Mar

2023

The Devil’s in the demographics

DIY Investor

6 March 2023

China’s population is in decline – should it turn east or west for inspiration..? by Ryan Lightfoot-Aminoff

In January of this year, China hit a key milestone that has significant implications for the country and the world – its population fell. Official statistics noted a drop of 850,000 people in 2022, an equivalent population to the city of Liverpool. When put in the context of the 1.4 billion+ population, this amount seems small, but the trend has big consequences.

In our view, the way Chinese authorities are tackling this challenge will increasingly mean that Chinese companies need to be considered alongside their Japanese and European equivalents as competitors and peers, rather than as growth outliers. In fact, we think Japan and Europe may house companies with more exciting earnings growth potential than China, now the demographic boom is over.

Demographic decline

The key issue for China’s worsening demographics is that this is almost certainly the beginning of a new trend. A combination of rapid economic growth and government policy has led to a decline in the birth rate in the country.

This has persisted for years and has now had an impact on the aggregate numbers. With little to support an uplift in births, the UN’s median forecast for China’s population by the end of the century is to be almost half of today’s figure.

The potential implications for investors are huge. A falling population will mean a shrinking and ageing workforce. For China itself, this will have a number of associated social issues that it will need to address. For the world, there are huge economic consequences.

China’s large, low-cost workforce has been one of the biggest driving forces of the world economy in the past few decades and one of the key factors behind globalisation. The country has taken advantage of this human resource to become the world’s warehouse and be at the centre of cheap manufacturing for developed economies.

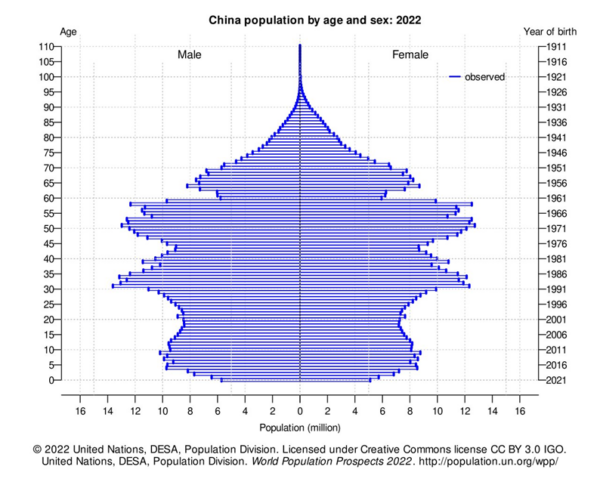

China’s population pyramid (see below) shows this starkly, with the largest cohort currently between 30 and 60 years old and the younger population, below this, considerably fewer in number. In less than a decade, more of China’s population will no longer be of working age and be economic detractors, rather than contributors.

China’s population distribution

Source: United Nations

This has consequences for companies in terms of demand for their products and the availability of labour. Additionally, as the country develops, wages are creeping up. One positive outcome of the economic growth is the boom in the middle classes in China. Large swathes of the population have been dragged out of poverty and now have aspirational lifestyles and salary demands have picked up because of this.

As a result, the country is starting to lose its edge as the straightforward choice for low-cost manufacturing. Competitors, in the likes of India and Vietnam, have similar or better demographics than China did 20 years ago and are using this to challenge the low-cost manufacturing base China currently houses, and attract foreign investment. China, on the other hand, has seen a souring of its international relations as its growth has become a threat to established world powers. As a result, China is seeing its edge in lower-cost manufacturing being competed with and chipped away, as the table below illustrates.

Chinese wages vs global peers

In response, the Chinese government has made a number of policy changes. Firstly, to address the birth rate issue head on, they have relaxed the one-child policy, first in 2015 and again in 2021, although early signs are that this has had limited success. Secondly, there have been a number of economic reforms under the guise of ‘common prosperity’.

The government has enacted policies to restrict profit making in private education and limited the time allowed on online gaming, as two key examples. Their goal is to broaden the growth in the country and create efficiencies to make their industries and workers more competitive, globally. However, these have been seen as anti-capitalist by investors and have led to a considerable sell-off in 2022. Many investors remain wary, knowing that government intervention could well wipe out entire industries overnight.

As a result of these policies, a declining working age population and a maturing manufacturing sector, China has become less competitive on the global stage from the manufacturing base that has driven its growth for much of the past few decades. In response, economic activity has shifted higher up the manufacturing value chain, and this has put Chinese business in direct competition with two other major stock markets – Europe and Japan. In our view, they will be increasingly competing globally in higher-end products, without the advantages of much lower wages and a growing domestic market to tap into.

European glamour or Japanification clamour

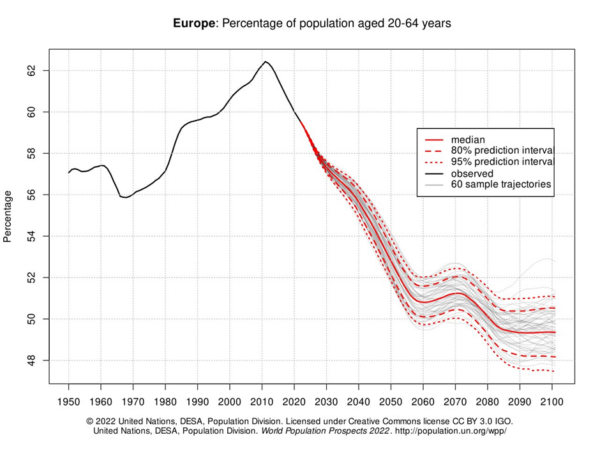

Europe is also struggling because of a declining working age population, with the percentage of 20 to 64 year olds having peaked around a decade ago, and expected to drop to only half of the total population by 2060. This presages the struggles China is likely to encounter in the coming years.

Europe’s working age population

However, whilst Europe’s wealthy, ageing population remains a headwind to earnings growth due to higher wages and a lower number of workers, there remain plenty of companies which are able to succeed due to their focus on ‘premiumisation’.

Europe moved away from low-cost manufacturing many years ago, instead, outsourcing this to the likes of China. However, the region remains a manufacturing and business powerhouse, with a large number of high-end goods and services companies which continue to be world leaders and deliver sustainable earnings growth.

ASML is an example of this. It is the leader in supplying critical machinery required for the semiconductor industry. Without them, most of the world’s chips would not be able to be manufactured and the technology sector would be years behind where it is, currently. The business has excellent pricing power, higher barriers to entry and resilient growth. LVMH is a similar example.

It is a multinational luxury goods company which holds some of the world’s leading brands, from fashion to premium drinks, ranging from Louis Vuitton to Dom Perignon. These brands have heritage and strong recognition, which is hard to replicate. As such, they have developed huge desirability, leading to them becoming industry leaders in a range of markets, particularly China.

Both companies are top ten holdings for Blackrock Greater Europe (BRGE) and JPMorgan European Growth & Income (JEGI). For BRGE, manager Stefan Gries focusses on these high-quality, high-growth companies when building this trust. He has a long-term focus, meaning that when these ideas are found they are given time to run, which we believe offers a highly attractive way to gain exposure to the growth prospects of the continent.

Whilst the market is currently being weighed down by sustained interest rate rises, we believe the market may reward this approach more, as the ability to deliver a return above the cost of capital is increasingly valuable. JEGI has been recently formed from the merger of the JPMorgan European Growth (JETG) and JPMorgan European Income (JETI) portfolios and offers a combination of core European exposure with an attractive dividend.

The three-strong management team of Alexander Fitzalan Howard, Zenah Shuhaiber and Timothy Lewis look to answer four simple questions when considering a company: is it a good business, is the stock attractively valued, is the outlook improving and is the business sustainable? This leads to a portfolio offering a ‘one-stop shop’ for the opportunities within European equities and for capturing the growth the region’s companies offer, despite the region’s demographic headwinds.

The fears over Japan’s demographic time bomb have been known for decades. It is one of the world’s oldest societies and has seen population declines since around the turn of the century. The country built its wealth on a successful manufacturing sector, so could provide a model for China to follow. The country has improved productivity to support its economic growth.

This has led to the emergence of a number of globally leading industries in the country, such as automation and robotics, with companies such as Keyence a prime example. They are a global leader in robotics, amongst other things creating the manufacturing sensors, which are used in factory automation. It helps make production lines more efficient, which has helped Japanese industry, and their products are shipped to over 30 countries globally, including the US, UK and Germany. It is the top holding of JPMorgan Japanese (JFJ).

JFJ can invest across the market-cap spectrum to identify Japan’s best secular growth opportunities. These are typified by the ‘New Japan’ industries, such as automation and robotics, and can include the younger, more dynamic companies the country has to offer.

Manager Nick Weindling argues that investors often mistakenly focus on the macro situation in Japan, such as the demographics, rather than appreciating the strong earnings growth generated by Japan’s world-leading companies – EPS on the Topix has actually grown faster than that on the S&P 500 since 2010, boosted by innovative, highly-productive companies such as Keyence. We have published an updated note on the trust this week.

Schroder Japan Growth (SJG) is another trust that has exposure to the automation trend. In their last financial year, they initiated a position in Yokogawa Electric, which specialises in measurement and control equipment. Manager Masaki Taketsume also believes there is long-term growth potential within the subsector. He has a stock-selection approach to building the trust, aiming to identify attractively valued, growing companies by exploiting the depths of the under-researched Japanese market.

China’s challenges

These companies are just a small sample of the type of competitor Chinese peers are going to start coming up against, should they look to move up the value chain and premiumise their industrial sector. Semiconductors and robotics are, undoubtedly, growth opportunities and capturing these could provide a partial solution to their demographic problems.

One obvious conclusion, though, is that these existing leaders could be the better way of playing the potential Chinese growth story. The likes of Keyence and Yokogawa are going to be critical suppliers to China, in order to enable their automation industry to flourish. Building a domestic competitor from scratch will be expensive and time consuming and, whilst this wouldn’t be a surprise in the context of China’s rapid growth up to now, these companies are specialist and highly advanced.

This is, perhaps, a reason why the Chinese government is looking at other domestic opportunities to refocus their economy. The healthcare sector is an obvious area that will see an increase in demand. The government is primarily motivated to develop it because of the demographic issues, but it is a sector that is also requires a high level of skill and can offer almost unlimited high-end growth, meaning there is also considerable reward available.

The development of successful drugs, for example, will be patented, leading to a guaranteed revenue stream for years. The ability to export potential vaccines or treatments around the world could be hugely profitable for China and provide the double benefit of sustaining growth, as well as health benefits, to its ageing population.

There has been considerable private investment into the area, especially since the pandemic, which brought the importance of healthcare investing sharply into focus. Healthcare investment from venture capital and private equity deals in China totalled $31 billion in 2021, and $16 billion from the start of 2022 to September, according to figures from Reuters.

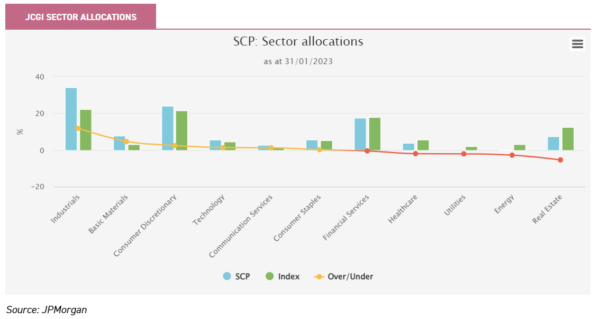

It is a sector that JPMorgan China Growth & Income (JCGI) is overweight. The three managers, Howard Wang, Rebecca Jiang and Shumin Huang, believe that the ageing society and rising wealth levels will lead to investment opportunities in the area. They are looking for the premium opportunities within the country and have a focus on the industries China needs to invest in, in order to continue its growth. These include the aforementioned automation and robotics industries, which the managers believe will play a big part in the upgrading of the country’s industrial sector.

JCGI sector allocations

With these areas of focus, the government is looking to create a more efficient manufacturing sector and produce higher-end products, rather than the low-cost, low-margin goods of the past. They are also looking to broaden the sectors where growth is coming from and create efficiencies within them. The goal of this is to offset the impact of poor demographics and rising wages on their economic advantage.

So, while demographics are undoubtedly a problem for China, it is clearly something the authorities are aware of. When we spoke to the team behind Invesco Asia (IAT) recently, they highlighted the rapid policy changes the government has made in recent years. The one-child policy lasted for 25 years before being changed twice in six years and, ultimately, removed. And while it is an issue, the team believe it is just one of a number of issues China faces, including geopolitical tensions and increased competition. However, they have highlighted that challenges tend to lead to innovation and this is something the authorities remain heavily focussed on.

As at 31/12/2022, China was the largest country weight in IAT´s portfolio. The trust continues to take a selective approach to the country, knowing the issues it faces, but the managers have still managed to find a number of good value opportunities. One of the managers’ largest holdings is Ping An Insurance, which is a leader in life insurance, an industry which could be expected to be a winner due to the demographic changes. Recently, the company has also branched out into the healthcare space, which offers a further growth opportunity for the company.

Conclusion

The drivers of the Chinese growth miracle of the past may well be behind the country, and the China of the future is going to need to find other drivers. In our view, this will drag the country’s companies into direct competition with European and Japanese peers, which is going to be a tough battle. European and Japanese companies are well-established with proven business models, difficult to replicate intellectual property and have less chance of political interference. Despite this, China, and Chinese companies, will remain very integrated with the global economy and while its role may change, the country will continue to throw up opportunities. Ultimately, we think China’s falling population is a risk to old investment strategies and requires a rethink. The days of Chinese companies being the growth outliers may well be behind them.

Disclaimer

This is not substantive investment research or a research recommendation, as it does not constitute substantive research or analysis. This material should be considered as general market commentary.

Brokers Latest » Commentary » Investment trusts Commentary » Investment trusts Latest » Latest » Mutual funds Commentary

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.