Feb

2023

Here comes the sun

DIY Investor

10 February 2023

Our analysis suggests renewable energy should be at the core of a well balanced portfolio…by Alan Ray

We recently attended a City power lunch with an old colleague, which among other things got us thinking about labels and categorisation. As we opened our ‘Pret a Manger’ sandwiches and admired the excellent view of the roadworks on Old Broad Street, we got talking about markets and during the conversation the phrases ‘core infrastructure’ and ‘renewables’ came up a couple of times. Afterwards, we thought “are those really useful labels anymore? And is investor behaviour influenced by the implication contained in the word ‘core’?”.

This word doesn’t appear in any formal sector name, but ‘core infrastructure’ is a very common phrase, both in speech and in investor presentations. When one thinks about it, ‘core’ is quite a powerful adjective. This is particularly so when it’s used in the same sentence as ‘renewables’, which isn’t awarded automatically that same adjective and so by implication is non-core, or possibly even ‘satellite’, as they might say in fund management circles.

This begs the question why we routinely imply that a key part of the infrastructure sector, energy, which all the other bits of infrastructure are quite literally plugged into, is in some way a satellite? After all, no one ever talks about BP or Shell as being satellite portfolio stocks.

Apart from noticing our correct use of the word ‘literally’, readers may have noticed the easy trick we played in the last sentence, substituting the word ‘energy’ for ‘renewables’. Isn’t it interesting how changing a word here or there can change perception? We should say for the record that the AIC’s formal sector classification is ‘Renewable Energy Infrastructure’, which contains all the right words. But in our experience, the labels used in conversations and investor presentations are different and carry implications.

We think there a few reasons why investors think and speak this way. The first is just a question of who got out of the gate first and built a presence in investors’ minds and portfolios. Almost 20 years ago the first listed infrastructure funds began to appear on the London Stock Exchange.

Pitching themselves as boring, predictable investments for risk-averse investors, they slowly built up momentum and, collectively, became an impressive capital-raising machine and an important source of capital for UK plc’s infrastructure. Remember that for every £1 of traditional listed infrastructure equity, there is potentially another £9 of debt of different seniorities, so although the listed sector may appear small in the context of the size of the UK’s infrastructure, it provides that ‘first loss’ tranche that helps secure substantial amounts debt.

Renewables’ investment trusts came along a little bit later and had many shared characteristics, but also some differences which meant that, at the time, it was fair enough to categorise them as being a little less core.

First, the technology was far from unproven, but was certainly evolving. One simple example is asset life. All those years ago, there wasn’t enough real-world data to know what the useful life of a solar panel was, and so estimates that went into calculating net asset values were very conservative. As time has passed, the expected lives of even older solar panels have been extended as more data has been gathered about their performance over time.

Longer asset lives mean that net asset values are less volatile. Today, wind and solar operators are able to model, with surprising and somewhat fascinating accuracy, the different weather patterns and diurnal rhythms of their assets. If we may digress slightly with what the younger generation call a ‘fun fact’, as recently as 1840, railway timetables reflected the local solar time for each town along the line, with Bristol some 11 minutes ahead of London due to its longitude.

Since the railway clock was the one that people would use to set their own clocks, people’s lives were lived on local solar time. Once the Great Western Railway between London and the West Country was established, noted engineer Isambard Kingdom Brunel decided to bring this complex and unwieldy system to order.

Timetables were printed in London time, which probably led to many people missing, or being exceptionally early, for their trains for a while. But, of course, solar panels never got that particular memo and continue to operate on solar time, which, even in a relatively small country like the UK, varies enough to provide diversification for the grid depending on where panels are sited. As we say, this is something of a fun fact but we’ll come back to the subject of diversification in a couple of paragraphs.

The second reason was that there was a perception of higher political risk, as renewable energy policy was less well-formed in the UK. Political risk is ever-present, of course, and raised its head in 2022 when it initially appeared that renewables would be heavily penalised by an undiscriminating energy tax. But, as we’ll come to see later on, the renewable energy sector has real scale these days.

This is making it much harder in reality to deal them an unfair political blow. A week is a long time in politics and it will remain so. However, now that ‘net zero’ is enshrined in law, it is uncontentious to say that renewable energy is here to stay. In some circles that was a controversial statement ten years ago…

This brings us on to a third possible reason, which we’ve already alluded to: technology. Renewable energy is, we should acknowledge, an emotive topic and attracts a lot of opinions. We are looking at it through the lens of investment but we can see why it’s easy to disappear down the rabbit holes of discussing the next big technology that’s going to ‘solve’ things.

For example, we can’t remember a time in our lives when tidal power wasn’t about to solve the UK’s energy problems, what with the Bristol Channel and the River Severn together having one of the world’s largest tidal ranges. Maybe this will eventually become part of the energy equation one day, but the slow progress made over many decades doesn’t suggest it’s an easy task.

Taking a different example, we know that when the energy storage funds Gore Street Energy Storage Fund (GSF), Gresham House Energy Storage (GRID) and, more recently, Harmony Energy Income Trust (HEIT) raised capital from investors, a great deal of time was spent discussing what technology could replace lithium-ion batteries as the primary technology in energy storage. This is an absolutely massive rabbit hole if one cares to go down it.

The most likely thing to happen is incremental improvement brought on by more efficient manufacturing. Breakthroughs do happen and, in fact, lithium-ion batteries were a bit of a breakthrough when the technology was first developed in the 1980s. It wasn’t until the 21st century that the technology become commercially viable, which is a very helpful fact to keep in mind when one is down the rabbit hole.

Our favourite is the old mining trains that move concrete blocks up and down a mountain pass somewhere in the US, ascending when there is power to be stored and descending when it’s time to release the energy using gravity. Venture capital money should be going into new technologies, of course, but most are not even close to be in the realm of core infrastructure.

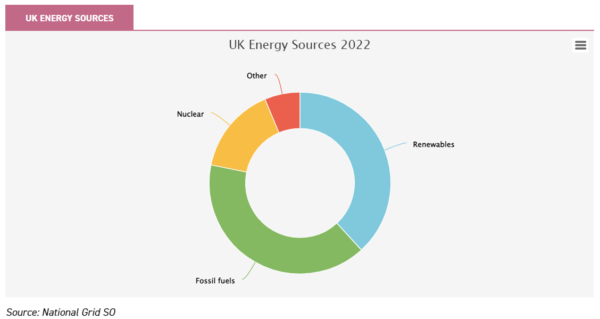

All this means that some investors are still waiting for the breakthrough and, as a consequence, existing technology is perceived as being exposed to a high risk of being superseded. The chart below is an illustration of what we think the real breakthrough is. This is the UK’s energy mix in 2022, sourced from National Grid System Operator statistics.

Two conclusions we can draw from this are that the technology that can move the dial already exists and has been deployed on an industrial scale, and that there’s plenty more to be done. Or, from an investor’s point of view, plenty more to go for. To be absolutely clear, the overwhelming majority of that ‘renewables’ category is made up of off and on-shore wind and solar or, in other words, existing technology.

One might be thinking “that’s all very well, but haven’t you forgotten about EVs and the fact that the electricity that will be needed to support them will just overwhelm the grid?”. We invite anyone thinking of going down the internet’s rabbit hole on this topic to take a packed lunch, as there’s plenty of opinion on this one.

More time-pressed readers should think back to the last time a whisper of a “petrol shortage” went around. What happens? Everyone rushes to fill up their tanks and, as a result, in a very short space of time there’s – that’s right, a petrol shortage. The UK’s petrol stations don’t carry enough fuel to fill up every car on the road simultaneously and EVs are no different.

Average daily car journeys in the UK of about 20 miles don’t result in an EV having to recharge fully every night. Down the rabbit hole, one can find the maths that says that the grid will be overwhelmed by everyone charging their EV at the same time.

The UK regulator, Ofgem, is planning for a 20% – 30% expansion in energy capacity to cope with the growth of EVs. Precision forecasting over a couple of decades isn’t easy, but we aren’t talking about an unachievable target that existing technology can’t take on. Again, this seems achievable with the industrial scale of renewable technologies we already have.

One final issue that might have held renewables back from being considered ‘core’ is diversification. But a quick look across the sector shows that one can build a portfolio of onshore wind, offshore wind, wind subsidized by ROCs, wind exposed entirely to the market price, rooftop solar, ground-mounted solar, solar in southern Europe, Scandinavian hydropower, energy storage in the United States or the Republic of Ireland, as well as things such as power networks, construction risk and co-location of energy generation and storage.

We’ve probably missed a few but, hopefully, the point is made: the sector isn’t exposed to a single jurisdiction, subsidy or technology. Let’s take a few specific examples.

Greencoat UK Wind (UKW) has £4.5bn invested in a portfolio of wind energy electricity-generating assets across the UK, split approximately one third offshore and two thirds onshore . Onshore assets are located in every part of the UK, including Northern Ireland, which is on a different grid to the rest of the UK.

UKW takes revenues from traditional ROC subsidies, from more current CFD contracts and from merchant sources. It takes its technology from several turbine manufacturers and owns assets with a wide spread of ages. It’s not focussed, therefore, on one revenue stream, one weather pattern or even on one national grid. It’s a significant player in the UK market and, as such, has a voice in the industry that can help influence energy policy.

The Renewables Infrastructure Group (TRIG) has £3.2bn invested across offshore wind, onshore wind and solar, and is beginning to invest in storage. It has assets across several northern European countries – approximately 60% in the UK, but also in Sweden, Germany and France, as well as some assets in Spain. Therefore, it is exposed to several different technologies, and to multiple jurisdictions with different revenue stacks and to multiple electricity grids. Again, TRIG is a significant player in the UK with influence.

Energy storage is a very important enabling technology that the UK-listed market has woken up to, with three listed funds. We highlight Harmony Energy Income (HEIT) as we notice that even as the financial and general press was full of stories about the failure of nascent battery manufacturer Britishvolt, quite separately Harmony Energy quietly put out a press release noting its stake in the largest operational energy storage facility in Europe, based in Yorkshire, which received very little coverage.

Renewable Energy Infrastructure funds, as a group, are now trading at a discount to net asset value, averaging c. 4%. This followed a year when investors were right to fret about political risk. This risk seems to have abated, but in the meantime those discounts to net asset value provide some breathing space.

It is also worth noting that, generally speaking, discount rates to calculate net asset values are rather higher than for traditional, let’s not say ‘core’, infrastructure funds. One can view this as an indication that net asset values are, therefore, likely to be more volatile, but one can also view that as a potential opportunity for the risk premium to come down over time as the asset class continues to evolve.

Listed investment funds aren’t, on their own, going to raise enough capital to build the renewable energy infrastructure that the UK will need to complete its transition. But they are a key signal to investors that the UK is an important destination for renewable energy investment.

We read the press like everyone else and know that the latest story is about the difficulty of attracting investment to the UK because the US has the Green New Deal and the EU is seen as a friendlier environment for investment, and so on. These may be true today and no one can be complacent. But again, look at what has already been achieved almost without anyone noticing and what is left to be done, and the opportunity this creates for an investor.

We think that the time to stop casually referring to renewables as if they were non-core has come. They are a core part of the UK’s infrastructure and economy and they deserve to be a core part of any infrastructure portfolio.

Disclaimer

This is not substantive investment research or a research recommendation, as it does not constitute substantive research or analysis. This material should be considered as general market commentary.

Alternative investments Commentary » Alternative investments Latest » Brokers Commentary » Commentary » Investment trusts Commentary » Investment trusts Latest » Latest » Mutual funds Commentary

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.