interest rates.

The OBR estimates the median maturity of UK debt falls from 11 years to four years when these short-term liabilities are included. This means a relatively modest rise in interest rates could have serious consequences for UK government spending, with a parallel shift in yields of 1% leading to an extra £20.8bn to be spent on debt repayments in 2025.

Proponents of ‘spend now and pay later’ argue that the best route out of our current situation is to grow the economy faster than the rate we pay on our debt. To that end they justify HS2, tunnels and bridges and even sending cheques to every citizen as ways to boost GDP growth, which will allow debt to be paid down in a sustainable way. It’s hard to argue this isn’t the best possible way out, but it is also a very risky course of action.

Bank and Treasury officials have repeatedly justified the ballooning of the government debt burden to MPs with reference to the international market that determines yields.

They argue that the UK is unlikely to be punished by the market for expanding its borrowing so extensively given its peers are following the same course and have similar or worse fiscal positions. While this has been true during the crisis, it may not remain true.

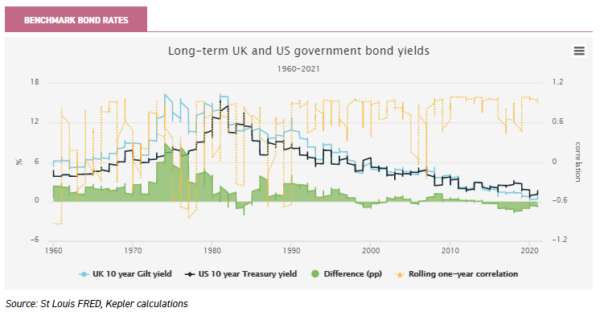

A look at US and UK interest rates in recent decades shows a significant and increasing correlation between them. The below chart shows the benchmark 10-year yields on US and UK government debt. I have also shown the difference between the two in percentage points, in green, and the rolling one-year correlation, in yellow.

The last notable divergence came prior to the pandemic, when stronger US growth prospects and concerns about Brexit pushed US and UK rates in different directions, to the benefit of the Treasury. What worries me – and what I believe Rishi and his gang are increasingly concerned by – is the possibility the divergence might take a different direction.

Domestic investors

UK rates remained lower than the US’s in the period after the Brexit referendum and Trump’s election because concerns about the UK’s prospects led to greater risk aversion in the gilt market. This strongly implies it was domestic investors who were buying.

But the above chart shows a prior example of a crisis seeing UK government borrowing costs rise: during the 2007/2008 financial crisis, the size of the UK financial sector relative to GDP saw a spike in gilt yields as investors worried about the implications for the UK of bank defaults. In this scenario, risk aversion led to a spike in borrowing rates.

Domestic investors were worried about UK government solvency and stepped back. The BoE was able to respond by cutting short-term rates to the floor and implementing the first round of QE.

The worst-case scenario for the UK is one in which the BoE feels compelled to raise short term rates in a crisis rather than cut them.

One way this could happen is if the UK economy lags in a global, US-led recovery. As Treasury officials have frequently stated, low rates are a global phenomenon. What happens if the natural interest rate creeps up in the US and the wider world, but not in the UK?

The nightmare scenario is one in which the UK feels compelled to raise rates in order to prevent capital flight to geographies with better growth prospects and higher rates. The critical issue for me is that the domestic economic conditions, or investors, won’t necessarily be the determinant of UK interest rate policy.

One factor potentially depressing UK rates in recent decades is the shift to liability driven investment by pension funds. This form of asset-liability matching sees defined benefit pension funds seek to neutralise their exposure to interest rates and inflation by buying long-dated bonds and hedging around them.

The shift from a model of investing for growth to one of matching liabilities is a one-off secular change, particularly given the decline in the number of defined benefit pension funds. Some analysts have suggested that ‘peak LDI’ could be reached in the next few years, at which point the well of demand for gilts would have been exhausted, but others suggest it could be as late as the 2030s, using very similar assumptions and data.

Whatever the exact truth, in the decades to come it does seem like a large domestic, relatively price-insensitive buyer is going to slowly disappear from the market. This would leave the Treasury dependent on more price-sensitive buyers like foreign institutions and mutual funds, who are likely to be far more concerned with the growth outlook for the UK than domestic pension funds. This means the UK’s relative economic attractiveness is likely to matter more and more.

To my mind, managing the public finances without taking into account these sort of tail risks would be irresponsible. I noted at the start that assuming past patterns would repeat themselves is dangerous.

The amount of gilts bought under QE programmes more than doubled during the coronavirus pandemic, meaning our starting point is very different from 2009 when the first programme was implemented and again very different from 2019, before the current expansion.

As the OBR highlights, by the end of this financial year, 32% of the public sector’s gross debt (£875bn out of £2.7trn) will be in the form of central bank reserves issued to finance gilt purchases, making our exposure to any spike in interest rates much, much higher. Just because we have recently had a ‘black swan’ event in the pandemic, doesn’t mean we shouldn’t expect another soon. A bit like having a stockpile of PPE, I agree with Rishi we should also make sure we have built a financial buffer against future crises.

For an investor, I think it is wise to hedge these sorts of tail risks. Some readers will remember the likes of Bruce Stout warning of developed world indebtedness after the 2008 crisis, and how that worked poorly for those who shifted their portfolios into the less indebted developing world. I think investing in regions with preferable debt dynamics could be a wiser move in response to the current crisis.

Trusts like Invesco Asia or Asia Dragon look to identify leading businesses in the Asia Pacific region, and both strategies pay close attention to balance sheets and company indebtedness. BlackRock Frontiers and Barings Emerging EMEA Opportunities invest largely in countries with much lower levels of indebtedness, although these less-developed countries could well suffer if there was a debt crisis in the developed world as a whole rather than just the UK.

Finally, owning duration-sensitive assets looks less appealing than it did in the past. A UK investor with the traditional 60/40 portfolio would have a serious exposure to this sort of tail risk event.

Diversifying via alternatives, or into a trust which aims to build a diversified portfolio of such alternatives, could help build in some protection against UK plc going pop.

Ruffer Investment Company could fit the bill, and its holdings in long-dated index-linkers and gold could protect in the sort of environment in which inflation spikes and trust in institutions wobbles, which is one way we could conceivably get to the sort of scenario keeping the chancellor’s team up at night.

Commentary » Investment trusts Commentary » Investment trusts Latest » Mutual funds Commentary » Take control of your finances commentary

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.