Aug

2021

Inflation – a real threat or hot air?

DIY Investor

7 August 2021

Two of our analysts ask whether recent high inflation numbers indicate something long-lasting and troubling is happening…

Two of our analysts ask whether recent high inflation numbers indicate something long-lasting and troubling is happening…

Inflation is here to stay – Callum Stokeld

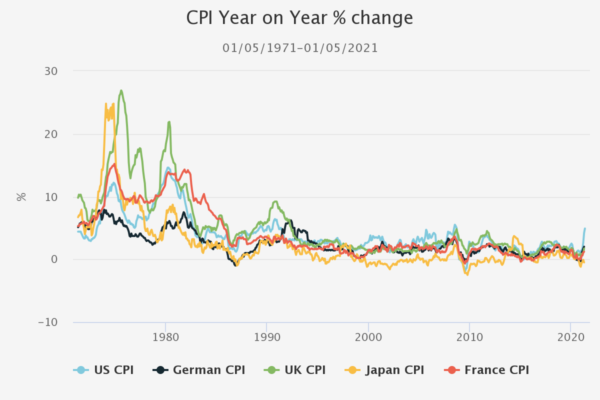

Are we in a different epoch with regards inflation? Over recent decades we have gradually seen inflationary impulses falling. With May 2021 seeing the highest inflation print since September 2008, I think investors are right to be concerned this might be sustained.

Source: St Louis Federal Reserve

Ultimately everyone dies, all our personal endeavours founder on the banks of time, our civilisation’s achievements rendered unto nothingness against the decay of history, with the sun itself burning out in around seven billion years1. You probably invest with a shorter time frame though, and the essentially transitory nature of existence is not as pertinent to your portfolio as whether inflationary pressures will persist or fade in the coming years.

Milton Friedman famously asserted that “Inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon in the sense that it is and can be produced only by a more rapid increase in the quantity of money than in output”. His famous equation stated that mv=pq, where:

M = the total nominal money supply in circulation in the economy

V = the velocity of money (the frequency with which a unit is exchanged)

P = the price index

Q = the quantity of goods and services.

Many have looked on in puzzlement in recent years as central banks the world over massively increased money supply and cut interest rates to the bone, only to see limited inflationary follow through. The velocity of money instead collapsed, with highly levered households and corporates unwilling in aggregate to be recipients of the additional lending enabled by the expansion in money supply.

Will this time now be different? The implications for investment strategies could be huge if so; we debate below whether investors should be readying themselves for a new investment epoch or whether the deflationary golem remains in control.

The human condition is inherently deflationary, seeking to do more with less. Yet fashions come and go in economics just as surely as they do in music (if a George Formby revival is imminent, position accordingly). I think what the COVID-19 pandemic has done is fire the starting gun for outright fiscal dominance and a more Keynesian economic model where politicians attempt to close the output gap through a fiscal response.

Having spent the past decade and more trying to stimulate private sector borrowing by lowering rates (explicitly, via the base rate, and implicitly via bond market intervention), we see increasing signs that governments are throwing in the towel and deciding to expand borrowing themselves with massive new spending plans.

Whether it be the Biden infrastructure package, the UK government’s ‘levelling up’ strategy, or China once again giving up on attempts to rein in credit growth, fiscal is back (even the Germans seem likely to prove more amenable to looser fiscal policy going forward). The US Congressional Budget Office forecasts that 47% of new treasury issuance will be purchased by US Federal Reserve balance sheet expansion over the coming years, with forecast budget deficits of 5-6% of GDP every year from 2021-2030.

Central bankers have no exit strategy, despite what they aver. Indeed, the rate of increase in the Fed’s balance sheet is already starting to accelerate again. So massive is the quantum of the expansion in the monetary base that some estimates suggest the velocity of circulation will need to fall by around 60% to neutralise the impact on inflation all else being equal.

Across the Eurozone, the ECB is forecast to purchase more government debt this year than will be issued; that QE operations are being conducted in the secondary market is merely a cipher to avoid the impression of outright monetisation. The Chinese government is once again attempting to rein in credit growth, but the Chinese economy cannot sustainably generate what is deemed to be an acceptable level (c. 6%) of growth without expansion of fixed capital formation and further regional infrastructure projects. Already there are tentative signs of capitulation on this front once again.

Of course, policymakers have run policy easily for an extended period without an inflationary follow-through. Why is this time different? Because governments are expanding; monetary expansion is not going to sit on bank balance sheets but is going to be invested directly into the economy. Fiscal policy may not be enough to neutralise the inherently disinflationary impact of technology, for example, but it can neutralise this and the impact of excess savings in the private sector.

As government infrastructure projects expand, demand for materials is going to meet already tight supply conditions. Supply discipline in the materials sector has become structural, in part because management teams are scarred by the previous commodity bust but further because many of the world’s more easily accessible open or shallow-pit sources of metals have been exhausted.

And although the cure in energy markets for low prices used to be low prices, the dominance of ESG mandates and a blanket adherence to their strictures is setting up a squeeze in the energy market. Expansion of oil and gas supplies has ceased, and equity raises to fund exploration have become significantly harder.

Meanwhile, a recent paper highlighted that wind farm maintenance costs are likely to be far higher than anticipated when projects were greenlit. Nor is it just raw materials seeing supply squeezes, with tightness in the supply of key inputs such as semiconductors highlighted in recent months (leading to TSMC announcing they will be raising prices by 20%).

The market assumes that central bankers are independent actors committed to reining in inflation when necessary. It is not listening to what they are saying. Fed chairman Jay Powell’s comments on 10/02/2021, for instance, included that if wage inflation improved amongst the lowest earners after other segments (i.e. once the labour market was already tight), that this did not have an adverse impact on inflation, and that the Fed would target full employment. Perhaps most importantly, he noted that many of the benefits of a strong-labour market only arose towards the end of the previous expansion; the Fed is telling us they will run policy ‘hot’.

Even if the Federal Reserve wishes to tighten policy the USD’s dominant position as the global currency of trade settlement makes this hard for them to do, as we saw in both 2015 and 2018 when attempts to tighten policy at the margin (against the backdrop of strong domestic economic performance) caused ripples in the global economy that promptly caused them to reverse. The Eurozone economy remains stagnant and dependent on imported inflation easing nominal debt burdens which meagre organic growth simply cannot offset. Government expansion is likely to prove the only source of growth, and growth they have decided they must have.

As geopolitical tensions continue to mount between China and the West, expect further reshoring of businesses (as we discussed here). Even where China remains embedded into global supply chains, razor thin margins in China coupled with rising input costs and the challenges of food price inflation (preventing competitive devaluation) means costs will be passed on in the near term. Across the West, the government will not be the only one investing; the savings rate of the private sector will decline as companies are no longer able to rely on arbitraging labour costs in different jurisdictions to maintain competitive margins.

Anaemic capital expenditure rates will pick up, as will productivity as manufacturing is returned. Productivity rises typically beget wage rises, and with labour share of the economy low it will simply not be tenable in any major developed economy for wage inflation not to materialise as a corollary (with the possible exception of Japan). Already the US Bureau of Labour reports that survey results show that prospective employees naming the lowest wage they would be willing to accept for a new job in H1 2021 named an average wage 30% higher than their answer to the same survey in H1 2020, and 40% higher than H1 2019. Electoral necessity will mean that this will probably materialise most tangibly in those areas of the labour market with the greatest marginal propensity to consume. Wage inflation will set the stage for more sustained consumer price inflation.

In part, elevated margins in market leaders will take the hit, but companies further up the supply chain have typically been devastated and reduced to a level of subsistence production by monopsonistic practices. Yet the appointment of Lina Khan with bipartisan support to the FTC shows that rethinking antitrust law is in the political zeitgeist in the US (the Eurozone remains mired in thrall to oligopolistic multinationals, but will be forced to adapt or die).

Against this backdrop, we have to rethink the structure of our portfolios fundamentally. As the managers of Ruffer Investment Company (RICA) have highlighted, this likely heralds the death of the 60/40 portfolio and risk-parity models (inverted correlations between bonds and equity will turn positive). Commodity producers, like those held within BlackRock World Mining (BRWM) will see stronger pricing power and improving margins, whilst countries which benefit from improving terms of trade from rising global inflation will see secondary benefits. As we have seen in previous inflationary epochs, Latin America stands to benefit within the GEM space, and BlackRock Latin American (BRLA) should enjoy structural tailwinds. In this environment, the value rally has legs and country leadership changes. The UK and Japan stand to benefit amongst developed markets, and value-led strategies such as Aberforth Smaller Companies (ASL) and Miton UK MicroCap (MINI) stand to benefit. Yield curve control, as seen in the 1940s in the US, will cause real yields to decline further and further benefit precious metals, with mining companies such as those in Golden Prospect Precious Metals (GPM) the winners.

[1] Still, you’ve got to laugh.

The bond market is the truth – Thomas McMahon

‘Buy the rumour, sell the fact’ is a popular and useful investing adage. I would argue the recent high US CPI prints are the facts that should leave investors thinking about reducing their exposure to investments for an inflationary environment.

There was a lot of noise last year about the inflationary impact of the QE programs unleashed to handle the pandemic. This was reminiscent of the post-2007 period in which numerous managers and commentators fretted about inflation – even possible hyperinflation. The monetarists’ arguments were a bit more sophisticated in 2020 (after their warnings proved misguided last time), and distinguished money sent to support the banking system (not necessarily inflationary) from money injected directly into the economy (supposedly inflationary). However, I don’t think the recent high CPI prints reflect the truth of these analyses but simply base effects.

The US and global economy are recovering from a huge deflationary shock in which a large proportion of economic activity simply stopped. As activity restarts, prices have risen. It is true that we saw huge fiscal stimulus in the US and UK to support the economy, but these are time-limited, transitory phenomena.

The third round of direct stimulus payments under the CARES Act is filtering through, but the Biden administration has signalled this will be the last, with the focus turning to its economic recovery plan. While there have been all sorts of rumours and stories of companies finding it hard to hire workers for menial work, the alternative (living off government cheques) is coming to an end. US unemployment is c. 6%, roughly double its pre-pandemic level.

In other words, there is still slack in the labour market, and once stimulus payments run out, labour’s bargaining power doesn’t look strong. Although April saw strong wage growth in the US, the number was lower in May, and I expect may have peaked.

Biden’s economic recovery plan does imply huge amounts of fiscal expenditure. However, I would suggest that commodity prices reflect these expectations already. Copper rose roughly 56% from the beginning of November 2020 until peaking in May.

It is down around 9% since then. Palladium rose around 26% over the same period and is down 11% since its peak. What is important for inflation (a rate) is the rate of increase of prices, not the price level. While fiscal stimulus may mean prices remain at higher levels than in the past, and this may filter through to consumer prices in the short term, for inflation to remain high off the back of it requires expectations of demand to rise further from here.

A cynic, I would suggest political reality means expectations are more likely to decline as legislation passes through congress. The plan as it stands has already been described as more of a redistribution of unspent funds from previous packages by UBS’ chief economist Paul Donovan.

US wage inflation rolling over is significant. To get persistent inflation you require a persistent rise in input costs. This should ideally be wage inflation, as employees’ bargaining power increases with unemployment is low.

This is the inflation the Fed wants to see in the fulness of time. Its commitment to wait to see this (and therefore to look through inflation from other sources) is in my view simply a recognition that full employment is the most important of its two targets, and that it will not jeopardise that by responding to short-term inflationary impacts from the hugely disruptive pandemic period.

Persistent inflation could also come from a persistent rise in commodity prices such as we saw in the 1970s in the oil market thanks to the creation of OPEC and wars in the Middle East. This sort of inflation could easily accompany a weak economic period and would represent stagflation. I would suggest we may well see a very short period of stagflation as the current inflationary impulse subsides and government stimulus falls away.

However, over the long run the fundamentals for sustained persistent price rises aren’t there. This is reflected in long-term break-evens, which suggest bond investors do not see excessive inflation once the recovery period has settled down. 30-year break-evens are currently 2.33%, up to levels last seen in 2014 and almost perfectly in line with ten-year break-evens. In other words, the bond market thinks our current inflationary spike will be short-lived.

In the short term, one other important disinflationary force will be the ending of social distancing mandates. Social distancing was a key reason behind the sharp rise in shipping costs during the vaccine rally, which led to alarmist headlines about inflation.

Crews going ashore, exchanging members, the unavailability of ports and dry docks, all were affected by quarantine requirements and extra health and safety restrictions, and in a globalised economy would be expected to feed through to end consumer prices eventually. However, the extra costs required to keep businesses open are in the process of being removed.

The pace of the US’s reopening has surprised some – with even democratic states keen to end social distancing almost wholesale – and this will lead to cost savings which can help offset any residual inflation working through the system, and the inflationary impact of the ESG-related phenomena Callum refers to. In the UK we will get there too, with rumours suggesting the 19 July policy change will be radical and wide-ranging.

I won’t digress and expound on Friedman’s views on inflation. Suffice to say that ‘V’ is a very limited way to describe how money shifts around in the economy and in particular the banking system. It is true that monetary aggregates have increased once more. They have not led to inflation in the recent past, and there is no clear reason why they should now.

If I am right, and it is time to fade inflation expectations, then quality growth and technology could be areas to look to. If growth is likely to remain relatively subdued and inflation subsides close to central banks’ targets without radical rate rises, then quality growth companies could do well. And while numbers all look positive at the moment as economies open, soon we will have the consequences of the lockdowns to deal with economically, meaning the operating environment for companies may not be great once we have reopened for good.

This would support quality growth too – and we would argue a lot of technology is ‘quality’ by virtue of generating high and sustainable earnings of low incremental injections of capital. At the moment, a number of trusts in these spaces look cheap. Allianz Technology Trust (ATT) is trading on an 8.3% share price discount as of 24/06/2021 compared to a one-year average premium of 8.2%. Herald Investment Trust has had a wild ride, a discount of c. 20% at the start of 2020 narrowing to par in Q4 and widening back out to the current 17%. Monks’ discount of 2.2% is not wide in absolute terms, but three standard deviations below its one-year average 2.8% premium. I think quality growth trusts like Aberdeen Standard Asia Focus (discount 13.4%) and Scottish Oriental Smaller Companies(discount 10.3%) could also look interesting at this juncture.

Click to visit:

Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future results. The value of investments can fall as well as rise and you may get back less than you invested when you decide to sell your investments. It is strongly recommended that Independent financial advice should be taken before entering into any financial transaction.

The information provided on this website is not intended for distribution to, or use by, any person or entity in any jurisdiction or country where such distribution or use would be contrary to law or regulation or which would subject Kepler Partners LLP to any registration requirement within such jurisdiction or country. In particular, this website is exclusively for non-US Persons. Persons who access this information are required to inform themselves and to comply with any such restrictions.

The information contained in this website is not intended to constitute, and should not be construed as, investment advice. No representation or warranty, express or implied, is given by any person as to the accuracy or completeness of the information and no responsibility or liability is accepted for the accuracy or sufficiency of any of the information, for any errors, omissions or misstatements, negligent or otherwise. Any views and opinions, whilst given in good faith, are subject to change without notice.

This is not an official confirmation of terms and is not a recommendation, offer or solicitation to buy or sell or take any action in relation to any investment mentioned herein. Any prices or quotations contained herein are indicative only.

Kepler Partners LLP (including its partners, employees and representatives) or a connected person may have positions in or options on the securities detailed in this report, and may buy, sell or offer to purchase or sell such securities from time to time, but will at all times be subject to restrictions imposed by the firm’s internal rules. A copy of the firm’s Conflict of Interest policy is available on request.

PLEASE SEE ALSO OUR TERMS AND CONDITIONS

Kepler Partners LLP is authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority (FRN 480590), registered in England and Wales at 9/10 Savile Row, London W1S 3PF with registered number OC334771.

Commentary » Investment trusts Commentary » Investment trusts Latest » Latest » Take control of your finances commentary

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.