Mar

2023

The next supercycle

DIY Investor

12 March 2023

Our research suggests a structural tailwind could support the prospect for commodities throughout the next decade…by William Heathcoat Amory

Rather like investing in Japan, anyone who has been investing in equities for more than a few years has been burnt at least once by an exposure to commodities. On the other hand, those who time their investment correctly may make bumper returns.

Like a moth to a flame, commodities have an enduring attraction, precisely because they are so cyclical. So, following on from two strong years, is it too late to join the party? Our research suggests that, over the next decade, several factors have coalesced to form a structurally positive scenario which may lay the foundations of what might, in time, justifiably be described as a new supercycle.

Commodity markets, and equities exposed to them, have a tendency to exhibit strong cycles, with booms inevitably setting up busts, which themselves form the foundations for future recoveries. The commodity sector tends to exhibit cycles with more vigour than most sectors and the resulting volatility tends to result in reticence for those burnt last time to be sucked in next time, perhaps exacerbating the volatility further with investment flows reaching their peak as the cycle matures.

At the same time, commodity markets tend to exhibit their own cycles, sometimes seemingly independent of the global economy or other equity sectors and, for many, this is part of the attraction. The table below illustrates this point. The S&P GSCI Index is one of the best-known investible commodity indices. It is, according to S&P, “broad-based and production-weighted to represent the global commodity beta” and, therefore, approximates a basket of global commodities.

We also include indices representing global mining companies and energy companies, as well as the MSCI All-Country World Index. Readily appreciable is the fact that mining and energy companies tend to exacerbate the volatility of the S&P GSCI Index, but sometimes offer very different returns.

2014 and 2015 represented one of the most recent and savage periods for commodity-related equities, such as miners. As we will come to later, they are recent enough in the corporate memory to still influence the behaviour of senior management of these companies. 2020 held its own unique challenges, but as the table below shows, 2021 and 2022 were very strong periods for commodity markets. Compared to other asset classes, there are few areas that delivered such strong returns in both years, which we observe were almost opposites, in terms of broad equity market conditions.

GBP total returns

| 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | |

| S&P GSCI | -3.1 | -28.9 | -29.0 | 32.8 | -3.4 | -8.5 | 13.1 | -26.1 | 41.6 | 41.9 |

| EMIX Global Mining | -24.1 | -13.0 | -36.9 | 94.0 | 20.8 | -5.8 | 22.7 | 25.8 | 11.0 | 17.2 |

| MSCI World/Energy | 15.9 | -6.1 | -18.3 | 51.0 | -4.1 | -10.6 | 7.1 | -33.6 | 41.4 | 64.4 |

| MSCI ACWI | 20.5 | 10.6 | 3.3 | 28.7 | 13.2 | -3.8 | 21.7 | 12.7 | 19.6 | -8.1 |

Source: Morningstar

Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future results

After such a strong couple of years for commodities, it is perhaps unsurprising that investors may be wary of the space. After such a strong couple of years for commodities, it is perhaps unsurprising that investors may be wary of the space. However, having taken a look at the specific and unique set of circumstances that the global economy finds itself in, in 2023, it would appear that whilst there are clearly short-term cyclical risks, the long-term prospects for a secular upswing for commodities appears strong.

Each cycle is different and this one is certainly so

As we note above, the commodities and resources sectors are inherently cyclical. Fundamentally, this is because of the relatively inelastic supply curve of oil production and mines to changes in price. It takes a long time to prospect, permit and build new extraction. This means that changes to demand can quickly impact the prices of commodities and these changes can remain for quite some period.

As we illustrate in the table above, the equity of resource stocks can exacerbate this volatility, given that equities reflect expectations of commodity prices and margins for many years into the future. The negative commodity markets in 2014 and 2015 took many very large mining companies near the edge. Companies had expanded production and borrowed heavily. Subsequent declines in commodity prices led to many companies finding themselves overextended and having to slash dividends and capex to pay interest or refinance debt.

It proved a formative period for the mining sector and, since then, company managements have remained focussed on more disciplined capital allocation, deleveraging balance sheets and paying dividends in line with cashflows, rather than aiming for progressive increases.

Despite these moves, many investors fled the mining sector following such a self-induced and woeful period of performance. At the same time, the global mega-cap technology sector absorbed many investors’ interest, being the gift that never stopped giving – until 2022. At the same time, the rise of ESG in importance for many investors around the world meant that many managers more easily forgot the sector entirely.

2020 proved to be another heart-stop moment for commodities, but particularly for energy companies. Big oil was, historically, an income stalwart in many portfolios. When Covid restrictions meant an unprecedented reduction in economic activity, energy prices around the world crashed and oil companies announced cancelled, or significantly cut, dividends in a bid to ride the downturn.

For many equity income funds, this disappointment and the uncertainty about the immediate future prompted a wave of selling of energy-related holdings. The rise of ESG-investing likely contributed to the sector being avoided and, running up to the end of 2020, oil companies were trading at historically low ratings.

It is important to note that share prices in both the mining and energy sectors are an important consideration for company management when determining new projects and capital expenditure. In evaluating prospective projects, the management team must weigh the potential returns of new projects against buying the company’s own stock back.

Fundamentally, if a company’s share price rating is low, then the prospective returns on capex need to be higher in order to make them an attractive avenue for investing the company’s capital. This is particularly so now that more long-term management incentive schemes are, rightly in our view, skewed more towards long-term shareholder returns, rather than growth for growth’s sake.

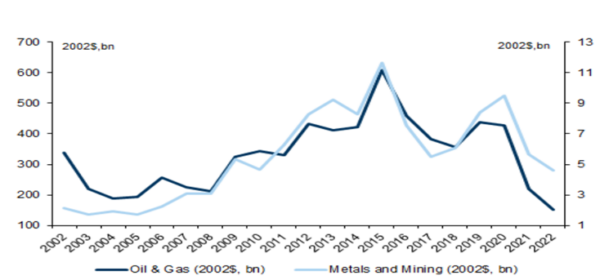

The near-extinction event that many mining companies experienced in 2015, a near decade-long buyers’ strike by institutional investors and the economic worries presaged by Covid, provides the context behind the currently constrained supply picture in many commodities, both for energy and metals. Company management have had every reason to say no to prospective projects, and relatively few to say yes. The graph below illustrates that capex continues to decline since the 2016 peak.

The same conditions exist going into 2023, if not more so. With high energy prices for miners, high inflation and high interest rates, it will require even more attractive returns from prospective projects to beat buybacks, for companies looking to invest capital. From the supply side then, conditions do not appear to be shifting away from a broad picture of increasingly constrained production. This means that any sustained increase in demand should have a significant impact on prices, setting the scene for a longer-term secular upswing in the fortunes of the sector.

Oil & gas/metals & mining (RHS): Real capex in 2002 dollars

Dr Copper: a finger on three pulses

The Russian invasion of Ukraine serves as a useful and painful reminder of how sudden shifts in market dynamics can have outsized impacts on prices of globally-traded commodities, especially where supply is constrained. Oil price shocks are not new.

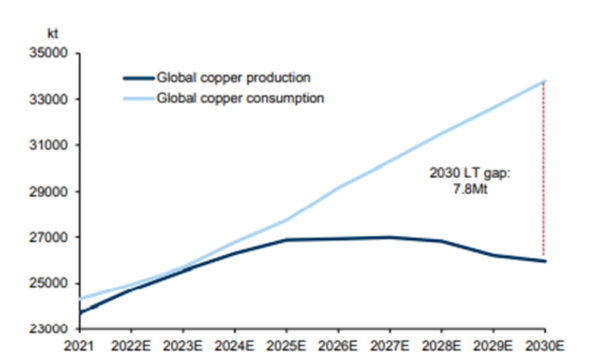

Within the metals and mining sector, many analysts focus on copper. The best and most productive copper resources are steadily being used up, leaving only harder-to-access deposits in the more far-flung corners of the world. According to many analysts, the market is becoming increasingly tight. However, despite the relatively strong price, capex starvation since 2015 is having its effect.

According to Goldman Sachs, a breadth of issues at mines across the continent of South America means that production for 2023 is expected to come in significantly behind expectations. Operators are citing cuts to maintenance capex as the key factor in the disruption leading to underperformance.

This production shortfall is, therefore, self-inflicted and is an inflationary tailwind for short-term copper prices. The Vale tailings dam disaster of January 2019 serves to illustrate another persistent inflationary force, with safety and regulatory considerations ratcheting tighter every year, making production hikes yet harder to achieve.

Set against this relatively inflexible supply is the potential multi decade-long investment in renewable energy generation capacity around the globe, a significant incremental source of copper demand. Governmental initiatives, such as RePowerEU and the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), have materially ramped up the trajectory of renewables’ build-out around the world.

Two new significant sources of demand, geographically spread, is likely a significant development for copper in terms of the long-term demand picture. Perhaps most importantly is the fact that with three economic blocs, i.e. China, US and Europe, competing for copper to underpin a long-term competitive advantage with abundant carbon-free energy, the price is arguably likely to be less volatile than in the past.

Historically, the main determinant of copper demand was Chinese construction activity, itself relatively cyclical. With China reopening after Covid into a stuttering global economy, the immediate outcome is far from predictable, from a copper demand perspective. However, Goldman Sachs believe that the green structural rise in demand will “near outweigh the cyclical slowdown…expect[sic] c. 2% growth in copper and aluminium demand compared to a contraction in prior recessions”. Goldman Sachs illustrate, in the graph below, the huge gap in supply and demand that they envisage appearing from 2024 onwards.

Goldman Sachs estimates of copper supply/demand

Cost of carry

2022 marked a sea change in macroeconomic conditions. The US dollar strengthened, itself a dampener on demand for commodities around the world, which tend to be priced in dollars. At the same time, interest rates have risen around the world and inflation has impacted almost every aspect of commodity production on the cost side.

Taken together, these are all inflationary forces for commodity prices. Higher interest rates have an important effect of increasing the cost of holding inventory by producers, traders and other market participants. According to BlackRock, at the end of 2022, inventories at London Metal Exchange warehouses were at 25-year lows.

Available inventories of aluminium, copper, nickel and zinc decreased by over two thirds during the year. It is possible that across the industry, some of the supply constraints have been masked by destocking. As the sector sheds inventory and becomes less capital-intensive, it is possible that supply constraints will start to influence prices faster and more impactfully.

Certainly, now that a deep global economic recession appears less likely, with a much-reduced inventory and a hobbled supply, any improvements in global demand for commodities may start to be felt quicker.

Diversification

Investors may be attracted to the fundamentals of commodities. However, from a portfolio perspective, commodities have powerful attractions for their diversifying properties. Aside from commodities’ relatively direct link to inflation, commodities may prove a useful hedge in investor portfolios due to their inherent exposure to the USD.

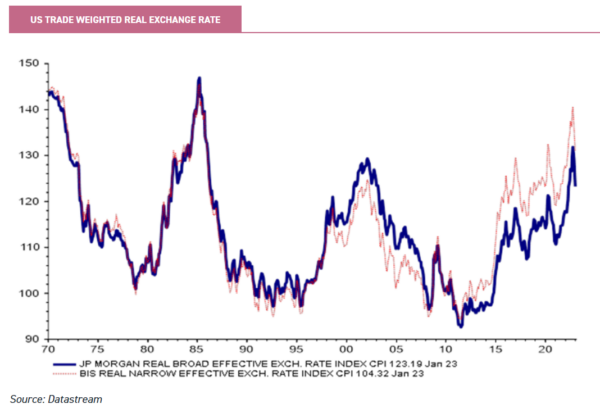

We observe that the USD is structurally very expensive (see graph below) on a real exchange rate basis and is at level not seen since the year 2000. As the graph below suggests, real exchange rates not only tend to revert to mean over the medium to long term, but can also overshoot very significantly at times. This presents real risks to global equities’ portfolios.

The MSCI World Index has a significant inherent bias to the USD, given that US equities represent a massive 68% of the global equity benchmark, as at 31/01/2023. Commodities tend to trade inversely to the US dollar, meaning that if we are entering a long-term period of USD weakness, they may be an interesting way to offset this risk.

Other ways to benefit

A knock-on effect of strong commodity prices and a weak dollar is that, usually, EM equities perform strongly in this scenario. Ironically, even commodity-importing countries, like India, have stockmarkets which typically correlate positively with commodity prices.

And for resource-producing countries in particular, a commodity upswing can often result in domestically-orientated companies in those economies performing very strongly. These companies are often better run and are less volatile than the resource companies themselves, but yet still benefit from the macro tailwinds of a strong currency and strong domestic growth.

South America, as a continent, is under-represented in EM indices and funds, yet its economies are likely to be clear beneficiaries of stronger commodity prices, especially if the USD is in a weakening phase. Within the investment trust universe, there are two trusts that offer a pure exposure to the region.

BlackRock Latin America (BRLA) is managed by Sam Vecht and Christoph Brinkmann. They argue that the region has a positive outlook for 2023, with Brazil likely to be in a position to cut rates later in the year, having taken its medicine early. While they were cautious on commodities in the short term at the start of the year, in keeping with a widely-held view that economic growth may disappoint globally, the portfolio still has a significant direct exposure.

The top holding is the Brazilian miner, Vale. Moreover, the indirect exposure is notable, with the consumption and financials stocks in the portfolio likely to do well from any wealth effect stemming from buoyant commodity prices.

abrdn Latin American Income (ALAI) invests in a mixture of equities and bonds in the region, in pursuit of yield, as well as growth. The style bias of the equity portfolio is towards quality growth, and it is typically underweight commodities. This means that the companies that are picked should be those with greater pricing power and more stable and secure finances.

These are potentially attractive features in an inflationary environment. In our recent meeting, the managers argued that, in general, companies in the region are more used to dealing with this sort of environment (and with political volatility) than those in the UK or its developed world peers. We have published a new note on the trust this week. Both ALAI and BRLA have performed well over the past two years, thanks to the commodity exposure in the region.

Conclusion

The past two years have been humbling for most investors. Growth stocks continued to roar through 2021 before being humbled in 2022, whilst value continued to be ignored over 2021 and then, in 2022, had revenge by trouncing growth. Throughout these two very different periods, commodity and mining-related trusts have performed well, illustrating their strong diversification benefits.

As we have discussed above, whilst there is a short-term impact of a global economic slowdown or recession on commodity prices, the longer-term secular growth picture looks underpinned by a structural increase in global demand, faced with little capacity for the industry to ramp up supply. Aside from the potential for attractive multi-year returns, the diversification properties of commodities are also likely to prove highly attractive for owners of global portfolios.

This is a specialist area of investment and, with commodity-related stocks such as energy and mining companies being so different to other sectors, in our view it makes absolute sense to hire a sector specialist.

BlackRock World Mining (BRWM) can be seen as a virtual mining company, with flexibility to quickly shift allocations between commodities, depending on the managers’ view at the time. This is unlike a standalone mining company, which needs to invest significant capex and resources, not to mention time, to execute a strategy.

BRWM is managed in a high-conviction manner, which results in a relatively concentrated portfolio, and its short-term volatility will generally be higher than the wider equity market. However, we believe BRWM is a compelling proposition for investors aligning their portfolios to the long-term opportunities we identify above. It also has a strong appeal to investors seeking income. We published an analysis of BRWM’s most recent results this week, available here.

Sister trust BlackRock Energy and Resources Income (BERI) is managed by different individuals to BRWM but within the same team, and provides a slightly different, but no less, interesting exposure. We have updated our research on the trust this week, available here.

The trust shifted its strategy in June 2020, explicitly positioning the portfolio towards decarbonising the global economy. However, the trust is managed by a team with their feet anchored firmly on the ground, with a practical and real-world understanding of what the transition towards net zero is likely to look like.

Allocations are expected to move dynamically between mining, traditional energy and energy transition stocks. As a result of decisive positioning by the team, BERI’s performance has been driven by its significant exposure to traditional energy companies, which have been reporting bumper profits. Whilst not exactly what one might have expected when the board evolved the strategy, we think it shows the benefit of having sector specialists at the helm, who have an appreciation of the fundamentals.

Disclaimer

This is not substantive investment research or a research recommendation, as it does not constitute substantive research or analysis. This material should be considered as general market commentary.

Alternative investments Commentary » Alternative investments Latest » Brokers Commentary » Commentary » Investment trusts Commentary » Investment trusts Latest » Latest » Mutual funds Commentary

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.