May

2021

Shoot to Thrill: ISA targets for long term growth

DIY Investor

8 May 2021

This is not substantive investment research or a research recommendation, as it does not constitute substantive research or analysis. This material should be considered as general market commentary.

We all intend to invest for the long-term but can often be distracted by the news…

We all intend to invest for the long-term but can often be distracted by the news…

In times of crisis, the Romans would consult the Sibylline Prophecies. Contained therein was a prophecy that the 12 vultures seen by Romulus as he founded Rome (despite founding a start-up he still had time left for birdwatching, living before the modern-day culture of investors demanding updates) represented a signal that the primacy of Rome would last 12 saecula, a saeculum being a period taken as something between 85-100 years.

With Rome and the Western Roman Empire falling to the Visigoths in 410 AD the prophecy proved rather astoundingly accurate (this representing 1,163 years since the legendary founding, or c. 97 years per saeculum).

Sadly, the prophecies have been largely lost, so we cannot whether the next Great Pub Re-openingTM of April 2021 will prove to be permanent and sustained (though we hear that teams of publicans are even now trying to coax Indiana Jones out of retirement).

The end of the tax year is upon us, meaning ISA allocations need to be used or lost. Unfortunately, we can’t consult the Sibylline Prophecies to identify investment opportunities but must instead make do with the inadequate substitutes of data examination, qualitative reasoning and logical deduction.

And the occasional omen (I won £4 on a scratch card just after drinking a Yamazaki, and you want to tell me that isn’t a sign I should buy Japanese stocks?!).

Valuations, margins, productivity growth, inflation, demographics, the balance of income within an economy; all of these factors will impact over the long-term, even if their impact is less tangible in the short-term.

We have focused on where we think the best opportunities are for growth in equities over the coming ten years, yet there will surely also be further opportunities in other asset classes.

Nor do we think you should simply forget about your investments for the next ten years; markets and economies are capricious and outstanding entry and exit points will doubtless emerge over this period.

Clearly investors need to continue to consult trustintelligence.co.uk on a regular ongoing basis to stay abreast and identify ongoing opportunities. Nonetheless, it is good to have a long-term framework to provide a structure for more near-term considerations.

Is something else rising in the land of the rising sun? Buy Japan

As we have quoted the Oracle of Omaha above, let us start with the Japanese market, to which, notably, Berkshire Hathaway started to allocate in 2020.

In general, Buffett is considered a ‘value’ investor. Taken in the classical Benjamin Graham sense, we would suggest this is a misunderstanding of his strategy from the mid-70s onwards.

We believe Buffett looks for oligopolies with sustainable margins which they have room to continually, incrementally, and reliably improve with relatively minor needs to reinvest to sustain competitive advantage.

At first glance, these would not seem to be common in Japan. The Japanese market is exceptionally deep in companies, and often vastly fragmented. Yet over the past few decades there has been a certain concord across much of the economy and society, in alignment with much of Japanese history.

This ensured that Japanese companies retained employees and maintained wages throughout the slow nominal growth of the 90s and 00s. In return, they were somewhat compensated by superior productivity growth over this period from their workforce1, but the debt overhang and disinflationary headwind of a diminishing workforce weighed against aggregate growth.

Yet unemployment remained low and real wages relatively high. In essence, this was a long-cycle rebalancing in the favour of labour share of income at the expense of capital (mitigated by the fact that much of the Japanese population is well-off and many are participants in the capital performance of the country’s assets through ownership).

With the ascension of Shinzo Abe and the economic program of ‘Abenomics’, the momentum started to slowly shift back towards the owners of capital. Should this be sustained, it should ultimately be beneficial to shareholders.

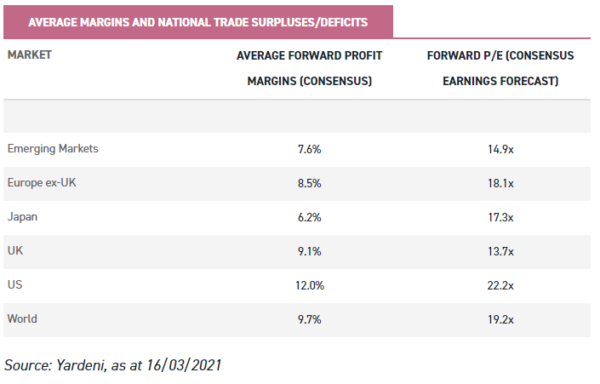

There seems, in our view, plenty of capacity for this to be the case (for capital to gain economic share at the expense of labour). Margins are low in Japan relative to the rest of the world, whilst the historic trade surplus has dissipated (trade balances in major countries should typically be mean reverting in major economies over the long-term, bar the US).

This latter consideration suggests that Japanese companies have the potential to take international market share as well as domestic.

Although investors may prefer wider margins (understandably), over the long-term margins are very mean-reverting and this mean reversion is an essential feature of capitalism, as Jeremy Grantham has pointed out.

Whilst there is no equilibrium around which all major economies should expect average margins to oscillate (Japanese and US markets likely do not have the same point of equilibrium, for instance), notably lower average margins in the Japanese corporate market suggests to us that there is greater room to pass on any rising input costs to consumers. It also suggests there is room for consolidation and greater efficiency of capital deployment and business operations.

It was in part the opportunity for greater capital efficiency, and easy upgrades to margins relative to global peers, that led the team behind AVI Japan Opportunity (AJOT) to launch their trust in 2019.

Noting the exceptional discount and financial strength of the Japanese market, and that their stock universe displays these characteristics even more strongly, the managers took positions in companies where engagement with company managements can, they believe, readily produce shareholder uplift.

This was further tied into the ‘Abenomics’ push, which explicitly targets improvements in corporate governance.

If stockholders do not wish to recognise the exceptional value in many of these companies, companies themselves are not so shy. Merger &

Acquisition activity has been on the rise in Japan in recent years, and an exceptionally deep stock universe leaves room for consolidation and for leading companies to take market share.

The managers of JPMorgan Japan Small Cap Growth & Income (JSGI) look to take exposure to companies that can benefit from precisely these trends, whilst incorporating exposure to areas deemed to be thematic and structural growth opportunities.

We have previously covered some of these considerations around the ‘new Japan’ here.

Amongst these themes in the ‘new Japan’ is the idea that the next wave of technological innovation and productivity development will come from increased automation.

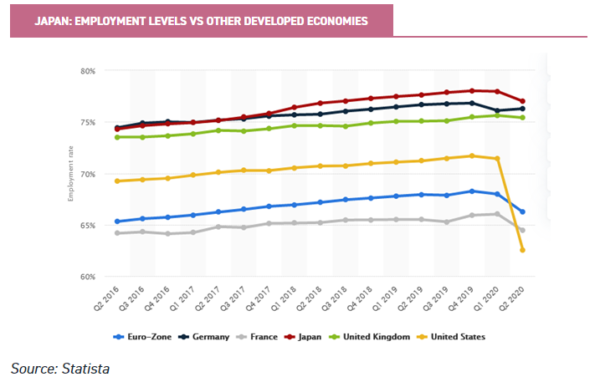

Amongst major economies, Japan seems better placed to offset the social pressures implied to employment conditions, with the lowest unemployment numbers and seemingly greater social cohesion.

Germany’s seemingly structural trade surplus is the result of an artificially depressed exchange rate which has seen German labour systematically underearn in real terms since c. 2003; the gradual rise of fringe political parties reflects this, in our opinion.

If it is likely untenable for German companies to en-masse integrate robotics at the expense of the workforce, imagine a broad move in this direction amongst Italian or French workforces….

In this context, low unemployment numbers could give Japanese companies latitude not to raise wages, in contrast to what we would by default expect.

Much of the leading technology is, in any event, created by Japanese companies such as Keyence, so there is no particular need for an erosion in the balance of trade as part of any broad move to integrate the necessary technology.

A rising tide will lift all boats, but higher quality companies will compound better returns operationally from integration or defeat of weaker peers. Strategies such as Coupland Cardiff Japan Income & Growth (CCJI) stand to benefit from these trends.

Metal Machine – are commodities set for a super cycle?

We have on several occasions highlighted our bullish outlook on commodities for the long-term, and the managers of Blackrock World Mining (BRWM) recently covered much of the backdrop in detail in an online webinar (available here).

We would suggest that an epochal change in supply discipline and capital management within the industry has potentially taken place and that since the nadir in 2015 these trends have persisted.

In the near-term, some caution may be warranted on industrial metals. Copper, ‘the only metal with a PHD in economics’ (a stupid expression, as copper has a far better record as a leading indicator than the economics profession in our opinion), looks very overbought on technical measures.

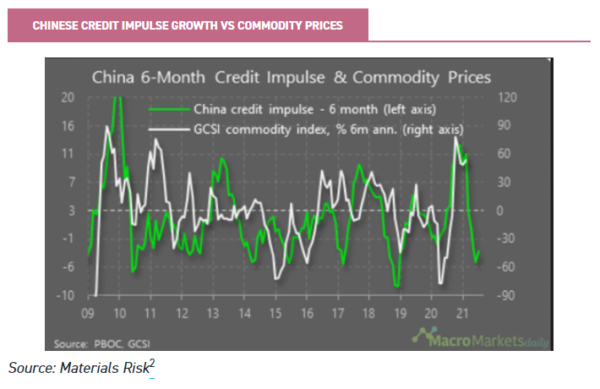

We can also see that the Chinese ‘credit impulse’ is fading drastically, and a key buyer should be considered likely to see lower aggregate demand for raw materials.

Past performance is not a guide to future returns.

However, it may be of comfort in this regard that the managers of BRWM note that current copper supply is seemingly being bought only to meet current demand (i.e. there is limited to no building of strategic reserves in the current market).

Given strategic reserves globally have been reduced (as the managers of BRWM highlighted recently) and mooted infrastructure projects have yet to take-off, in the long-term this gives more confidence that seismic recent gains are a reflection of market pressures and not governmental intervention.

As it takes multiple years to bring new supply on-line in the mining industry, a period of extended exploration and development discipline over the past 5-6 years offers further confidence that the supply-demand pressures pushing spot prices higher can be sustained.

Even if we were to see an extended consolidation period in copper and/or other industrial metals (perhaps understandable, if the market has got ahead of expectations of economic recovery), we are bullish on the potential for gold and precious metals.

These themselves have endured their own consolidation period in the last few months, but we believe the fundamental outlook remains positive (as discussed here).

Zero-carbon targets and severe supply discipline against a pipeline of reasonably assured demand growth seems to suggest there may be a significant opportunity in uranium miners. Recent gains have been strong, but we think they may just be getting started.

Hydrogen has become more topical within the investment community too, and, in contrast to previous expectations of a hydrogen takeover, there appears to be real demand from the industrial side at this time.

Feeding into our bullishness on the UK small cap sector, we note that some of the leading producers of hydrogen energy production technology are UK based, and have agreed partnership agreements with the likes of Shell and Siemens.

The market perception of this sub-sector looks somewhat ebullient at present, but perhaps this suggests there are possibilities for ‘new world’ energy in the ‘old world’ energy complex?

In any event, markets have dramatically readjusted to the likely reality that the run-off value in oil is worth something. Straddling the energy complex as well as materials, Blackrock Energy & Resources Income (BERI) should perhaps be on some radars.

Wherever I may roam – look beyond the index for GEM opportunities

China accounts for an increasing proportion of the MSCI Emerging Markets index. We think the greater opportunity for emerging market investors over the coming decade likely lies elsewhere.

Above we have noted and linked to some of the bullish potential backdrops for commodities. As we discussed back in December, rising commodity prices boost the terms of trades in many emerging market countries, but decidedly not in China (more below).

Brazil stands out as a potential winner if we do indeed see a commodity boom over the coming years.

We start with the fact that the Brazilian market is relatively cheap compared to emerging market peers; Brazil trades on a cyclically adjusted P/E (CAPE) of 15.5x, compared to a MSCI Emerging Asia-Pacific CAPE of 17.1x3.

As CAPE measures the inflation-adjusted average earnings over the previous 10 years against the current price, it is less skewed by performance over the previous 12 months, which we think is particularly relevant at this time given circumstances over 2020.

However, we should then factor in the fact that the last ten years have been incredibly challenging for the Brazilian corporate sector.

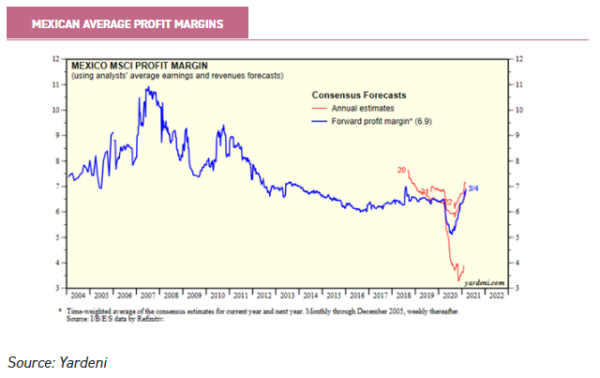

Brazil endured its worst-ever recession in the early 2010s, and unsurprisingly earnings cratered again in 2020, falling c. 28.8% (Source: Yardeni). However, if we see a reflationary environment globally then we will see a much more supportive environment for the Brazilian economy.

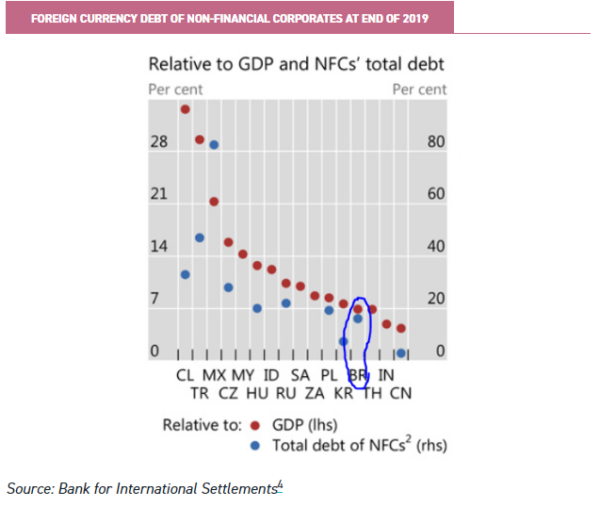

In any event, Brazilian corporates have, as is so often the case, proven more responsible coming out of the crises than going in and have reasonably constrained levels of foreign debt (however, it should be noted that stringent disclosure requirements on the Brazilian stock exchanges does raise the possibility that further foreign currency liabilities are, in effect, hidden through overseas listings of Brazilian companies).

When we then look at the Brazilian market CAPE of 15.5x and compare it to a trailing P/E of 32.3x, we estimate that trailing 12-month earnings are c. 48% of their inflation-adjusted ten-year average.

That is to say, they are currently less than half of their average over what is probably the worst decade in Brazilian economic history. A degree of rapid recovery is likely priced in, but a forward P/E of 9.4x against consensus-estimated 12-month earnings growth of c. 128.8% for the market as a whole does not seem demanding.

Strategist Vincent Deluard of StoneX has noted that if you valued the Brazilian market by inflation-adjusted earnings from 2000-2010, instead of 2010-2020, the market would trade on a CAPE of c. 8.1x, compared to c. 48x for the US. What if the 2020s are more like the 2000s than the 2010s? All of a sudden, a cheap Brazilian market looks markedly cheaper.

Against this we must set the recent annulment of Lula’s corruption charges, and rumours of fractiousness between Finance Minister Guedes and President Bolsonaro.

A bull thesis predicated on the concept that we are in the latter stages of Corporate Darwinism (any Brazilian company that has survived the most recent epoch must have resilience) might yet face challenges if, instead of further market consolidation and ability to expand margins, companies face a Brazilian state regressing further into dirigisme. Yet this seems very in the price.

Brazil makes up the majority of the Latin American index, and much of the remainder will typically consist of Mexico. These are, indeed, the two biggest market weightings in Blackrock Latin American (BRLA), who recently updated on their outlook. If a post-NAFTA recalibration is indeed in the works, Mexico could undoubtedly face challenges. Yet we again find a, not unreasonable, CAPE of 14.9x, against the backdrop of a decade where average profit margins have been low. Much seems, we would suggest, to be in the price.

Stepping away from Latin America, India retains significant structural drivers of growth that trusts such as Ashoka India Equity (AIE) remain exposed to. We covered the long-term thesis here, and believe this remains intact.

Gott Min Uns: UK small caps- capital efficiency could mean a big opportunity

Presently the UK is amongst the cheapest of all major markets, if not the cheapest (depending on which valuation methodology is employed).

After years of perceived political uncertainty and turmoil from a variety of sources, many international investors have seemingly been wary of over-allocating to the UK. This can perhaps be seen in the lower valuation attached to the UK market.

Yet we think there remains a very attractive investment opportunity in UK equities, and particularly amongst UK smaller companies (as we have discussed in more detail here).

Headline valuations are attractive but do not necessarily denote strong future returns (after all, the Russian market has been exceptionally cheap for an extremely long period of time).

However, with the agreement of a Brexit deal and greater certainty, there are already signs that international investors are returning to the UK market, and this should provide an additional tailwind if it persists.

More pertinent is the exceptional depth of the UK market, as highlighted by the managers of Miton UK Microcap (MINI)(and we will be covering the structural backdrop which MINI’s managers think will provide a tailwind to UK small caps further in our forthcoming note, click here to receive a notification when published).

Abundant opportunities exist in high-quality companies for active managers, and in the small-cap universe there are multiple companies whose growth prospects are likely endogenous.

Increasing moves to bring scale to asset management have made accessing these smaller, less liquid, opportunities harder for many asset managers to take positions in them.

When even marginal improvements to flows to such thinly owned areas of the market occur, outsized gains can be accrued.

This can be seen in the significant outperformance of trusts such as MINI and Aberforth UK Smaller Companies (ASL) in recent months following the announcements around COVID-19 vaccines in November 2020.

With Research Affiliates noting that the ‘value-to-growth’ discount based on fundamental value is in the 98th percentile (i.e. has only been wider on less than 2% of occasions), we think there is plenty of room for UK value to run.

Research Affiliates further note that the UK market is cheaper than all major peers on a price/five-year average cashflow basis, and in the 76th percentile of historic valuations on this basis5.

There seems to be a clear long-term opportunity here to us, and we note that several multi-asset investment trust managers have suggested they are seeing opportunities in the UK market (such as the managers of Seneca Global Income & Growth (SIGT) and BMO Managed Portfolio (BMPG/BMPI)).

TWEI (Tech Will Eat Itself). Buy small-cap tech, sell large

In the short term, ‘economic normalisation beneficiary’ stocks in the US, in particular, look extended.

With surveys suggesting that a significant proportion of stimulus cheques are likely to be spent on stock markets, expect this to extend; we would suggest that readers don’t try and second guess this or be too clever, just be aware of it.

With regards to the technology sector, we think the main issue at hand will be antitrust.

We have written before about antitrust and the evidence of regulatory capture in the US. Signs of pushback on the standard judicial interpretation (aligned with the Bork doctrine) would always have to be taken tentatively at best.

However, the bipartisan nature of much of the recent antitrust clamouring in the US houses of government suggests both parties may see votes in the matter. More pertinently is the nature of the language used, we think: comments from members of both parties that antitrust is not a matter simply of pricing power, but of economic power echo exactly the comments of Justice Brandeis6.

We think we could be looking at a seismic, enduring cyclical (long-cycle) turn in interpretation over the coming years (we have discussed this further below under the USA).

The implications for technology investing are potentially huge; for many of the biggest winning stocks, they are negative, but this need not necessarily be so for the sector.

However, eternal cash burn on the expectation of future market dominance will no longer be a viable position.

Previously, firms could expect equity financing ad nauseam until they reached such a position, secure that they would likely be safe from antitrust enforcement because they did not pass costs onto consumers (and instead leveraged their dominance over suppliers of goods, services, or revenues).

Instead, there will be a need for a more near-term need for cash realisation at all levels of the supply chain. This is a potentially self-feeding cycle. Managers with experience of the small and mid-cap technology universe such as Allianz Technology Trust(ATT), who place an emphasis on identifying

cash flow positive companies in any event, could well continue to identify new opportunities where there is less emphasis on ‘blue-sky’ possibilities or the necessity of building to scale.

A holding in technology also, frankly, hedges out portfolio relative risk (to a neutral market weighting) from the likely direction of travel that most of the other recommendations here imply.

Conclusion

The world is a big place, and there are no shortage of opportunities out there. Nothing is certain, but we think there are opportunities across the world for long-term investors willing to withstand short-term volatility.

Yet we also think there are narrative traps formed by the heuristic bias of the market. Conventional wisdom, such as ‘the market always goes up over time are easily disproved by looking at the market history in various markets across the world (yes, the Japanese market has finally recovered to its 1990 levels, but a 30-year period of negative returns would test the patience (and longevity) of most investors).

Focusing on where growth can be generated, and on the likely sustainability of expanding margins and market consolidation, can be coupled with historic valuations.

Over the longer term, the balance of national income share between labour and capital, and the direction of travel, will have a seismic impact on corporate earnings; regions/countries where there is room for capital to take income share stand in better stead on a fundamental basis, with greater sustainability of margins and room for margin expansion. Similarly, alterations to national trade balances will feed through to the corporate sector.

A global shift in emphasis to fiscal policy as a tool of support for economic growth may result in us leaving the disinflationary epoch nearly all of us have experienced for the totality of our careers, by-passing the credit creation mechanism of fractional reserve banking, and injecting the increase in money supply directly into the economy.

In other words, governments are likely to focus on raising fiscal expenditure and therefore deficits in order to boost demand instead of relying on corporates and households to borrow in order to spend.

This seems likely to be endemic across the world, but if governments wish to avoid crowding out the private sector it is likely that much of the resulting debt will effectively be monetised, and that we will see some form of yield curve control (arguably we already are seeing this, particularly in the Eurozone).

We have seen this previously in the US from 1942 to the mid-50’s, but the world is a different place and, more importantly, is now effectively on a USD standard.

What happens if we see regime change here? We have previously commented on the manner in which USD liquidity is key to global trade, and how even perceived reductions can lead to a dramatic repricing of insolvency risks; a change in trade-settlement terms could dramatically change how markets perceive and react to central bank policies the world over.

Starting valuations do still matter, especially at the index level; remember that stock returns are essentially the change in valuation, the change in fundamentals, and dividends.

And whilst the post-COVID-19 world may seem like a corporate Thunderdome (for every two that go in, only one may emerge), the capacity of economies to absorb such concentration of market power varies drastically. We would favour those with the capacity to allow ‘corporate Darwinism’ and shun those which cannot.

[1] https://www.ft.com/content/7ce47bd0-545f-11e8-b3ee-41e0209208ec

[2] http://materials-risk.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/image.png http://materials-risk.com/chinas-credit-impulse-running-on-fumes/

[3] https://www.starcapital.de/en/research/stock-market-valuation/

[4] https://www.bis.org/publ/qtrpdf/r_qt2006b.htm

[6] For more details, we recommend Tepper and Hearns The Myth of Capitalism, and, for a more partisan but still pertinent overview of the history of swings in antitrust cycles, Matt Stoller’s Goliath.

Click to visit:

Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future results. The value of investments can fall as well as rise and you may get back less than you invested when you decide to sell your investments. It is strongly recommended that Independent financial advice should be taken before entering into any financial transaction.

The information provided on this website is not intended for distribution to, or use by, any person or entity in any jurisdiction or country where such distribution or use would be contrary to law or regulation or which would subject Kepler Partners LLP to any registration requirement within such jurisdiction or country. In particular, this website is exclusively for non-US Persons. Persons who access this information are required to inform themselves and to comply with any such restrictions.

The information contained in this website is not intended to constitute, and should not be construed as, investment advice. No representation or warranty, express or implied, is given by any person as to the accuracy or completeness of the information and no responsibility or liability is accepted for the accuracy or sufficiency of any of the information, for any errors, omissions or misstatements, negligent or otherwise. Any views and opinions, whilst given in good faith, are subject to change without notice.

This is not an official confirmation of terms and is not a recommendation, offer or solicitation to buy or sell or take any action in relation to any investment mentioned herein. Any prices or quotations contained herein are indicative only.

Kepler Partners LLP (including its partners, employees and representatives) or a connected person may have positions in or options on the securities detailed in this report, and may buy, sell or offer to purchase or sell such securities from time to time, but will at all times be subject to restrictions imposed by the firm’s internal rules. A copy of the firm’s Conflict of Interest policy is available on request.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.