Jan

2024

Share the wealth, Xi…

DIY Investor

25 January 2024

The world’s most successful communist country could benefit from a decent welfare state…by Ryan Lightfoot-Aminoff

The Chinese economy has had a tumultuous couple of years. The impact of the Covid pandemic has cast a long shadow due to the enforcement of strict zero-Covid policies long after other major economies had fully reopened. Following a rare uprising of public dissent, these policies were quickly abandoned, leading to a peaking of speculation that China was soon to benefit from the revenge spending seen in Western economies, as the pent-up demand from lockdowns was let loose on the economy.

However, this failed to materialise in 2023 and the optimism soon faded away, despite the Chinese government’s piecemeal attempts to kickstart its flagging economy. We speculate that there is one major reform the government could roll out that would inspire an economic comeback, and one that many would assume is already in place … modernising to a comprehensive welfare system.

China woes

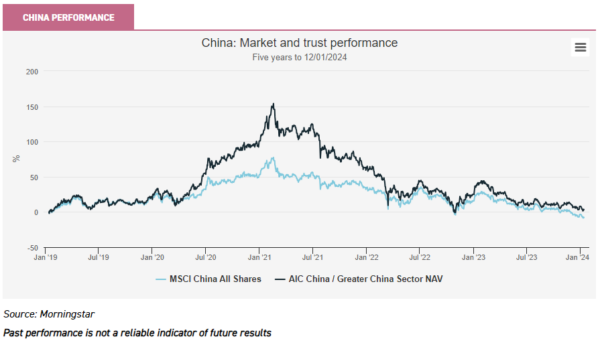

Before delving into solutions, it is worth analysing the anatomy of the fall. The zero-Covid policies were rapidly lifted at the end of 2022, just after a series of protests in a country that is famously robust on dissent. The market reacted quickly, with the MSCI China All Share Index climbing by c. 33% from the beginning of November to a peak in January 2023. Discounts on the four China investment trusts followed, moving from an average of 14.8% on 01/11/2022 to 4.4% on 01/02/2023. However, this rally soon petered out. Company fundamentals failed to keep up with the optimism and the Chinese market ended 2023 20% lower than at the start. At time of writing the index is at the lowest level in over five years, although the investment trusts have considerably outperformed this on average. The discounts, however, have widened to an average of 9.4%.

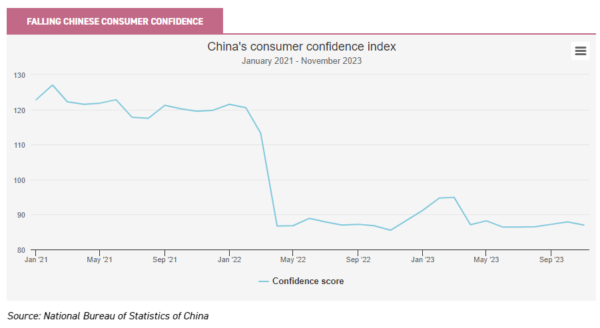

The primary reason for this aborted recovery has been the debt troubles in the real estate sector. The property sector is a major part of the Chinese economy, estimated to contribute between 25% and 30% of GDP. However, after years of relentless rises the speculative bubble burst on property prices, leading to a number of big developers going bust and creating ripple effects throughout the country. One consequence of this was a drop in consumer confidence. Property is seen as a key investment market in China and the rises of the past decades increased the wealth of many. But this reversal has led to caution, with citizens feeling less well off than they did a before the crisis, causing their propensity to spend to drop.

Additionally, unemployment, particularly amongst the youth, increased in 2023. The number of 16- to 24-year-olds out of work in urban areas hit a new record high in July of last year, topping out in excess of 20% before the government simply stopped publishing data. This has further impacted the outlook for the Chinese consumer and contributed to a slowdown in the economy. This soon led to a pullback in markets, leading to investors looking to the government for a response, much as it has done in the past. However, the government has made small and targeted changes, aiming to resolve specific issues as they emerge, such as reforms for housing developers.

However, we believe there is one way the government could provide the boost markets are looking for, whilst dealing with the root cause of the issues of last year, and that is to commit to wide-ranging reform of the welfare state.

All the fun of the welfare

Many readers might be surprised that a country whose only real political option is the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has a surprisingly disorderly welfare system. Formal social welfare reforms only began in the 1990s, replacing the previous system that was based on local community and work units. These reforms introduced housing support, established labour laws, including subsidies for the poorest, and established the foundations of a pension system. These have developed since with a number of reforms, though this has left a system that is incredibly complicated, with big regional variations and across different levels of employment.

The current system can be categorised under three pillars. Firstly, there is social assistance, which is a form of minimum income. This is designed to support the poorest in society and lift all citizens out of extreme poverty. It is, in effect, the ultimate safety net, though recipients are ‘encouraged’ to find employment to ensure this isn’t required. The amounts made available vary significantly depending on region, and the assistance is means-tested depending on the household. As is the case with much of Chinese data, figures can be hard to come by, though the most recently published official figures in 2016 set the rate between $535 and $835 per person per year. Current estimates put this at c. $1,300 today. The second pillar is the social security system, which includes pensions, health insurance and some unemployment benefit. Whilst these are comprehensive in scope, they come with caveats. Employees make contributions to these benefits alongside the government, with varying levels of support depending on job type and region. Each is effectively an insurance system that the government makes a contribution to the premium of alongside employees. The third pillar is welfare services, which are in place to support the elderly and disabled. These are also means-tested and vary depending on local government policies.

All three of these pillars have significant variances depending on a citizen’s location, with a particular divide between those in rural versus urban areas and no allowances for internal migration, meaning two citizens in the same job could have different access to benefits depending on where they were born. Furthermore, the system is beset by poor management and has faced accusations of corruption, especially in more rural areas.

Ultimately, the system has many holes, inaccuracies and exclusions. This has led to what critics label a negative social yield, meaning the cost of the system outweighs the benefits. One contributing factor to the system’s inefficiency is, in our opinion, the strong association to employment. The floor of the system commendably protects individuals from extreme challenges and has all but eliminated abject poverty in the country. However, the gap between the average salary – estimated at $6.9k a year in the private sector and $12.5k in the non-private – and abject poverty is significant, especially so with further losses of other protections such as health insurance to factor in.

We believe this has contributed to the nervousness in consumer spending, which is especially problematic at the moment. Unemployment would have a major impact on an individual in China, with little support to fall back on. Furthermore, individuals have historically used property as the primary source of savings in the past, and with this also now looking questionable, it is no surprise to see confidence falling and spending drying up.

As such, one way of rebuilding confidence in the economy could be through reform of the welfare system. If there were more financial support on offer, it might boost confidence amongst the workforce, and therefore increase their propensity to spend. If a worker is more assured of their future, should they suffer a temporary setback through forces outside their control, then there should be less nervousness when economic uncertainty does emerge.

Recent evidence supports this argument. Consumption jumped when the government initially lifted restrictions following the first wave of the pandemic in 2020. Spending, mostly amongst wealthy consumers, quickly recovered to pre-pandemic levels due to the confidence that came from government support. LVMH, for example, saw a 65% jump in Chinese revenues in the second quarter of 2020. Luxury car sales in Shanghai doubled in the same period. Analysts at the time pointed to government stimulus in the likes of infrastructure projects as the reason for this, as wealthy business owners were the ones to benefit from the stimulus. However, low- to middle-income residents were notably left behind, with this cohort reducing their spending by 6.2% in the same time period, as the stimulus had limited direct impacts on their lives. We believe this demonstrates the effectiveness of government stimulus when it gets to its target, as well as the fact that lower-income Chinese consumers are unresponsive to the type of stimulus measures implemented so far. We think that developing a more comprehensive welfare system would do this for the millions of low to middle earners in the country, which will likely boost their spending. The question is whether the government will, or even can?

Can China change?

It is fair to say the Chinese government has plenty to focus on at the moment. They are suffering from a stuttering economy, a trade war with the US, and arguably the West as a whole, a declining population and a collapsing property market. There are plenty of major issues for officials to be focussed on. Reform of a welfare system that is already the largest in the world is unlikely to be a top priority despite the likely short- and long-term benefits.

The CCP’s current focus is on boosting the entire economy through investments in advanced technology, infrastructure, both home and abroad, and military modernisation to name a few. Advances here are intended to allow the country to lead the world in even more industries and exert soft power around the globe, strengthening the economic and political position of the country as a whole. Meanwhile, the current welfare system has already achieved its main goal of lifting millions out of poverty. The percentage of Chinese citizens suffering from extreme poverty – defined as those earning less than c. $2 a day – has fallen from c. 88% in 1981 to almost zero now. That equates to almost a billion people who have been lifted above the level of abject poverty. Further still, the percentage of citizens with health insurance is over 90%, albeit with the caveat of employee input, a figure that rivals that of the US. China’s welfare system has already done a lot, and asking for reform to support consumer confidence may undermine the system’s primary goal of providing assistance to those most in need.

Furthermore, there is the question of affordability. China has considerable debt, currently over 250% of GDP, leaving it behind only Japan on the list of most indebted global economies. This has helped fuel economic growth over the past number of years, but now has the potential to be a severe anchor on the economy if the recent slowdown in growth persists, best demonstrated by a recent downgrade in debt outlook by Moody’s. This issue could become increasingly problematic when taking China’s demographics into consideration. The country’s population is falling and ageing, which will further hamper future economic growth, something we have discussed previously. This means there will be fewer and fewer people in work to support increasing numbers out of it, which will be a major challenge in its own right, let alone when adding in the complication, and potential cost, of welfare reform. As a result, China’s highly indebted economy and ageing population could make undertaking potentially highly costly welfare reform less attractive.

Conclusion

Depending on your interpretation of the CCP’s supposed communist ideals, China’s welfare system ranges from a highly successful programme of poverty eradication to a flawed system full of inefficiencies and plagued by corruption. Either way, the lack of comprehensive cover has arguably contributed to weak consumer confidence that has mired the economy’s post-reopening recovery. Whilst reform would likely have a notable impact on confidence, we think the scale and cost are likely too prohibitive for the government, which is far too preoccupied with the myriad challenges the economy is already facing.

Instead, we would argue the government is likely to focus on improving the broad economy, meaning changes in consumer sentiment are more likely to be affected by the macro-cycle rather than internal reform. With major economies looking to avoid severe recessions in 2024, potentially avoiding them altogether, China could be well placed, considering its exposure to global manufacturing. This could provide an alternative, delayed but much welcomed boost to consumers. As such, we think a recovery in Chinese consumer confidence this year is far more likely to come from demand-led global economic growth, rather than through socialist policy reform.

There are a couple of interesting investment trusts offering a way to play such a recovery, both offering access at a discount to NAV, adding to the potential returns should a recovery come through. The first we would highlight is JPMorgan China Growth & Income (JCGI), managed by Rebecca Jiang and Li Tan, and supported by investment advisers Howard Wang and Simmy Qi. The team focus on identifying high-quality growth companies and backing them with conviction. The portfolio has a bias towards exposure to technology companies and those enabling the energy transition, which are fully aligned with the CCP’s strategic goals. The trust currently trades on a c. 9.9% discount, which could make a compelling entry point for long-term investors.

Investors could also consider Fidelity China Special Situations (FCSS), managed by Dale Nicholls. He has a small- and mid-cap bias, using the significant on-the-ground analyst team at Fidelity to discover under-researched opportunities often overlooked by other investors. Dale believes that valuations of Chinese equities are particular cheap at present and has increased net market exposure to over 128% in order to take advantage of this. The trust is also on a sizeable 10% discount, compared to the five-year average of c. 7%. The board of FCSS has also proposed a combination with abrdn China Investment Company (ACIC). If this is approved by shareholders, it will provide a larger asset base on which to offer better economies of scale, improved liquidity in the shares and lower costs. We believe this makes FCSS particularly attractive at the moment.

Disclaimer

This is not substantive investment research or a research recommendation, as it does not constitute substantive research or analysis. This material should be considered as general market commentary.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.