Sep

2023

UK, OK, Hun?

DIY Investor

1 September 2023

Sentiment towards the UK is at rock bottom, which means only one thing…by Thomas McMahon

Britain is a country where the serious press will straight line recent economic growth in Poland for the next 20 years, compare it to straight-lined UK growth and decide Poland will be richer than the UK imminently.

Commentators will then do colour pieces based on their walks around Bydgoszcz in their leather jackets reporting how you can just feel how Poland is richer, even though the numbers they are discussing are a projection of the state of affairs 20 years’ hence and current numbers show the UK is still much richer (over twice as rich, in fact).

Somehow this is all related to the inability of a journalist to buy a five-bedroom house in zone 1. On the right, Britain’s commentators like to claim the poorest states of the US such as Mississippi are richer than the UK, which is an interesting take. Arguably, Britain needs a psychiatrist, not an economist.

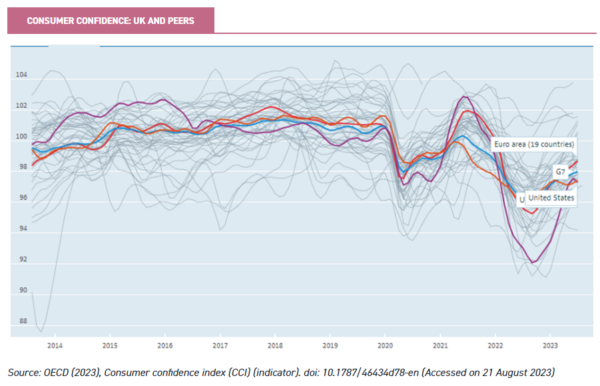

I think this addiction to doom, whether it be rooted in our national character, a symptom of political polarisation post-B**** or something else, explains in part the consensus view that the UK economy is cream-crackered. I expect it has contributed to the extreme gyrations in the consumer confidence index for the UK (the purple line) visible in the chart below.

Now, you can make a case that Britain is more exposed to global prices than the US, so as global inflation moves it could be perceived as more of a threat to the UK, and you can point out the UK had a full national lockdown during the pandemic unlike the US, which may have led UK consumer confidence to move more dynamically.

But similar points could be made about a number of countries that didn’t report such an alarming decline in consumer confidence. The pace and magnitude of both the drop and the rebound in the UK numbers are striking. Those countries which saw consumer confidence hit lower lows than the UK?

Latvia and Estonia, both of which faced the possibility of literal military invasion, and Turkey, which borders not one but two warzones and has seen its currency collapse amidst political instability.

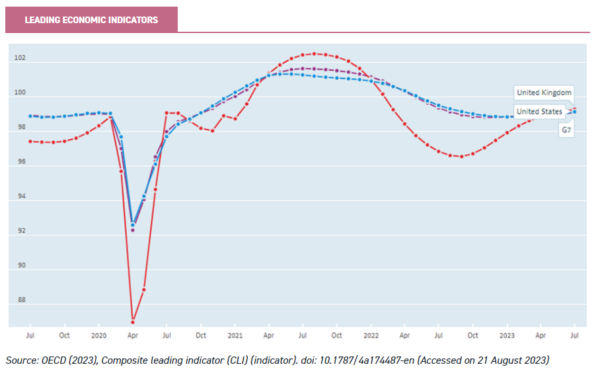

The extremity of the moves can be questioned, but the direction of travel is rational. I think it is now starting to be acknowledged widely that the outlook for the UK has improved, and this is indeed visible in the OECD’s leading indicator series below. To be clear, all these numbers are below 100, so they represent expectations of a marginal slowing of economic activity. But nothing like what was expected six months ago, and it is worth noting that the dramatic drop in activity previously anticipated did not emerge.

Quietly the news seems to be dribbling out that the UK is actually doing OK. We have not experienced the “mortgage timebomb” we were “facing”, unemployment remains at extreme lows, and lower than France, Germany or the US, while the UK economy has grown in 2023, unlike that of Germany or the Netherlands, which are in recession. Indeed, neither the polemicists of left nor right see it in their interests to reflect on the fact that a key reason inflation has remained a little higher in the UK than on the continent is precisely because our economy is a little stronger and domestic demand is a little higher. Another key factor, of course, is exactly how and to what extent energy prices have been subsidised – i.e. a technical factor that makes the hand-wringing about differences in month-on-month readings between countries asinine – but great copy if your business model is making money out of whipping up anxiety.

None of this is meant to imply a new golden age is beginning. Britain’s economy is facing headwinds, as are those of our peers. While we are not in recession, growth remains extremely weak and higher interest rates are likely to continue to have delayed effects as time goes on. The consumer’s willingness to spend and borrow will likely decline, more and more businesses will have to regear, and house prices will likely be weak, repressing all the economic activity associated with moving home. The slowdown in China will also impact UK firms – although it will also reduce pricing pressure on commodities which will dampen inflation. However, I think investors have a distorted view of how serious these issues are and how major their impacts will be.

This is not just a UK-wide issue. In the US too, investors seem to have assumed rising interest rates would have more of an impact than they have. One indicator comes from US data showing that the net interest payments of non-financial corporations have actually fallen over the past year. Why would this be the case? Presumably, this reflects the maturing of older, more expensive debt in preference for debt issued before the recent hiking cycle, as well as de-gearing efforts by companies anticipating a hiking cycle. Some of this balance sheet management may reflect action taken during the pandemic to build resilience. In any case, the US economy has proven much more resilient to rate hikes than expected, and this seems a key piece of explanatory data.

The Bank of England (BoE) doesn’t enjoy access to information anywhere near as good as this on the UK economy. Last week, it published widely quoted research which warned of the potential for defaults as rates remained high. But digging into the report it is clear they had to use balance sheet data from 2021 for most companies, as this was the most recent data available. They then calculated the notional impact of the rate hikes experienced since and those still expected on those out-of-date numbers. Is it possible that UK companies have also substantially improved their resilience over the last two years, as American companies have, and so the impact of rate hikes will be lower than expected? It’s hard to believe they haven’t. (As an aside, it’s worth remembering how tough the BoE’s job is. They are slated whatever they do, and no doubt they don’t always get it right, but what hope do they have of anticipating how their actions will affect the economy with data this out of date?) Companies having more resilience to higher rates than expected would be a potential explanation for why the BoE has expected inflation to be lower than it has been and has had to raise rates much higher than it initially thought.

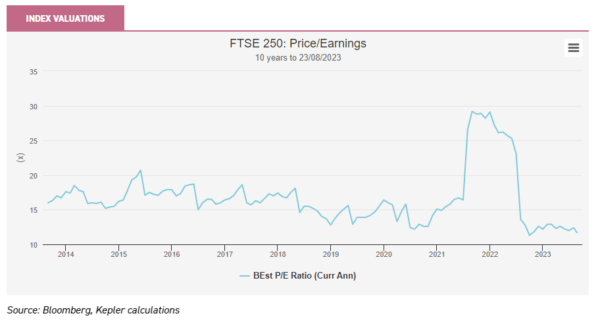

For investors, the question is what is priced in? Is it the moderate slowdown that data is suggesting in the price, or is it the dramatic catastrophe implied by the headlines and the consumer sentiment readings of a few months ago? At the index level, valuations look pretty extreme. The P/E ratio of the FTSE 250 is well below its ten-year average, according to Bloomberg. In fact, the only time it has been lower since the financial crisis was during the nadir of the pandemic when the economy was facing enforced closure for an indeterminate amount of time. In other words, market pricing implies the outlook is as poor as it was during lockdown or during the aftermath of the collapse of Lehman Brothers. This seems unwarranted.

In the investment trust space, investors are getting a discount even on these extreme levels of valuation. Focussing on the mid caps, high-quality trusts Mercantile (MRC), JPMorgan Mid Cap (JMF) and Schroder UK Mid Cap (SCP) are all available on a discount of c. 13-14%. All three have excellent track records of adding value with different strategies. An additional factor to consider is that while the FTSE 250 is considered a proxy for the UK domestic economy, revenues are fairly equally split between the UK and overseas. This idea that the FTSE 250 is domestic and the FTSE 100 is foreign is widely held, but it is a distortion of a much more balanced picture. And this is at the index level, on the stock-specific level many companies are simply not reliant on the health of the UK economy to grow. In my view the extreme negativity towards the UK is being indiscriminately applied to UK-located assets, whether they are dependent on UK plc or not, and over time investors will pick up on this.

Indeed there is some evidence that extreme value is already beginning to be recognised. I think it is fair to say US real estate investors are at the ruthless end of the spectrum and are unlikely to be investing in the UK out of a sentimental wish for dear old Blighty to do well. I think the purchase of Industrials REIT by Blackstone, and the advanced talks between Realty Income Corporation and the board of Ediston Property Income are straws in the wind. Managers we talk to expect takeovers of undervalued UK companies to pick up across a variety of sectors. In my view, it’s easy to get caught up on the risks of investing over the next few months, but looking at valuations and sentiment they seem to be at long-term bottoms. It’s worth considering that when sentiment is poorest the reason for a potential re-rating is never clear – otherwise sentiment would be better. But investing at these times tends to be when the best gains are made, and waiting for the way out to become clear often leads to missing out.

Disclaimer

This is not substantive investment research or a research recommendation, as it does not constitute substantive research or analysis. This material should be considered as general market commentary.

Brokers Latest » Equities » Equities Commentary » Equities Latest » Investment trusts Commentary » Investment trusts Latest » Latest

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.