Dec

2020

Can you teach an old dog new tricks?

DIY Investor

15 December 2020

This is not substantive investment research or a research recommendation, as it does not constitute substantive research or analysis. This material should be considered as general market commentary.

Cheap companies in Japan are drowning in what cheap companies elsewhere would kill for: buckets of cash…

Cheap companies in Japan are drowning in what cheap companies elsewhere would kill for: buckets of cash…

Growth has outperformed value in Japan this year, as it has for quite some time. However, there are distinctive qualities to growth and value in Japan which mean they each offer something different to a portfolio.

In particular, value investing in Japan offers a potentially more exciting opportunity set with a catalyst for recovery that doesn’t rely on a global shift of interest rate regime or economic environment.

Something new

Fund managers like to refer to the ‘new Japan’. This incorporates growth sectors like information technology, but tries to capture something more than this.

Japan’s demographic decline and low-growth trap have led to developments in the economy and society which may end up anticipating the route the developed world goes down post-COVID.

For example, Japan has some of the world’s leading companies in robotics which offer solutions to companies suffering from the decline in the working age population in that country, but which also offer ways to increase margins for international peers.

Meanwhile the Japanese market also contains many companies which may once have been growth companies, but which have failed to keep up with the pace of change.

Either that, or they have begun to feel the pinch from inefficient corporate structures and balance sheets. These companies are sometimes referred to as ‘old Japan’.

In our view there are many interesting opportunities to be found in these areas, in particular given the reform programme of the current government, which could unlock the value and growth potential in unwieldy and undervalued companies.

Growth in the new but value in the old?

In Japan as elsewhere, high-growth companies have been bid up to expensive valuations. For example, the portfolio of JPMorgan Japanese Investment Trust (JFJ) – which we view as a typical example of a ‘new Japan’ trust – trades on a current P/E of 39x, compared to the 17x of the TOPIX Index.

In theory such a premium can be justified by higher growth which should lead to more attractive PEG ratios. However, given that future growth is estimated, if forecasted growth trajectories fail to materialize then stock prices could take a major hit.

The graph below shows the returns from the growth and value sectors in Japan over the past three years. The outperformance of growth began to accelerate last year and has kicked into a higher gear after the emergence of the pandemic.

‘New Japan’ companies typically have the other stylistic characteristics of a growth stock: high expected earnings growth, low dividends and often higher return on equity (ROE).

Japan’s history of low interest rates, with the Japanese ten-year bonds yielding near to 0% for the last three years, has served to further boost valuations of ‘new Japan’.

‘Old Japan’ on the other hand is more akin to a value or income sector, with comparatively higher dividend yields, lower valuations and stronger but crucially cash-heavy balance sheets.

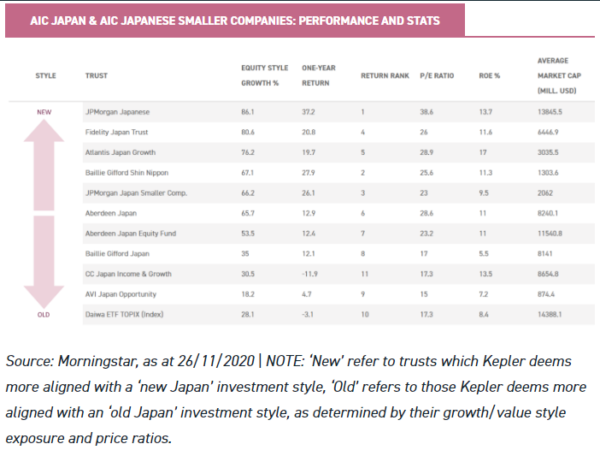

The breakdown of the sector returns over the past year presented below illustrates how the top-performing portfolios in the AIC Japan and AIC Japanese Smaller Companies sectors have strongly growth-tilted portfolios with higher P/Es and generally higher ROEs.

Like many global investment strategies, the best-performing Japanese trusts over the year had much of their performance driven by healthcare, pharmaceuticals and internet services, sectors often associated with ‘new Japan’.

This is something clearly demonstrated by JPMorgan Japanese Investment Trust, the best-performing trust over the last year. Two of the biggest contributors to its return have been M3, a provider of healthcare software, and MonotaRO, an online retailer of industrial supply products. We updated our note on the trust in recent weeks.

What is not included in this table is harder to quantify, and that is strong balance sheets. These are one of the interesting features of ‘old Japan’, which we think make it a much more interesting sector to search in for value ideas.

Show me the cash

Traditionally Japanese companies have been seen to have poor corporate governance, typically lacking independent board members and having under utilised balance sheets.

Companies have traditionally had more complex structures designed to protect the interests of a few major shareholders and long-term managers. This is typically achieved through such companies holding large portions of the equity of their competition, a practice termed keiretsu in Japan.

This allows them to resist industry change or active shareholders as well as insulating them from market movements and takeover attempts. The practice of keiretsu is particularly common in Japan’s manufacturing and industrial sectors, mainstays of ‘old Japan’ and the value sector.

Family-owned companies are also a similar problem, with issues around the alignment of minority shareholder interests with the family owners’, as well as creating huge headaches when deciding on leadership succession.

However, former prime minister Shinzo Abe put corporate governance issues at the heart of his programme in 2014, with a series of policies aimed at improving ROE and growth as well as attracting foreign investors through improvements in the quality of corporate governance.

The greatest scope for change is clearly found within ‘old Japan’, given their often convoluted structures and governance issues (as outlined above).

These changes are being implemented through policies such as the Companies Act, which requires the inclusion of at least one independent director, as well as requiring the improvement of the quality of communication to shareholders and disclosures around remuneration.

There are also regulatory initiatives such as the Corporate Governance Code introduced in 2015, which aims to tackle the impact of cross-holdings and poor RoE. There is also the Stewardship Code, which commits investors to engagement with companies on these issues.

This means there is a clear catalyst for the unlocking of the value in these balance sheets, which is at the heart of the strategy of AVI Japan Opportunity Trust (AJOT).

Despite growth being in favour since it was launched, AJOT has managed to outperform the MSCI Japan Small Cap Index, illustrating the powerful potential in this secular trend which we think could accelerate if there is any regime change from growth to value.

Another factor which could be in favour of ‘old Japan’ – or the value sectors – is the increasingly crowded nature of the ‘new Japan’ trade. While the impact of COVID-19 has certainly improved the outlook of ‘new Japan’, this has not translated into a diverse set of opportunities.

While ‘new Japan’ strategies do tend to have a high active share against the index, with JPMorgan Japanese Investment Trust having a 95% active share against the TOPIX, there are an increasingly smaller number of companies present in the top ten of most ‘new Japan’ strategies.

International investors will find that names which were once relatively unknown to them are now present in many ‘new Japan’ strategies in both the open and closed-ended space: names like Keyence, Hoya, Bengo4.com, MonotaRO and GMO Payment Gateway.

While the outperformance of ‘new Japan’ strategies is increasingly attractive, investors need to be aware of the increasing concentration around not only the trends which are driving performance, but also the underlying companies held. This could increasingly lead to a trade-off between their diversification and performance.

A third factor in their favour is that ‘old Japan’ companies are often more in control of their destiny. With their resilient balance sheets, operational scale and often diverse sources of revenue, ‘old Japan’ companies are typically better placed to weather high-growth ‘new Japan’ peers or possibly also their Western value cousins.

Value investors within the FTSE 100, for example, are typically taking on exposure to the domestic retail banks , cyclical materials, and energy sectors, with the latter also facing strong structural headwinds.

Value investors in Japan have more chances to invest in industrial or other names which may have growth potential but which we view as having been structurally underusing it thanks to poor or inefficient corporate governance.

It is also worth noting that many large Japanese companies function as conglomerates, owning multiple subsidiaries each with their own diverse sources of revenue.

As a result, ‘old Japan’ companies can offer investors diversity of sources of revenue in a way some ‘new Japan’ names or ex-Japan value stocks cannot.

This may be one of the reasons Warren Buffett took up positions in the main Japanese trading houses or conglomerates, with their complicated webs of cross-holdings and multiple sources of revenues.

Finally, the high levels of cash on the balance sheets mean there is the potential for dividend growth in ‘old Japan’ stocks.

By tapping into these cash piles, many ‘old Japan’ companies have been able to operate in 2020 without resorting to the dividend cuts or employee furloughs of their Western peers; something many UK income investors would be envious of, given the recent dividend cuts from the major yielders.

The Nikkei 225 Dividend Index, which reflects the aggregate dividends paid from the constituents of the Nikkei 225, is only 9% below its pre-pandemic all-time high, clearly preferable to the estimated 30% fall in dividends that UK and European investors face in 2020.

This is a point that has been reasserted by Richard Aston, the manager of the CC Japan Income & Growth Trust (CCJI), who has been impressed by the resilience of many Japanese companies during this period, having seen only a handful of dividend cuts across his portfolio. CCJI offers a 3.3% yield and entered the year with reserves 0.9x last year’s full dividend and a distributable special reserve.

More of the same?

That’s not to say that the run for ‘new Japan’ stocks has necessarily had its day. COVID-19 has been an accelerator of many of the trends underpinning ‘new Japan’ and the growth theme globally.

In fact, COVID-19 can be seen as a huge boost for a number of ‘new Japan’ names, with the obvious immediate beneficiaries being remote working and electronic payments. Bengo4.com is an excellent example of a COVID-19 winner which is also helping to solve some of ‘old Japan’s’ archaic business practices.

Bengo4.com is a software company that offers CloudSign, a cloud-based document-signing service, which solves one of the biggest headaches caused by working from home in Japan: the inability to physically sign documents.

Business practices in Japan require the physical stamp of a hanko, a personalised seal that often replaces signatures, on nearly all major documentation. COVID-19 has seen an immediate change in this practice (which dates back over 1,000 years), with in-person signings becoming less palatable, having been replaced by Bengo4.com’s technology which enables remote validation.

Furthermore, the inefficiencies in the traditional value areas of ‘old Japan’ have opened up new avenues within ‘new Japan’, with increasing opportunities for M&A firms to tackle these inefficiencies through corporate actions.

This has benefitted companies like Nihon M&A, which has seen its share price more than triple over five years and is a top-ten holding of Baillie Gifford Shin Nippon (BGS).

However, given the reliance of high-growth companies in Japan on prevalent trends, they are susceptible to their reversal. For example, sectors like recruitment services within Japan are exposed to reform of Japan’s stringent immigration policies, something which was slowly whittled away under Shinzo Abe.

Further easing of immigration may dilute the professional applicant pool which recruitment services rely heavily upon, reducing their ability to charge a premium for their services. There are also themes within the new economy that Japanese companies are struggling to capitalise on from the outset.

While there have been winners (like Rakuten) in Japanese e-commerce, Nicholas Weindling, the manager of JPMorgan Japanese Investment Trust, has highlighted the difficulty many companies are having when competing with Amazon Japan, which remains the biggest online retailer in Japan in terms of digital traffic.

Aberdeen Japan Investment Trust (AJIT). AJIT tends to straddle both themes, thanks to the managers’ focus on quality growth and sensitivity to valuations. By focussing primarily on the quality factor, they are able arguably to capture some of the best names within ‘old’ and ‘new Japan’, such as Keyence (an automation leader and a ‘new Japan’ company) and Shin-Etsu (Japan’s largest chemicals manufacturer, and very much ‘old Japan’).

Conclusion

‘New Japan’ has in our opinion trumped ‘old Japan’ over the last few years, reflected by its outperformance against ‘old Japan’.

While investors in ‘new Japan’ could be confident in the continuation of many of the trends supporting it (especially given the shake-up COVID-19 has brought to Japan), investors in ‘old Japan’ may also have an interesting future.

In fact, the environment for value investing in Japan may be more attractive than in the rest of the world thanks to the specific characteristics of the Japanese market discussed above.

We think exposure both to high-growth trends and to the secular improvement in Japanese corporate governance and unlocking of corporate balance sheets could be attractive at the moment, particularly in what is likely to be sluggish global growth in the recovery from the current crisis.

Click to visit:

Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future results. The value of investments can fall as well as rise and you may get back less than you invested when you decide to sell your investments. It is strongly recommended that Independent financial advice should be taken before entering into any financial transaction.

The information provided on this website is not intended for distribution to, or use by, any person or entity in any jurisdiction or country where such distribution or use would be contrary to law or regulation or which would subject Kepler Partners LLP to any registration requirement within such jurisdiction or country. In particular, this website is exclusively for non-US Persons. Persons who access this information are required to inform themselves and to comply with any such restrictions.

The information contained in this website is not intended to constitute, and should not be construed as, investment advice. No representation or warranty, express or implied, is given by any person as to the accuracy or completeness of the information and no responsibility or liability is accepted for the accuracy or sufficiency of any of the information, for any errors, omissions or misstatements, negligent or otherwise. Any views and opinions, whilst given in good faith, are subject to change without notice.

This is not an official confirmation of terms and is not a recommendation, offer or solicitation to buy or sell or take any action in relation to any investment mentioned herein. Any prices or quotations contained herein are indicative only.

Kepler Partners LLP (including its partners, employees and representatives) or a connected person may have positions in or options on the securities detailed in this report, and may buy, sell or offer to purchase or sell such securities from time to time, but will at all times be subject to restrictions imposed by the firm’s internal rules. A copy of the firm’s Conflict of Interest policy is available on request.

Commentary » Investment trusts Commentary » Investment trusts Latest » Latest » Mutual funds Commentary

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.