Apr

2024

Seoul searching

DIY Investor

3 April 2024

South Korea is looking to tackle its ‘discount’ versus other Asian countries by introducing governance reforms just like Japan’s…by Josef Licsauer

One of the catalysts behind Japan’s very recent 34-year stock-market high has been the demonstrable success of its governance reforms. Its ‘playbook’ is now being rigorously analysed by other countries in similar positions, with South Korea already taking inspiration from Japan’s decade-long governance push, announcing an almost mirrored programme in February 2024. We think this could lead to South Korean equities outperforming in the years ahead, seeing a similar impact as Japan has.

South Korea is well-known for many things and, in our view, 2012 pop sensation Park Jae-sang (creator of Gangnam Style) sits close to the top. Pop culture aside, South Korea is also well-known for having a cheap stock market, hence the concept of ‘the Korea discount’. Many companies sit at a price-to-book ratio below 1.0 and are known to have historically placed little emphasis on shareholder return policies, including dividends and buy-backs, and to have questionable corporate governance. South Korea wants to enhance the standards of its companies, bolstering shareholder returns and improving the overall growth outlook, and there are various strategies under consideration to aid in this quest. The one that currently shines brightest is the freshly announced, but eagerly anticipated, corporate Value-up programme. We think that while Japan has rightly garnered investor attention of late, the changes and events happening in South Korea could position it as a very attractive place to invest. In this note, we delve into the Value-up programme, deciphering what it means in practice and explore the potential opportunities in the investment trust space that may have gone unnoticed.

Why is the Korea discount a problem?

Before we dissect the Value-up programme let’s paint some colour around why it was needed in the first place. Simply put, the Korea discount dampens economic growth. It makes it harder for companies to raise affordable capital close to home and a lot of foreign investors are discouraged from holding Korean equities for the longer term, preferring to flip in and out of stocks for quick gains. Ironically, one of the drivers behind Korea’s decades-long transformation from economic minnow to industrial giant, is one of the reasons behind the country’s chronic undervaluation of stock prices.

Much like Japan has family-run conglomerates known as zaibatsu, South Korea has family-run conglomerates known as chaebols, including companies like Samsung and LG Electronics. They exert control over hundreds of listed companies, thanks to a complicated web of cross-shareholding and their founding families often control the boards and management of those listed firms. They are often accused of ignoring the interests of other shareholders, keeping share prices artificially low to avoid Korean inheritance tax, which is among the highest in the world. However, while chaebols play a crucial role there are other factors significantly contributing to the Korea discount, including traditionally low dividend payouts, inefficient asset utilisation among Korean companies and continual geopolitical tensions.

How discounted are we talking?

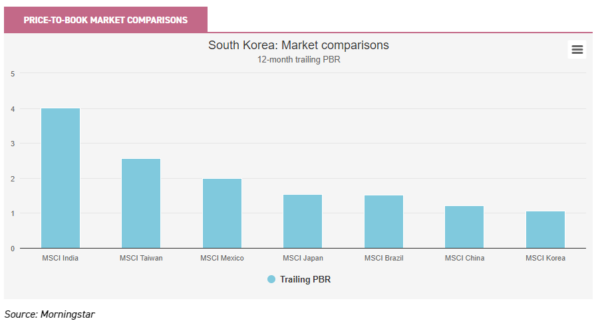

To help decipher this question, we’ve included a graph below that shows the price to book (P/B) of a range of markets. The P/B rating measures the market’s valuation of a company relative to the book value of its equity, and provides an indication of how cheap or expensive things are. Currently, South Korea has a P/B of 1.06, although it’s often traded below this, indicating it’s very cheap versus peers. In fact, looking at all 24 emerging markets, South Korea has the second lowest 12-month trailing P/B, with only Colombia boasting one lower. Unfortunately, including all 24, plus Japan, made the table below very messy, so our readers will have to take our word for it. It is notable though how cheap Korea looks to the major emerging markets and even to Japan. This comparison is even more stark when compared to a larger developed market, like the USA, which has a P/B of 4.7.

After taking an even deeper look at the data, we noted roughly two-thirds of companies listed on the Korean stock exchange, the KOSPI, trade at a P/B less than 1.0, and the average P/B of Korean banking groups is around 0.4, meaning their market value is much less than the value of assets on the balance sheet. Clearly, things look cheap, and for those shouting at their screens, what about Samsung! Well, even the bigger, more globally known names like tech titan Samsung Electronics aren’t doing much better. It currently trades at a P/B of 1.2, compared to TSMC, one of its closest rivals, which trades around 5.2.

Let’s Value-up

The corporate Value-up programme aims to home in on companies with a low P/B (just as Japanese reforms do) and to hold management more accountable for improving governance. It was announced on 26 February and in anticipation of its introduction, global investors have been pouring money into South Korea’s stock market in the hope that a government push on this scale will boost depressed valuations. The programme is split into three main pillars: a nonbinding guideline to incentivise better shareholder return policies, a new index to promote companies’ efforts to enhance their valuation and a bolstered government support system.

However, the KOSPI Index fell the morning of the announcement, with losses led by automakers and banks, sectors that had rallied hard ahead of the government’s reform proposal. In our view, there seems to be evidence supporting the adage: buy the rumour, sell the news. The programme fell short of market expectations for a few key reasons. The first came down to the fact the programme will run on a voluntary basis, essentially meaning there will be no legal obligation for companies to take part in the initiative. This was met with disappointment, but the Financial Services Commission argued it was more realistic and desirable to provide incentives to encourage participation than to coerce companies with regulations. Mandatory disclosures may lead to tokenism, making companies’ filings meaningless and perfunctory.

Moreover, there were no explicit or definitive measures looking at tax: “The government explores a range of tax incentives and benefits. Companies chosen for their high corporate value or outstanding improvements in value may receive awards and preferential treatment in tax policies”. Given high inheritance taxes, many expected clearer or more aggressive comments on this, particularly given our earlier point on chaebols keeping share prices artificially low to avoid it.

However, it’s important to remember that Japan’s governance successes were a result of efforts spanning over a decade. We think this is a promising start from South Korea and a step in the right direction, and ultimately leads to some interesting opportunities that may be flying under the radar, something a number of fund managers we’ve spoken to recently are seeing.

The managers of JPMorgan Global Emerging Markets Income (JEMI) have increased exposure to South Korea, having effectively been structurally underweight for many years. They have seen tangible changes in governance attitudes more recently, something that’s being reflected in dividend policies including shareholder returns, dividend payout ratios and buybacks. They found some compelling opportunities at low valuations that have already demonstrated improvements deriving from the governance changes, including car company Kia and Korean bank, KB Financial Group. Kia, for example, announced a 60% increase in the annual dividend, tracking in line with strong earnings growth over 2023.

Templeton Emerging Markets (TEM) is another option for gaining exposure to South Korea. The managers, Chetan Sehgal and Andrew Ness, are currently overweight South Korea, versus the MSCI Emerging Markets Index, but have trimmed exposure given its recent market rally. They like the long-term prospects in certain South Korean companies, like Samsung Electronics, Naver Corporation and LG Chemical. They also highlight the long-term potential of Samsung Life Insurance, an investment in the top ten currently, which rose on the back of South Korea’s corporate Value-up programme.

Mobius Investment Trust (MMIT) offers something very different in the emerging markets sector, as it predominantly invests in small and mid-cap companies listed across the emerging and frontier markets universes. Like Japan, it may take time for the governance standards to trickle down the market cap scale, however, the managers are optimistic on the long-term prospects for South Korea. They also believe it acts as an indirect route into China, given it offers better governance and transparency, investing around 15% in the region, through companies like Leeno Industrial, Classys and Park Systems, all of which have showcased strong share-price performances over the last 12 months.

Conclusion

Overall, we think South Korea is showing early signs of real positive change. While there are weak links in its chain, success doesn’t happen overnight. It will take time to perfect the Value-up programme and for wider incentives on tax, or penalties for the uncooperative, to become clearer and more impactful. In our view, those long-term patient investors looking for an alternative to China, or just a differentiated way to play emerging markets / diversify their global portfolios should be aware of South Korea. The trusts we’ve noted above, while varying in exposures, all sit on discounts wider than their five-year averages, illustrated in the table below, so could be an attractive entry point to gain exposure.

Trust discounts over five years

| CURRENT DISCOUNT | FIVE-YEAR AVERAGE | |

| Templeton Emerging Markets (TEM) | 14.7 | 11.6 |

| JPMorgan Global Emerging Markets Income (JEMI) | 11.9 | 8.4 |

| Mobius Investment Trust (MMIT) | 7.2 | 4.0 |

| Morningstar Investment Trust Global Emerging Markets | 11.0 | 9.8 |

Source: Morningstar

Disclaimer

This is not substantive investment research or a research recommendation, as it does not constitute substantive research or analysis. This material should be considered as general market commentary.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.