Oct

2021

Slings and arrows

DIY Investor

17 October 2021

This is not substantive investment research or a research recommendation, as it does not constitute substantive research or analysis. This material should be considered as general market commentary.

Our analysts argue over whether it’s better to take arms against volatility in a portfolio, or to simply suffer it…

Our analysts argue over whether it’s better to take arms against volatility in a portfolio, or to simply suffer it…

It is fair to say the last 18 months have been a wild ride for markets – and life has been pretty volatile outside of them too. It is notable how the volatility of indices as well as individual trusts’ NAVs and share prices have been higher over the past 18 months than they were before.

As we discussed in a recent strategy note, the best performer through the pandemic period was the mighty Scottish Mortgage (SMT), despite at least one significant drawdown during the period and the highest NAV volatility in its sector.

This leads us to ponder whether there is a lesson in this. Should investors look for managers and trusts that can keep volatility low, or should they focus exclusively on returns and accept volatility as a consequence? Our analysts examine the case for and against keeping volatility low

Are your eyes bigger than your stomach? – John Dowie

As we have all seen and experienced, stock markets have cycles of booms and busts. Investors with the intestinal fortitude to buy stocks cheaply when others are panicking, such as in March 2020 during the initial pandemic outbreak, set themselves up to gain handsomely.

Conversely fair-weather investors who chase performance, buy stocks at high prices but cannot really tolerate volatility end up selling low and realising losses. Of course, these two phenomena are different sides of the same coin: the savvy buyers need naïve sellers and vice versa. To borrow some poker terms, in markets there are sharks and there are suckers.

This is where I would respectfully point out the weakness in the idea that volatility should just be accepted, and eyes firmly fixed on the long-term rewards. One of the biases studied in behavioural finance is something called the ‘Lake Wobegon effect’, this is the tendency for most people to believe that they are above average in traits like intelligence, driving ability, job performance and in this case investing ability.

This is of course a fallacy: not everyone can be above average. Many investors overestimate their ability to keep calm during panics and crashes, to absorb short-term losses and hold onto investments that will benefit them in the long run. In other words, many investors believe themselves to be sharks, when in fact they are suckers.

To be a successful investor requires some introspection and honesty. What kind of temperament do you really have? If you are a true cold-blooded shark, then I congratulate you and would invite you to consider my colleague’s high volatility portfolio.

If, however you are less inclined to an investing experience red in tooth and claw there are other approaches. Portfolios can be diversified with other assets, a topic of discussion of another day, but even within the equity element of a portfolio strategies can be selected that are less volatile and inclined to conservatism.

For example, take the Troy Income & Growth (TIGT), where the managers are committed to an absolute return approach rather than overly concerning themselves with performance relative to a benchmark. The focus on capital preservation is reflected in the volatility of the trust’s NAV, which was 13.5% versus the FTSE All-Share Index of 16.8% over the past five years.

When markets fell in March 2020 this approach demonstrated its worth, the average trust in the UK Equity Income peer group fell peak to trough by c. 30%, the trust with the lowest loss in the peer group was Troy Income & Growth which only fell c. 19%.

Now, the UK Equity Income peer group would be considered by some to be a relatively conservative peer group to begin with. However, the philosophy of seeking growth without taking unnecessary risks can be applied to areas traditionally thought of as being a bit racier. Take for example Aberdeen Standard Asia Focus (AAS), a trust which invests in Asian smaller companies. This is clearly a strategy focussed on profitable opportunities in rapidly growing markets. However, the managers do not simply ignore risk, and emphasise the high quality of the companies they own which makes them more resilient to poor markets or economic environments.

This approach has led to materially lower volatility than the MSCI AC Asia Pacific ex Japan benchmark, in this case 13.8% versus 14.9% over the past five years. It turns out the promises of the East do not require reckless adventurism, and this highlights the more general point that it is possible for investors with less inclination to risk to participate in markets without becoming suckers.

Don’t be distracted by the short term – Thomas McMahon

Behavioural finance is cool. Like table magic it offers the possibility of outsmarting peers and competitors with hidden knowledge. My colleague’s argument about volatility is interesting, but I would argue investors would do better to focus on doing the basic things right rather than over-complicating investment. The goal of investment is ultimately to make money. I think focussing on volatility can distract from this in a couple of ways.

The first is that focussing on volatility brings attention back to the short term from the long term, where it should ideally be. Successful active investors tend to have a focus on the long term, as long-term returns tend to be driven by trends which can be more easily forecast. This is of course relative! It is not easy by any means, but chasing markets in the short term is like trying to herd a fly out of a letterbox. It is also expensive, considering trading costs.

Some of the best long-term returns have come from trusts with high volatility. To my mind focussing on the volatility is putting the cart before the horse. It is true that there will have been times over a five- or ten-year period when investors will have seen their holding in high volatility trusts like Scottish Mortgage or JPMorgan China Growth & Income (JCGI) fall by a considerable amount, but this should be irrelevant if the investor remains focussed on the long term.

The second reason I think volatility can be misleading is that a well-constructed portfolio should see a considerable diversification gain when considering volatility at the portfolio level. I think investors would do better to focus on picking the managers they think can outperform over the longer run and then ensuring they are not exposed to one strategy, style, geography or other factor.

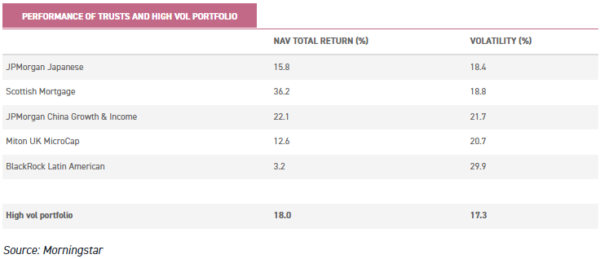

To illustrate my points, I have created a portfolio of five high volatility trusts. They are diversified by geography and by style, with varying sector exposures and very different stock picks. As can be seen in the table below, looking back over five years each has a highly volatile NAV in isolation, on average 21.9%. However, investing 20% in each of these five years ago would have created a portfolio which displayed volatility of only 17.3%. This is without any rebalancing, and using only equity trusts.

This suggests an investor who uses the volatility of individual funds as a guide for what to expect at the portfolio level would be misguided. Moreover, our portfolio would have generated 18% a year in NAV total return terms, a pretty decent result with the MSCI ACWI up only 13.2% p.a. over the period. Scottish Mortgage and JPMorgan China Growth & Income have been the best performers, while BlackRock Latin American (BRLA) and Miton UK MicroCap (MINI) have lagged in relative terms over the period. Both have had shorter periods of exceptional returns in this timeframe though. Taking this approach to diversification means accepting that some of your high vol / high return potential picks won’t come off in each period. There are potential environments in which both of these would do exceptionally well while SMT and JCGI fall back – and given the current situation in China and outlook for rates it is feasible one such scenario could be on the horizon.

Another factor to consider is that in the IT world, trusts which gear up are likely to have higher volatility. Boards seem generally quite hesitant to employ significant amounts of gearing in the equity space, which may be a lingering effect of the 2007/2008 financial crisis. JPMorgan Japanese (JFJ) is one trust to benefit from significant levels of gearing, averaging just shy of 10% over the past five years. We think gearing is a key advantage for investment trusts, and assuming markets rise over the long term – and boards resist the urge to gear at market highs and de-gear at market lows – should lead to higher volatility of NAV and higher returns for investors with a long-term time horizon.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.