Sep

2020

Bull in the Chinese market?

DIY Investor

29 September 2020

This is not substantive investment research or a research recommendation, as it does not constitute substantive research or analysis. This material should be considered as general market commentary.

The Chinese stock market has been a notable winner thus far in 2020. Should investors stay the course, or take profits?

Russia may, according to Churchill, have been a “riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma”, but China is scarcely more accessible for many of us in the West today.

Yet as the world’s second largest economy, an increasingly large financial market and a dominant component of what is, to most investors, a core emerging market allocation in their portfolios, China compels us to have a view on its economy and markets.

At the start of the year if you had heard that:

- China would see geopolitical tensions ramp up with multiple neighbours; and globally with the US, Australia and the UK, amongst others

- A global pandemic would emerge from deep in the heart of China

- The global economy would enter an almost unprecedentedly sharp contraction

- The Yangtze Delta would be devastated by floods, putting strain on the Three Gorges Dam and necessitating the evacuation of tens of millions of citizens

- Peak to trough losses in global equities would be c. 33% (MSCI ACWI World, as measured in USD)

- The trading status of the main source of foreign capital for the Chinese market (Hong Kong) was under threat

You may reasonably have concluded it was best to eschew a weighting to the Chinese market.

Yet in doing so, you would have missed out on participating in a market that has generated YTD returns of c. 15.2% in USD terms as of 17/09/2020 (Source: Yardeni); second only to the healthcare/pharmaceuticals dominated (at c. 40% sector market weight) Danish stock market.

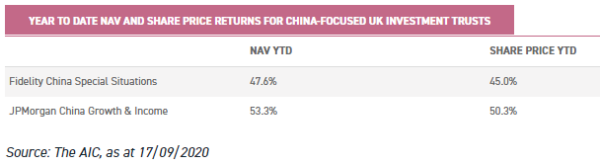

Even better returns would have been enjoyed by UK investors in either of the two specialist Chinese market investment trusts currently available, as can be seen in the table below.

This is before we even consider the positive contribution Chinese stocks have made to numerous global portfolios, such as Scottish Mortgage and Manchester & London.

Drivers of returns are debatable, with some highlighting relatively strong headline GDP numbers from the Chinese economy as driving fundamental support for long-term structural growth opportunities.

Conversely bears might argue that the move upwards in prices is a reflection of a policy attempt to rally confidence in a system that is creaking, and ultimately unsustainable.

As tensions continue to ratchet up between China and its neighbours, as well as the US – is it too late to join this market rally? Or does this story remain compelling in the near term?

Bull – Enter the Dragon | Thomas McMahon

JPMorgan have estimated that Tencent can annualise earnings growth of c. 22% p.a. for the coming five years – that is c. 170% total growth in five years – such is the open-door they are pushing on.

Of course investors globally appreciate this story: JPM’s bullish forecast for Tencent assumes a valuation derating over this period, reducing returns by around c. 6% p.a. This figure still leaves an annualised return of around 16% for shareholders on the table if correct.

Tencent, along with Alibaba, is a hugely dominant player in the Chinese stock market.

Of course the market writ large cannot be reasonably expected to generate these levels of growth, but if true it would be regrettable to stand aside and not seek to participate in this single stock potential irrespective of your macroeconomic outlook.

Indeed the state backing these global technology players enjoy should leave them unimpeded by any government attempts to cut them down to size for the foreseeable future, so long as they continue to toe the political line.

China has numerous companies which offer the potential to benefit from a rising consumer class and domestic economic activity.

Remember that, on a per capita basis, China remains very much a middle-income country at this time. In my view, there is still plenty of ground to be made up on developed economies, and attempts to do so will likely create huge stock opportunities.

Of course this is under the auspices of far more interventionist government policy than we are used to in the West.

This approach cuts both ways, but the control the government has been able to exercise over the banking system, for example, has been beneficial in smoothing the economic downturn the Chinese economy has faced in 2020.

By forcing an increase in investment spending domestically in the initial phase of the economic contraction, economic activity remained more dynamic than may have otherwise been the case – even if the ultimate pay-off to these investments may be poor.

Accordingly, as global economies normalised somewhat in Q2 2020, the Chinese export sector has proven well-placed to benefit from rebounding global trade, generating domestic profits and boosting consumer confidence.

Following on from this topic it is interesting that, following a rebound in manufacturing activity in Q2, retail sales returned to year-on-year growth in August 2020.

I think the feed through to investor confidence is likely to remain tangible, and can further boost a stock market already tacitly being supported by easy monetary policy and credit creation.

This avenue comes with an inflation risk, and the destruction of much of the country’s domestic agricultural production in the recent Yangtze floods will only exacerbate rampant food price inflation.

However the government seems to me to prefer to address this issue through the use of strategic reserves, and so it seems likely to continue to let credit grow and build domestic supply chains.

Undoubtedly geopolitical risks have to be considered, but these are very much already in the news and in the minds of investors.

Over the longer term reshoring of western supply chains, or simply disinvestments from Chinese production hubs, will probably represent a challenge to the domestic Chinese economy, if it has not yet managed to migrate to a consumption-led economy.

However this strategy seems unlikely to be in the imminent offing, given the challenges facing the global economy and the damage already done to supply chains.

Simply put, I would expect there to be a symbiotic need between China and the rest of the world that will perpetuate the status quo for the near future. As a result attendant boosts from capital flows should follow.

Having seen debt levels rise, and with a strenuous debt burden already in place, I expect a renewed push for raising capital through equity in the Chinese market.

Whilst individual holdings may face dilution, this will require buoyant market conditions to generally be tenable.

The authorities retain many levers yet to boost this through margin lending conditions, credit volumes or even tacit instructions to financial market participants.

The Chinese market and economy do face some challenges however. There is no doubt about that. Yet capital allocators are aware of this, and there is little sign of complacency as to the risks.

In the Western world, where economies of scale have arguably played out and there is little room for significant further corporate consolidation, capital allocators will no doubt look enviously at growth rates in emerging market economies and companies.

With a strong framework seemingly already in place for this, I think China stands to be amongst the primary initial beneficiaries.

It may be too soon, however, for investors in China-focused trusts such as JPMorgan China Growth & Income (JCGI) to be looking to take profits yet, while other, more generalist Asian equity trusts continue to offer attractive exposure to this market. For example the managers of JPMorgan Asia Growth & Income (JAGI) note that they continue to observe strong growth across their portfolio, even in the challenging market environment of 2020 thus far. Furthermore they believe that they can look to compound these growth rates over time.

Bear – For Whom the Bill Tolls | Callum Stokeld

You do not invest in Chinese equities. At best, you trade them. At least that is my working assumption. An investment implies a long-term holding made on the assumption that you will ultimately have access to future cash flows. To explain my brief interlude into pedantry, let us digress briefly.

Remember that for around 2,700 years ‘Tianxia’ (‘all under heaven’) drove the Chinese state’s cultural understanding of the world, with the emperor having been divinely appointed all lands via the ‘Mandate of Heaven’.

Of course, for practical reasons, the emperor could not rule all lands himself, and tributaries and other subordinated states would derive their power from the tacit acceptance of the emperor.

The concept of dealing with other nation states as if they were themselves sovereign and should thus be dealt with as equals, based upon Westphalian sovereignty, was an alien concept (in theory if not de facto) which was ultimately forced upon the Qianlong emperor.

The current leadership of the Chinese Communist Party has been fairly explicit in its desire to return China to its perceived rightful place in the global order – i.e. at the top.

This situation will not, in my view, simply involve taking an existing template and rewriting it in Mandarin. Dominant nations need to be seen to deal with problems and relationships on their own terms.

Tianxia isn’t making an explicit comeback. But I think China will view foreign shareholders very much seen through this broad prism.

Why else is the primary method for western capital to buy Chinese shares through overseas-listed variable interest entities which, in the worst-case scenario, afford holders little of the same rights they would have as shareholders?

As systematically depriving all overseas holders of VIEs of ownership rights in the underlying businesses would likely cut China off from all global capital markets, there is little realistic threat here. But it should be remembered that there is nonetheless a threat.

More immediately pertinent to your interests as a shareholder are, in my view, opacity – note the raft of proposed delistings from US markets by companies, when it was suggested they comply with US transparency rules on corporate governance – and the entire political system.

Currently Chinese companies are obliged to make reference to the interests of the Chinese Communist Party in their articles of association. They now must also have board members fulfilling the same function.

China is an intensely political system and, despite the pushback in some of western academia, a fundamentally Marxist one.

Every interaction is seen through the prism of politics and, in a Foucauldian twist, power structures. Do you think that, when push comes to shove, your interests as a shareholder will be represented in capital allocation?

So why would you ever rent these stocks, let alone own them?

Paradoxically it seems, I would suggest that weaker economic activity will often be a stimulus to the market. Why? Because of the nature of credit and money creation in China.

Credit is created essentially by central diktat; there is not generally a nudge here, such as through interest rates, but an instruction that credit should rise by x amount.

Credit needs to find a home, and banks creating it need to find someone to take it off their hands.

In times of plentiful domestic and global demand, it may not be hard to find takers seeking to finance corporate expansion and investment. Similarly if wages are buoyant the housing market stands to be a beneficiary, as households access favourable lending opportunities to buy property.

When activity is weaker and there is less demand from corporates, household demand becomes more important. Yet house prices have been buoyant and very elevated, relative to incomes in many major cities for quite some time – and this is typed by a resident of London.

Stocks have stood in as beneficiaries over much of 2020: credit was created and needed an outlet. There is little appetite for mass house price rises.

Chinese property developer Evergrande has announced a price war, and policy makers no doubt remember reports of riots from householders in negative equity around five years ago.

Economic activity domestically was focused on investment, it’s true, but much of this was national and local government-led and focused on public infrastructure.

With global demand deficient, there was no appetite amongst domestic producers to build up capacity.

So the market benefitted. Credit growth accelerated even as leading and real-time indicators showed economic activity contracting.

Ample liquidity and easy money bid the stock market higher, the market rerated, and margin debt rose to the highest level since January 2016.

Meanwhile profits margins are actually fairly elevated at an index level relative to their own history, according to Yardeni Research. Admittedly, they are not exactly wide margins on a global basis.

But the index is perennially held back on this scope by a raft of state-owned enterprises. Relative to its own history, the Chinese market has higher profit margins than at any other time in the past 15 years.

Margins tend to be fairly mean-reverting and, with domestic supply creation having outpaced demand growth, I do not expect many firms to have pricing power.

Those that likely do retain pricing power are seeing themselves cut out of the growth markets they crave the most. Tokenistic gestures from the US government are more likely in the near future, as they seek to boost President Trump’s re-election bid.

But the die is cast, and Sino-scepticism is in the US political zeitgeist. The US is not alone however. China’s political leadership is proving to be an issue with certain companies, such as the Swedish clothing retailer H&M which recently curtailed production contracts in Xinjiang on the grounds of political concerns.

Growth assumptions, and the ability of leading Chinese companies to convert revenues to free cash flow, are surely more at risk than the lofty valuations attached to these companies suggests?

Economic activity is recovering so I expect credit creation will likely move towards financing this in future, and marginal rate of flows to the stock market will fall.

We are already seeing this trend unfold somewhat. Since economic activity noticeably started picking up in Q2 2020 market momentum has been dying, with the Chinese market peaking YTD on 06/07/2020, and this will hardly entice back domestic retail investors buying on margin.

Yet global economic normalisation, or at least continued recovery, should continue to benefit domestic economic activity in China. BlackRock World Mining’s (BRWM) investments in commodity companies, makes it look to me like a more attractive way to play any global economic recovery.

Downside risk seems more appropriately priced, supply and cost discipline within the underlying companies should see marginal profitability rise with any rise in the pertinent commodity prices, and you carry noticeably less geopolitical attention.

The Chinese economy probably needs a global economic recovery. Shareholders in Chinese companies will not be amongst the main the beneficiaries in my opinion.

Of course many investors look to structurally allocate to the Asia-Pacific region. In such circumstances a trust such as Aberdeen Standard Asia Focus (AAS) could continue to offer exposure to a region that does continue to display strong economic trends, but via an investment trust which is consistently underweight to the Chinese market.

Click to visit:

Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future results. The value of investments can fall as well as rise and you may get back less than you invested when you decide to sell your investments. It is strongly recommended that Independent financial advice should be taken before entering into any financial transaction.

The information provided on this website is not intended for distribution to, or use by, any person or entity in any jurisdiction or country where such distribution or use would be contrary to law or regulation or which would subject Kepler Partners LLP to any registration requirement within such jurisdiction or country. In particular, this website is exclusively for non-US Persons. Persons who access this information are required to inform themselves and to comply with any such restrictions.

The information contained in this website is not intended to constitute, and should not be construed as, investment advice. No representation or warranty, express or implied, is given by any person as to the accuracy or completeness of the information and no responsibility or liability is accepted for the accuracy or sufficiency of any of the information, for any errors, omissions or misstatements, negligent or otherwise. Any views and opinions, whilst given in good faith, are subject to change without notice.

This is not an official confirmation of terms and is not a recommendation, offer or solicitation to buy or sell or take any action in relation to any investment mentioned herein. Any prices or quotations contained herein are indicative only.

Kepler Partners LLP (including its partners, employees and representatives) or a connected person may have positions in or options on the securities detailed in this report, and may buy, sell or offer to purchase or sell such securities from time to time, but will at all times be subject to restrictions imposed by the firm’s internal rules. A copy of the firm’s Conflict of Interest policy is available on request.

Commentary » Investment trusts Commentary » Investment trusts Latest » Latest » Mutual funds Commentary

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.