Nov

2021

Private Equity: Even better than the real thing

DIY Investor

17 November 2021

This is not substantive investment research or a research recommendation, as it does not constitute substantive research or analysis. This material should be considered as general market commentary.

We explain private equity and examine why tweaks to listed private equity trusts give the sector an advantage over the direct route…

We explain private equity and examine why tweaks to listed private equity trusts give the sector an advantage over the direct route…

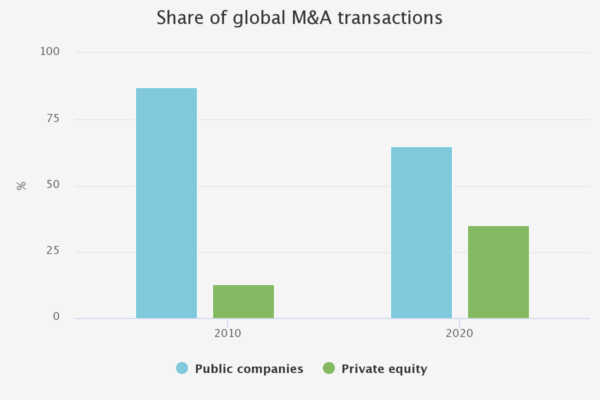

Private equity investing has been around for many decades. However private equity is making the headlines like never before. The recent bidding war for Wm Morrisons is a case in point although, over the last decade or so, private equity has been steadily increasing as a share of global M&A transactions as the graph below shows.

Listed private equity (LPE) trusts, which offer an exposure to private equity managers and their investment techniques, have similarly been a feature in the investment trust space for many years now, some dating from the 1980s. Despite their long heritage and strong performance (see below), LPE trusts have traded on wide discounts to NAV for more than a decade.

One of the chief reasons might be that listed private equity is not well understood by professional and retail investors alike. In this article, we attempt to go back to square one. We try to provide a clear picture of what private equity managers aim to do, how they go about it, and what the risks and opportunities are, before examining what investment trusts bring to the private equity party.

What is PE?

Private equity is a specialist area, in which capital is invested in unlisted private companies, or listed companies are taken over in order to take them private. The key differentiating factor in private equity (as we define it) is that the fund manager takes ownership control of companies they invest in, and plays a major role in setting the strategy, appointing and incentivising management, and decides when to sell the business to crystalise investment returns. These transactions are often referred to as ‘buy-outs’.

Private equity is often confused with venture capital (VC) investing, which typically differs in that the companies are less mature, and investments are made as a minority rather than as a controlling interest. As we highlight in this article, VC is considered higher risk than private equity by many institutions, but at times the higher risk may deliver higher returns.

The number of private companies vastly outnumbers those which are listed globally, and so the opportunities for private equity managers are correspondingly huge. In contrast to publicly listed companies, there are much less onerous reporting/transparency requirements for private companies, therefore less information may be readily available. Both of these factors mean that a private equity manager needs to be adept at sourcing potential investments themselves, not to mention having specialist skills in being able to evaluate them as potential investments.

Once they have been acquired, the private equity manager will aim to improve the management of assets, restructure the company, or merge it with other portfolio companies. Finally, after the necessary time to effect change and see the financial benefits of these changes, the private equity manager will seek to realise their investment and benefit from an improvement in the valuation of the business through an IPO, a trade deal or through selling on to another PE fund.

Investing through private equity funds & co-investments

Given private equity investing is so different to public equity investing, it will be no surprise that private equity funds are also structured very differently to funds investing in listed companies. Fundamentally, the principles are the same; managers will attempt to achieve a diversified portfolio of investments within each fund (within the confines of their area of expertise). However, given the illiquidity of these investments, this is where the similarities end.

Firstly, when raising capital from investors, private equity managers ask only for commitments of a nominal (maximum) amount. They then only ask for it (a capital call) when they have found a suitable investment and agreed terms. When they are made, capital calls are legally binding, and so investors are legally obliged to send funds when asked, giving managers (and sellers of companies) the confidence to agree binding terms with private equity managers.

Investors typically commit to a fundraising for a specific, fixed life fund of ten years. It will have a defined ‘investment period’ of c. five years, after which the manager is essentially not allowed to invest capital in new businesses.

Typically, private equity managers reckon on a three to five year holding period for investments, but every investment is different. The manager’s performance fee is typically only earnt once an investor has received their original capital back in cash, and a return of 8% per annum has been achieved, meaning strong alignment of interest between both parties.

With the clock ticking on ‘carry’ (or performance fee) once any capital has been drawn down (i.e. a capital call has been made), they are incentivised to maximise investment returns over as short a period as possible. Finally, it is rare that 100% of committed capital is called by managers and, once they have hit an investment level of c. 80-85%, they are allowed to begin fundraising for new funds.

In some cases, other than using investors’ commitments to fund an investment, private equity managers may offer ‘co-investment’ opportunities to investors in their fund, or other financial professionals. A co-investment is a stake in a company a manager is targeting for their fund, but which the investor holds directly outside of the PE fund structure.

This may be because the investment required is larger than might have been originally envisaged for the size of the fund, or it may be a result of a need for diversification within the fund. Either way, the lead private equity manager will retain control of the investment, but these co-investments are usually offered free of any fees.

Private equity performance

Because of the staggered nature of cashflows (in and out of the fund, as we describe above), comparisons of private equity funds’ returns with traditional equity fund returns are difficult to make. That said, the British Private Equity & Venture Capital Association (BVCA) publishes average returns of the UK private equity sector, which for the period to the end of 2019 had delivered strong absolute returns to investors on an IRR basis of 20.1% per annum over five years, and 14.2% per annum over ten years.

By comparison, The FTSE All-Share returned 7.5% and 8.1% to investors over the same respective time periods. It is fair to say that the past few years have seen a reasonable degree of financial stability, enabling private equity managers to deliver strong returns to investors.

At the same time, these statistics likely flatter the returns investors actually receive, given a private equity investor needs to keep their commitments to a fund in a readily accessible form (i.e. cash) until it is called. Private equity return statistics quite rightly only measure the returns on capital that are called and invested by the PE manager (this is the basis for the calculation of IRR). This is not directly comparable to returns in public markets, where an investor can fully invest their available capital from day one.

As such, it is rare that investors ever experience the same net returns as those implied by private equity managers’ investment performance. As we will come to later, listed private equity trusts provide a degree of mitigation on this ‘cash drag’ effect, by overcommitments and in some cases through the use of gearing.

Whilst the performance of private equity is impressive, it is worth being aware that private equity investing is not without risks. Private equity managers typically use more leverage in capital structures than listed companies. Fundamentally, the sector therefore benefits from favourable financing conditions – most especially low interest rates – which have led to plenty of availability of debt, as well as a return to ‘covenant-lite’ loans.

This should mean private equity backed businesses are potentially more resilient than the past, but it is an unavoidable fact that leverage is higher than with equivalent listed companies. All things being equal, if financial conditions become harder for an extended period, then private equity backed companies will find it harder to deliver the returns the managers hope to achieve.

In the same way, private equity investments’ illiquidity could mean that with elongated holding periods, annualised returns could reduce. And there is no guarantee that exits will be achieved at all. This is the reason why many private equity investors (LPE trusts included) found themselves overstretched in the global financial crisis of 2008/09.

With managers calling capital (to support existing businesses, or take advantage of low prices for new investments) at the same time as realisations slowed to a trickle, several LPE trusts found themselves having to perform rights issues at a steep discount to the prevailing NAV. Some – such as SVG Capital and Candover Investments – never recovered having been amongst the best performing managers previously. More conservatively managed trusts survived, but the LPE sector was hampered by very wide discounts for a number of years hence, and perhaps investors’ memories of this period are behind today’s discounts? That said, we believe the lessons of the past have been heeded, and that a repeat of 2008 for the LPE sector is unlikely.

How do private equity funds differ from ‘normal’ equity funds?

On the surface, private equity ticks a lot of boxes that investors nowadays look for in equity funds:

- High conviction

- Significant opportunities to add alpha

- Active management rewarded through enhanced performance

- Long term investment philosophy

- Strong historic returns.

Yet this is where the similarities with in-demand listed equity funds and trusts end.

In contrast to public equity managers, there are no relative benchmarks or volatility considerations which input into portfolio construction decisions. Instead, managers target absolute returns, with their efforts highly incentivised through performance fees (known as ‘carry’), which typically entitle them to 20% of portfolio gains over and above an 8% per annum hurdle.

In contrast to public equity managers, performance fees are only paid on crystalised gains – i.e. valuation increases will not lead to any performance fees being paid (although they will likely be accrued in NAV calculations).

Private equity managers typically specialise in a geography, sector or size of business, which enables them to capitalise on lessons learnt from past investments, but also build up a wide network of industry contacts or consultants to help them effect change.

This means that over time, and whilst every investment is different, private equity managers can justifiably claim that theirs is a repeatable process. Each investment is selected based on intelligence gained after many months of due diligence (aka research), and managers will usually have a very specific plan to grow earnings rapidly over the life of their investment, before achieving a full exit from their investment after this period.

Over the life of each investment, private equity managers expect to roll their sleeves up and work with the management of each investee company to execute the strategy. If a business hits an obstacle, then the private equity manager has a wealth of experience to help – financially (negotiating with banks), legally, or operationally.

There are plenty of anecdotal tales of the experience during early 2020 when the pandemic hit, where private equity backed managers of businesses were able to lean on a huge network of seasoned professionals in order to help them navigate this unchartered territory. For example, in the early stages of the pandemic, we understand that HgCapital organised a weekly conference call for the CEOs of their portfolio companies to compare notes and share ideas of best practice in how to navigate the challenges each of them was facing.

In contrast to listed companies, the managers of private equity backed businesses have a single person to report performance to, and can afford to take a long term view when making decisions. Again, in contrast to public companies, where quarterly earnings announcements are in many cases a main focus, private equity backed management can make investments based with an eye on one long term objective – that of selling the business for as much as possible in three to five years’ time. All of these factors mean that private equity backed companies are better equipped to deal with change, and outperform listed companies from an operational perspective.

Advantages of LPE

Private equity as an asset class has plenty of attractions, and in our view the way that the LPE sector offers exposure adds significantly to its attractiveness.

Size and access

Private equity managers typically only accept investments from institutions with a minimum commitment in the millions of dollars or pounds. Such is the demand for the best performing managers, some private equity managers have the luxury of being selective in who they accept investments from. In this way, long running fund of fund managers such as those who run listed private equity trusts have an advantage over those without such long running relationships, or who rely on less permanent pools of capital.

Within the private equity fund universe, the dispersion of performance between the best and worst managers is relatively wide (as one might expect from a high alpha strategy), meaning that fund of fund managers can potentially add significant alpha through picking the best managers. Within the LPE universe, the various funds of funds have very different approaches – either through concentration or through the characteristics of their preferred manager.

Many target the best performing established mid-market managers (i.e. the middle section of the market by deal-size), but BMO Private Equity Trust (BPET) differs from peers in that it targets less well established, smaller private equity managers who the manager believes will be better incentivised to hit or exceed their performance hurdle. In the same way, they target underlying investments that are smaller than the typical ‘mid-market’ deal size. On the other hand, Oakley Capital Investments (OCI) and HgCapital Trust (HGT) both specialise in sectors which they believe benefit from secular growth. For Oakley, this represents digitally-focussed businesses across Europe in three core sectors: technology, consumer and education, and for HgCapital in the software and services sectors. Both have been amongst the top performers in the peer group over the last five years.

Certainty of capital / co-investment opportunities

With their closed-ended structure, private equity trusts are well placed to participate in co-investment opportunities, and fund of fund managers who are set up to evaluate such opportunities can potentially significantly add to returns for shareholders by participating in them, such as ICG Enterprise Trust (ICGT) and BMO Private Equity Trust which have both had a strong NAV performance enhanced by co-investments. NB Private Equity Partners (NBPE) is distinct from the rest of the LPE universe, in that it invests solely in co-investments through third party managers which gives it the benefits of diversification, a single layer of fees and more control of its cash management (which allows it to run a geared portfolio).

LPE trusts gives them something of an advantage when it comes to accessing co-investments. The certainty of their capital means that as a counterparty, they are highly credible to private equity managers looking for co-investment partners. As such, co-investments usually represent a material proportion of fund of fund LPE portfolios.

The same permanence of their capital has led to some private equity managers such as Apax Partners, HgCapital and Oakley Capital having listed funds as a key strategic partner, which acts as a cornerstone investor. Some – such as HgCapital Trust – have advantageous terms which allow the trust to opt out of capital calls should the trust not have available capital which, however unlikely this might happen, does nullify the ‘black swan’ event risk.

Cash management

Closed-end funds are fixed pools of capital, which means they may suffer cash drag on uninvested capital, or if their managers cannot invest capital as fast as it is returned. LPE trusts have a variety of means to ensure they are as fully invested as possible to minimise cash drag, including over-committing to managers on the assumption that they will not all call for capital at the same time (or for the full amount committed).

In order to balance the risk that capital will need to be invested faster than it is returned, many trusts have an overdraft facility on hand to try to ensure they do not find themselves overstretched. This clearly carries risks, but LPE managers are experienced at forecasting and managing cashflows, and their ability to manage cash well will show up in the periodic reports they make.

The extent of cash and/or gearing drawn down is therefore an important metric to follow, and in our view the ideal is likely to be along the lines of Goldilocks’s porridge. Neither too much nor too little is probably about right, and will enable managers to navigate sudden changes to conditions without too much alarm from the market (which would be reflected in the discount widening out).

Some trusts – such as NBPE – specifically aim to run on a geared basis. Their ability to evaluate opportunities and deploy capital in real-time through co-investments allows this, and means the managers are able to be far more in control of their balance sheet than might otherwise be the case for a fund of funds.

Ready-made portfolios, conservatively valued

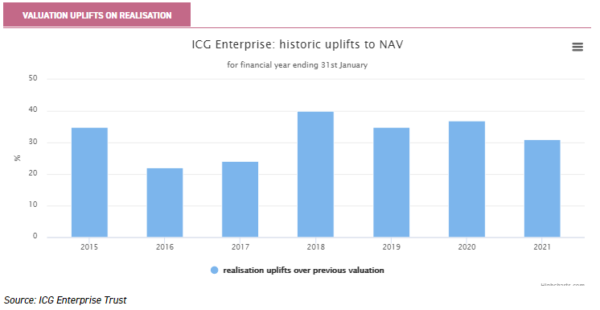

One of the biggest advantages for LPE investors, clearly underrated given their persistent discounts, is that trusts provide access to ready-made portfolios of private equity assets. These portfolios all take several years to build up through the commitment and capital drawdown cycle. Alongside this, private equity managers typically build in a degree of conservatism (or an illiquidity discount) when valuing their portfolio companies such that, when investments are realised, they typically fetch a premium of between 20-40% over the previously held valuation. In some cases, it can be higher or lower.

The graph below shows the valuation uplifts experienced by ICG Enterprise Trust over past financial years, which in our view illustrates the fact that valuations have been conservative. At the same time, it is worth noting that not all investments are ‘ready for sale’, which is why investors and managers like to look at the ‘vintage’ of a fund or portfolio which represents the first call on investors’ capital (or the first investment made within a fund). As we refer to earlier, with fixed lives and investment periods, this gives investors a rough guide on how soon realisations will start to be made. A typical rule of thumb is that realisations could start to be made after three to four years.

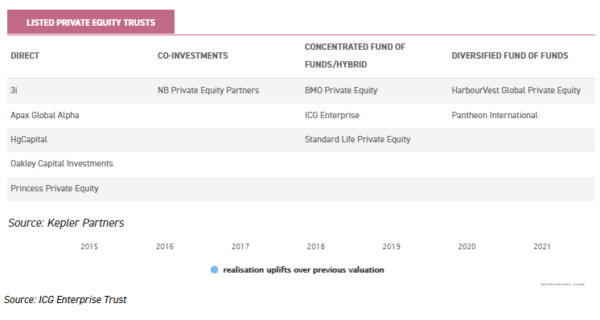

The LPE sector offers a wide range of different approaches and slants, which means that investors wishing to make a meaningful allocation can easily diversify their exposure to managers, sectors and approaches. In the table below we split the universe by the way each trust makes its investments. Direct LPE trusts have a single management group making investments, and tend to have very concentrated portfolios which in turn exposes investors to higher specific risk and potentially higher rewards.

On the other end of the spectrum are the highly diversified fund of funds which have underlying exposure to many thousands of private companies. Between these two poles, LPE trusts have more concentrated portfolios, but relatively little specific risk to individual companies. Investors can choose between these depending on risk appetites, sector preferences and premiums/discounts to NAVs.

Conclusion

Private equity managers create value in a repeatable process over cycles. The key reasons behind this – in our view – include long term thinking, the potential to invest in a much wider range of companies than those that are listed, an ability to influence change and improve companies’ operating performance, and a strong alignment of interests between investor and manager. With private equity as the engine, the LPE sector offers additional return drivers, which in our view mean the listed route is in some cases preferable to the route taken by large institutions. The discounts to NAV of today suggest that many people don’t share our view. But as trusts continue to deliver strong performance, we ask – for how long can investors ignore the space?

Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future results. The value of investments can fall as well as rise and you may get back less than you invested when you decide to sell your investments. It is strongly recommended that Independent financial advice should be taken before entering into any financial transaction.

The information provided on this website is not intended for distribution to, or use by, any person or entity in any jurisdiction or country where such distribution or use would be contrary to law or regulation or which would subject Kepler Partners LLP to any registration requirement within such jurisdiction or country. In particular, this website is exclusively for non-US Persons. Persons who access this information are required to inform themselves and to comply with any such restrictions.

The information contained in this website is not intended to constitute, and should not be construed as, investment advice. No representation or warranty, express or implied, is given by any person as to the accuracy or completeness of the information and no responsibility or liability is accepted for the accuracy or sufficiency of any of the information, for any errors, omissions or misstatements, negligent or otherwise. Any views and opinions, whilst given in good faith, are subject to change without notice.

This is not an official confirmation of terms and is not a recommendation, offer or solicitation to buy or sell or take any action in relation to any investment mentioned herein. Any prices or quotations contained herein are indicative only.

Kepler Partners LLP (including its partners, employees and representatives) or a connected person may have positions in or options on the securities detailed in this report, and may buy, sell or offer to purchase or sell such securities from time to time, but will at all times be subject to restrictions imposed by the firm’s internal rules. A copy of the firm’s Conflict of Interest policy is available on request.

PLEASE SEE ALSO OUR TERMS AND CONDITIONS

Kepler Partners LLP is authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority (FRN 480590), registered in England and Wales at 9/10 Savile Row, London W1S 3PF with registered number OC334771.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.