Nov

2022

How to secure our energy future

DIY Investor

11 November 2022

And it’s not the greener firms that will save us – by Savvas Savouri

To be an economist one cannot also be a diplomat, in as much as to be truly economically objective, one risks making statements which will very often prove objectionable and open oneself up to confrontation. The following statement falls squarely into the category of, ‘You will not want to hear this but is it perfectly true all the same’, so here goes.

The upwards cost of energy shock we have experienced is almost entirely of our own making and we must now quickly find the energy to fix things. Had we approached things differently in advance of what has hit Ukraine, we would not have faced the scale of the energy cost shock we have. As to the nature of our self-inflicted suffering, this falls under two quite different headings:

Our pretence that the market in which we buy our energy is as competitively supplied as the one in which we buy our groceries.

The delusion that we could afford to reject investing in more varied domestic forms of energy supply than ‘pure renewables’, and somehow avoid our bills rising and avoid moreover being hostage to global energy price shocks.

So to be clear, there was an ‘energy crisis’ coming to the UK even had the invasion of Ukraine not happened. What the invasion of Ukraine has merely done is bring forward what was going to befall us. Let me explore our twin delusions in slightly more detail, starting with the second.

For years now we have been restricting how we make and store energy. True, we have been doing so in efforts to protect our environment. No less true is we have given little or no attention to how restricting home-grown forms of energy supply has made us extremely vulnerable to what would hit us when something like the invasion of Ukraine strikes, viz the cost of oil and gas shooting up. And to be clear, such events are far from uncommon.

‘One can even point to how the global shock to our energy costs is playing a key role in domestic politics’

Let us reflect back to 1973 and 1979, when wars both triggered significant rises in the price of oil and nasty shocks to the UK economy. Remarkably, we seem to have learnt nothing from these shock experiences concerning our energy security.

As we witness our fuel bills rising sharply, this in turn is forcing up interest rates and mortgage costs. These cost of living pressures are in no small part fuelling demands for higher pay and triggering strike action when awards are not deemed sufficient; in turn interrupting supply chains and adding upwards pressure to prices.

One can even point to how the global shock to our energy costs is playing a key role in domestic politics. And this is the whole point. While almost the whole world is experiencing an element of what we are, it is obvious that the lowest degree of energy cost pain is being felt by nations with the greatest in-house energy capacity.

The reality is, had we pursued fracking to extract shale gas, returned to coal, commissioned far more nuclear capacity and added, not reduced, gas storage facilities, the UK would not be in the painful energy pricing position it has been in the past and indeed now finds itself. There is also the fact that in demonising the UK’s oil and gas firms and demanding companies disinvest from them ‘unless and until they go green’, we have not only undermined their investment in new capacity, but their keeping up existing capacity across oil and gas fields in British waters.

Let me now turn to the first delusion. We have long lived with the myth that we can chose between a myriad of energy suppliers so as to shop around for the best price deal. The reality has always been that our energy derives not from a market with so many suppliers that we are the price makers, but from an oligopoly. The suppliers are simply intermediaries between consumers of energy and the few firms originating electricity and gas. What unfolded post the spike in wholesale energy costs was as inevitable as it was brutal.

While there will come a moment the combatants in Ukraine wake up to the fact they need to cease fire, this alone will not return us to the energy market pricing status quo ante bellum. Moreover, while the elevated price of ingredients in producing energy such as oil, gas and coal will encourage increased supply of all these, this too will not be enough to return pricing to its status quo ante bellum. Furthermore, while slowing industrial activity in the US and across Europe will ease energy consumption, this too will not return to its status quo ante bellum.

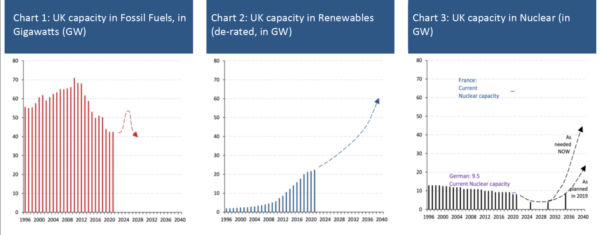

If we wish to escape the energy-pricing nightmare we are in, we need to wake up to the fact that in addition to all forms of renewable energy (chart 2), we need to do at least one of the following: extract shale gas and open cast coal (chart 1), commission more nuclear capacity (chart 3) and/or add gas storage facilities.

The sharp rise in energy costs we have experienced must make us all reappraise the way we ‘trade off’ what is best economically and what is imperative for environmental good. For too long these have been mistakenly assumed to be in conflict. Here though is a paradox to ponder. What if we pursue environmental good with such uncompromising dogma that we impair our economic environment? Well, the recession induced cannot fail to bring about environmental harm. After all, the firms most likely to survive a recession will be those who have been most tardy in their enviro-ambitions; if, that is, they had any at all.

What most certainly cannot work together is caring for our environment whilst also dealing with recessions induced because we are hostage to geo-political shocks that reduce global energy supplies. To best insulate the UK, it needs to secure its own energy supply; something which it simply cannot do solely from renewables, unless of course we accept the UK economy is much smaller and much poorer.

Lastly, we need to remove from the short-term political cycle our long-term energy plans; remove energy from being managed in a way deemed populist by politicians, to being governed by what is practical. Just as we have depolarised monetary policy, we should now do the same with how we strategise UK energy policy.

Published by our friends at:

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.