May

2022

Getting in on the act: Private markets

DIY Investor

16 May 2022

Private markets could be the next big opportunity for investors….

Private markets could be the next big opportunity for investors….

Private markets could be the next big opportunity for investors; in this first of a series of articles looking at private market exposure and what it brings to a portfolio, we look at private equity, potentially the highest returning area of private markets, but also the biggest risk.

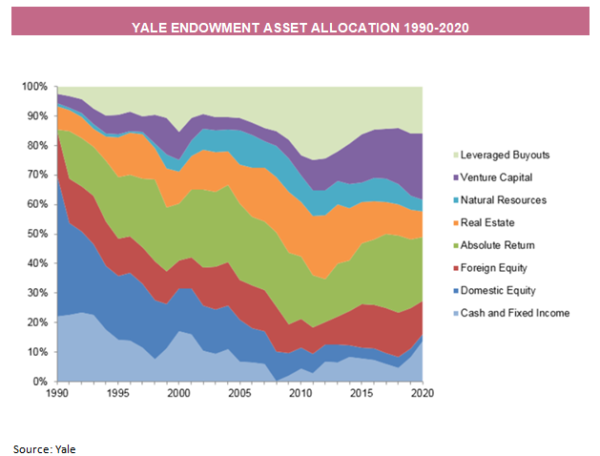

As we discussed in August last year, large institutional investors have long led investing fashions. We highlighted Yale’s transformation of its Endowment portfolio from public towards private assets, as its management embraced illiquidity and risk; over 30 years, it has dramatically increased exposure to non-traditional asset classes. Today, US listed equities account for < 10% of the portfolio; foreign and private equity, absolute return strategies, and real assets represent 90% >. We share Yale’s view that alternative assets (illiquid, private investments) offer greater opportunity to exploit market inefficiencies through active management.

It delivered different returns to standard portfolios; Yale’s Endowment reported a 40.2% investment return, net of fees, for the year ending 30/06/2021, generating $12.1bn in investment gains. FTSE World Index returned 18.9%.

This is icing on the cake for the Endowment, which has outperformed wider equity markets for decades; Admittedly, Yale embraced risk as well as illiquidity, but investors everywhere are taking notice of private assets. The board of Calpers (the US’s biggest public pension plan with $500bn) decided in 2021 on a significant change, increasing private equity by 5% to 13%, and investing 5% of assets into private debt for the first time. The increased allocations are to be funded from public equities, which it views as ‘overheated’ (FT). The investment trust universe is a big beneficiary of investors that agree, with AUM in ‘alternatives’ rising by £11.5bn over 2021 (73% of the sector’s issuance: Numis).

‘This exceptionally strong return is icing on the cake for the endowment, which has outperformed wider equity markets for decades’

The UK Government recently consulted with the pension and investment management industry to change fee caps set up to protect workplace pension scheme investors from high costs.

Capped at 0.75%, many alternative asset managers are unwilling to offer products to these pension schemes. Government is keen to remove barriers for schemes to access illiquid investments.

The consultation sought to determine whether a performance fee could be levied for such assets outside of the cap. In the FT, the Pensions’ Minister recognises that ‘green infrastructure, private equity and venture capital, fits well with the long-term horizons of DC [defined contribution] schemes. Such investments have the potential to provide better returns for members as part of a balanced portfolio and help to sustain employment, our communities and the environment’.

What are ‘private assets’ from an investment perspective?

We define private assets as unlisted investments; as a result, they are illiquid. With no ready market, prices/valuations are negotiated. Part-ownership is rare, so being a controlling shareholder in such assets requires significant management expertise over and above a listed-equity manager. In capitalist economies, private assets dominate; many high street brands are unlisted or private, but are far from niche.

‘Private capital has allowed companies to grow to a global scale without having to list on a stock exchange’

Historically, companies found stock markets an important source of equity capital they needed to grow. Increasingly, private capital has allowed companies to grow to a global scale without listing on a stock exchange. Scottish Mortgage is a high profile trust whose managers embraced this and contributed very strong returns for shareholders.

Governments around the world increasingly accept market-led approaches to fund essential infrastructure and renewable energy; with a commensurate increase in funds being in a position to offer capital in these areas.

Finally, the GFC led to increased regulation in banks, and higher capital requirements limited their ability to lend. This offered an opportunity for non-bank lending which, given the fall in interest rates, saw a huge rise in interest from investors attracted to the income and lower risk investment characteristics.

Why might private assets make better investments?

For long term investors of all types, private assets make sense in a portfolio. ‘Diversification, the only free lunch in investing’ is widely attributed to the Nobel Prize winner Harry Markowitz, on whose work much institutional investing theory is based. Listed investments are arguably just an accident of history, so investors should examine the diversifying potential of other private assets.

There is a wide opportunity set, and the complexity and illiquidity involved in buying, managing and selling assets give good managers the potential to add significant value in less efficient markets. The opacity and expertise required to manage these assets means investment risks are potentially higher, but scale is also important, as many private assets have a ‘unit size’ of many millions of pounds, euros or dollars.

So how do non-institutional investors access these assets? In our view nothing can beat an investment trust, which provides an excellent structure to hold long term, illiquid assets.

‘Investment trusts provide an excellent structure to hold long term, illiquid assets’

In many areas, trusts already offer access to ready-made portfolios of private assets, which might otherwise take an institution (eg Calpers or Yale) months or even years to assemble – at significant cost.

As well as being able to ‘try before you buy’ – in analytical terms – investment trusts provide daily liquidity (admittedly of varying degrees) where otherwise there is none, at negligible cost and sometimes a material discount to NAV. Buying at discounts/premiums to NAV adds risk and opportunity, but for most investors without a multi-decade investment horizon, liquidity is a significant advantage that outweighs the disadvantage of a discount potentially widening significantly. An expert, independent board ensures the manager is performing their role correctly, reassuring non-experts in any asset class that their best interests will be looked after.

Private Equity

Private equity is investing in unlisted companies, arguably the most established ‘private’ asset class; we define three types of private equity investing:

- Buyouts– managers typically buy a controlling interest in a mature or semi-mature company, aiming to significantly grow its revenues and profits, often using significant debt financing, seeking a sale after three to five years. AIC Sector: Private Equity.

- Venture Capital– managers invest in early-stage companies, with explosive growth potential. They typically contribute to the founder’s growth strategy as well as capital markets expertise in terms of achieving an IPO in the future. There is no specific AIC Sector, but VC is included in some funds in the AIC Private Equity peer group.

- Growth capital– managers invest in pre-IPO opportunities, expecting the company will sell in the short to medium term. The strategy for each company will typically have been set, so investment is less about the input of the manager, and more about capital. AIC Sector: Growth Capital.

How well does the listed sub-sector represent the wider market?

The London listed private equity (LPE) sector differs from global private equity because of its historic focus on the UK and Europe, but many trusts are increasing their allocations to the US, the largest PE market by volume and deals. LPE trusts’ focus on buyouts echoes the wider market – in that buyouts have historically dominated private equity by AUM.

Buyouts typically add value through buy and build/consolidation routes, growth (expanding a niche, or growing internationally), and/or innovation. In our view, it is a repeatable process, and likely to have a higher ‘hit rate’ than say VC, which might expect some complete losses for every (big) winner.

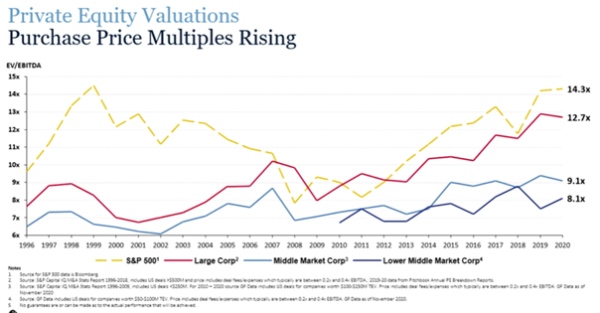

Buyout managers aim to buy companies at a low multiple, grow earnings and sell on an expanded multiple. That said, given the recent expansion of multiples, we heard in a recent NB Private Equity Partners (NBPE) webinar, that for many co-investment deal opportunities being priced up, private equity managers are often not factoring in multiple expansion on an exit, as part of a prospective deal.

NBPE’s 100% co-investment model differs from the rest of the LPE sector offering several advantages over peers including optimal diversification, as well as access to deal-flow and close control over the balance sheet/cash deployment enabling the team to respond to changes in market conditions in real-time. Additionally, shareholders pay only one layer of fees on most of NBPE’s co-investments.

This graph illustrates that there is a wide dispersion between mid-market valuations and large. Most managers represented by the LPE sector focus on mid-market deals, providing some reassurance to investors – particularly given that listed equities are trading on a significant premium to both. BMO Private Equity (BPET) is a fund of funds that invests with smaller, more nimble managers. They believe their approach means they will have more incentivised teams, and be more likely to be offered attractive co-investment opportunities, which are a key driver of returns.

Oakley Capital Investments (OCI), a directly investing PE trust, takes a slightly different approach, aiming to be the first institutional investor in a company. It supports management to grow revenue and earnings rapidly, and aims to ‘professionalise’ businesses, making them subsequent targets for other PE investors. The recent deal to sell (and reinvest in) TechInsights to CVC Growth Funds, is evidence this strategy is working.

What might investors expect from private equity returns

Private equity potentially offers the juiciest returns within the private assets universe, albeit with the highest risks. As per this article, Yale expects long term returns from buyouts ahead of listed equities, but less strong than those from VC.

We discuss the advantages listed funds offer in this article; we believe LPE trusts offer investors exposure to the same drivers of performance as institutional investors. NAV returns since the GFC have been strong; eg ICG Enterprise (ICGT) has delivered double digit returns each year since 2009 – in the five years to June 2021, annualised returns have been 21%, with total returns at a NAV level an impressive 16% pa. However, in periods of market stress, LPE trusts’ discounts have widened dramatically, making them suitable only for long term investors with tolerance for short term volatility.

2021 was exceptional for many trusts, but problems analysing the LPE sector comes from reporting time lags.

VC saw the strongest returns in 2021, helping trusts such as Harbourvest Global Private Equity which has 40% of its portfolio invested in dedicated VC/Growth equity funds. With interest rate expectations rising in the US (witness the fall in technology valuations this year), higher growth areas such as VC and the AIC’s Growth Equity sector (such as Chrysalis or Augmentum Fintech) might be expected to deliver muted short-term NAV returns. In contrast, buyout funds may offer less spectacular returns, but in a more consistent manner, because of the wider range of sectors and strategies employed by managers to deliver value.

Manager selection

There has historically been higher dispersion between the best and worst performing managers in the private space over time, meaning manager selection is critical; the GFC weeded out several LPE managers, and in the ensuing decade, several other trusts have been forced to wind-down. The current crop of surviving trusts might be seen as the ‘cream of the crop’. Discounts remain wide, and there have been few launches (Apax Global Alpha an exception), but fully research any trust before investing.

LPE fund of funds offer manager selection built-in; HVPE and Pantheon are large liquid trusts with very diverse underlying portfolios. They have both performed very strongly, albeit each has benefitted from a very strong year for VC; both have also benefitted from their underlying USD exposure.

Other fund of funds such as ICGT and BPET offer more targeted approaches, and make co-investments which results in more concentrated portfolios, albeit with several hundred underlying holdings.

‘The current crop of surviving trusts might be seen as the ‘cream of the crop’’

ICGT is differentiated by its access to ICG’s proprietary deal flow; it balances co-investments from ICG and third-party managers with a portfolio of funds. The team’s ‘secret sauce’ is blending access to the global network and wider ICG business (itself a direct investor in private companies) with the long history of the team behind ICGT as PE fund investors. The team targets a portfolio of c. 50% in conviction investments – which it actively selects – and 50% third party funds; it has delivered double digit returns for 13 straight years.

BPET targets smaller, niche, PE managers at an earlier stage in their management lifecycle; in turn, these managers target smaller underlying companies – in PE terms, the ‘lower mid-market’. BPET’s portfolio might be seen as a beneficiary of the record amounts of dry-powder (capital to be invested) amongst PE managers, an idea given credence as eight out of 12 exits to 08/’21 were to other private equity funds.

BMO believes that BPET is currently in a ‘sweet-spot’, selling investments into a competitive market, yet investing capital into an area of the market that is less competitive. Co-investments are a big part of the strategy – between a third and a half of NAV – representing the larger investments in the portfolio; as they mature they tend to dominate the top ten holdings – the ‘departure lounge’. Dotmatics, the biggest contributor to NAV in 2020 was a co-investment that made a gross return of 8.7x invested capital – an IRR of 83% p.a.

Single manager, or directly investing LPE trusts have more concentrated portfolios, so the success or failure of individual companies has a material impact on the NAV; they are likely to attract investors comfortable with the potential risks, taking a long-term view. HgCapital trust (HGT) is a specialist software investor; its specialism and track record mean that it has traded at a significant premium to both peers and NAV.

‘They will be well rewarded in having a material exposure to private equity trusts’

Similarly, OCI has a concentrated portfolio of growth companies in three sectors: technology, education and consumer; its total NAV return for 2021 was 35%. Its focus and expertise in specific sectors, its ability to source investments through a proprietary network of entrepreneurs and its discipline in terms of pricing and valuations make OCI highly differentiated from its peers. OCI trades on a discount to the published NAV of 22% (as at 27/01/2022), a big discount in absolute terms and likely relative to peers when they announce.

NBPT is unique in the LPE sector in offering pure exposure to co-investments (direct investments made alongside a range of third party PE managers); it’s very strong performance with NAV total returns of 40.7% showed the benefits of its approach. Final Q4 2021 private company figures should put it firmly on the listed private equity podium.

In our view, the portfolio’s maturity should give grounds for confidence for the years ahead, not to mention the types of companies and sectors that NBPE is currently exposed to.

Outlook

2021 was a banner year for private equity; NAV growth has been impressive, which – alongside the general interest in private markets – should rightly draw attention to the LPE sector. Currently, with NAVs incorporating underlying valuations from many different dates, it is hard to definitively comment on the level of discounts. Irrespective, for long term investors, prospective NAV growth should be the main area of focus.

In our view, the fact that private equity managers are forced to take the long-term view is a key factor in their historically having delivered so handsomely for investors. The future is always unclear, and perhaps never more so currently. However, for long term investors we continue to believe they will be well rewarded in having a material exposure to private equity trusts. The LPE sector has plenty to choose from.

Disclaimer

This is not substantive investment research or a research recommendation, as it does not constitute substantive research or analysis. This material should be considered as general market commentary.

Alternative investments Commentary » Alternative investments Latest » Commentary » Equities Commentary » Investment trusts Commentary » Investment trusts Latest » Mutual funds Commentary

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.