Apr

2022

Are overseas takeovers a threat to the UK stock market?

DIY Investor

10 April 2022

M&A is a global trend but, unlike elsewhere, most UK companies have gone to overseas buyers. Why, and should we care? asks Duncan Lamont

M&A is a global trend but, unlike elsewhere, most UK companies have gone to overseas buyers. Why, and should we care? asks Duncan Lamont

A third of the major companies on the UK stock market a decade ago* have since vanished, with more than half going to overseas buyers.

Almost all were bought by or merged with another company. This in itself is not unusual – our previous analysis of the US stock market came to a similar conclusion, albeit over a slightly different timescale.

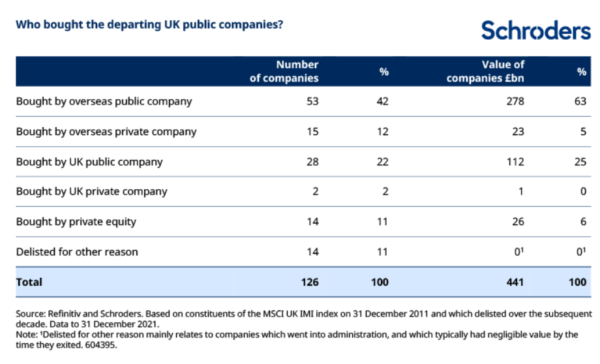

But what is striking for the UK is that it’s been overseas buyers who have been snapping them up – 54% by number and almost 70% by value have gone overseas, mostly to foreign public companies. These include famous companies such as SABMiller, Shire, Sky, and ARM Holdings. The biggest buyers by far have been US public companies, followed by Canadians.

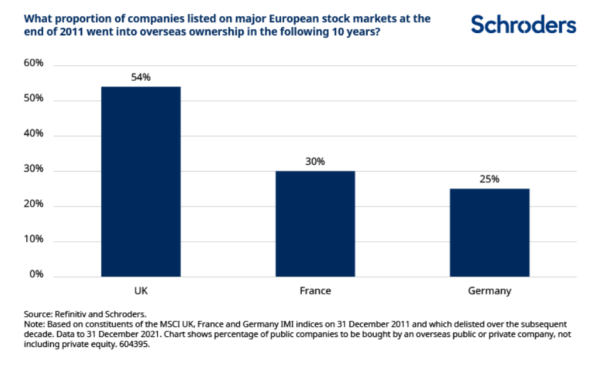

This is in stark contrast to the US where the biggest buyers have been other US public companies. US stock market investors have retained an interest in their ongoing prospects, only as part of another public company, just not on a stand-alone basis. Not so, for the UK.

It is also different to what has happened in continental European markets. Only 30% of French companies to delist, and 25% of German ones, were bought by an overseas company (mostly other European ones).

A relatively small proportion of UK companies to de-list, 11% by number and 6% by value, have fallen into private equity hands. Interestingly, private equity has played a more prominent role in German takeovers than UK ones.

All in all, of the £441 billion of companies in this cohort to depart the UK market, £326 billion, 75%, ended up overseas or under private equity ownership (which was also mostly overseas).

Only £112 billion was bought by another company on the UK stock market. And just over £1 billion by private UK businesses.

Fourteen companies departed for other reasons, mainly going into administration. Their value was typically negligible by the time they exited.

To sell or not to sell, that is the question

The need for a buyer to offer a takeover premium over the share price provides a juicy incentive for shareholders to sell. In our data set, the median company to be bought/merged returned 38% in the 12-months before de-listing (a period which would typically capture any share price-response to takeover/merger activity). It outperformed its sector by an impressive 25% over this period.

It’s not hard to see why shareholders can be tempted by an approach. But the risk is that it puts short term profit ahead of longer term potential gain. These buyers are not offering a premium out of charity. It is because they believe that ultimately the business will be worth much more to them.

Now this is often partly because of synergies – when you combine two businesses there is often potential for cost cutting as shared common functions can be consolidated e.g. finance departments.

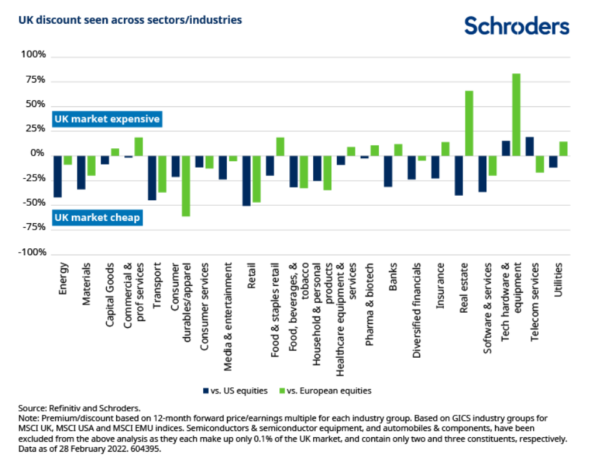

But it can also be because of opportunities to grow the business. Or because the buyers thinks it’s undervalued. The UK stock market has been trading at an ever-wider valuation discount to global peers. This is true for the vast majority of industries. So it cannot just be blamed on the UK having a larger exposure to energy and materials companies, and lower to technology, than the high-flying US.

What looks to be more behind it is a lack of appetite from global investors to invest in the UK market full-stop. Not helped by Brexit-uncertainty, the asset class has seen 31% cumulative outflows since June 2016, according to Refinitiv Lipper data.

Potential buyers are assessing that the valuation of some companies is being adversely affected by them being listed in London. And that their true, unimpaired, value may be higher.

A threat to a thriving equity market

A thriving UK stock market is important, not just for investors and companies, but also for the UK economy and society.

From the companies it finances, to the people working in the markets directly, to the companies and services which support them, to the taxes the industry contributes, which pay for vital public services. While this covers much more than the stock market alone, it is an important piece of the jigsaw.

And when the number of companies on the UK main market has fallen in 23 of the last 25 years, and stands at only 42% of its level from 25 years ago, then this has the potential to be a worrying development.

Companies being bought isn’t a bad thing as such. It can be a sign of a healthy and dynamic market and economy. But too few companies have sought to join the UK stock market, to replace the ones departing.

These takeovers may be cutting off potential future corporate success stories at the knees. When people ask, why there are not more world-beating companies being built in the UK and listed in London (don’t get me wrong they do exist, just fewer than we might want), one answer may be that they sell out too soon.

And an inability to nurture companies to sufficient scale, whatever the reason, means that when buyers do come shopping, overseas companies have more clout to do the deals. This may explain why we are unable to replicate the US outcome, where it is other US companies that have been the biggest buyers of their public companies.

There are still more than 1,100 companies in total on the UK main market (a wider universe than those analysed above) . And 2021 was one of the two years in the past 25 when that number did increase. So the UK is not in a danger zone…yet at least.

But markets operate on confidence. Success is self-fulfilling. If a country is known as a place where companies can raise money, more are drawn to it. The reverse is also true. If the UK comes to be viewed as a market in decline, whatever the reason, then a self-reinforcing decline could set in.

To ensure the UK thrives as a listings venue, it is important to look at both why too few companies have been listing and also why so many have been delisting. Emphasis so far has been on the former, such as the encouraging measures set out in the Hill review. The latter should not be forgotten.

Should companies care?

It would be possible for companies to raise money without a thriving UK stock market. They could borrow from a bank, as many already do. And, if they need to raise equity they could do so on an overseas stock exchange, or from private equity.

Moreover, many of the large international companies listed in London have no binding need to call the UK home. They could just as easily be listed elsewhere. This may be part of the problem.

The UK market may be partly a victim of its own past success in attracting overseas companies to list in London. With weaker UK roots and closer operational ties to countries outside of the UK, they are more likely to appeal to companies in those countries, and multinational buyers.

This is particularly the case for the energy and materials companies which London successfully attracted in the 2000s. 30% of the companies to delist were in one of these two industry groups, much higher than the 22% of companies those sectors made up.

But away from these large companies, a dig down the capitalisation scale unearths a deep well of more domestically-oriented small and mid-cap companies. They may be familiar (ish) names to people in the UK but many would find it harder to raise money overseas, where they would be more unknown quantities. They would have much more to lose if the UK market lost its status (with knock-on impacts on entrepreneurship etc).

Should investors care?

If you can earn a healthy return boost when a company in your portfolio is taken over then what’s the problem?

And, in a world of global investing, does it matter if a company lists on the US stock market rather than the UK, as the UK’s most successful technology company, ARM Holdings, looks set to do? It would be no less accessible, for institutions and UK individual investors alike. It might have mattered in the past but not today.

The strongest argument why investors might be doing themselves a disservice is if, in accepting a takeover bid at a premium to today’s share price, they may be missing out on even higher gains in future.

This is contentious. Previous research we have carried out found that a majority of takeovers involve a transfer of value from buying to selling shareholders. Almost 60% acquirors of US public companies went on to underperform their industry group in the one to three years after a takeover. It’s not possible to do a counter-factual and assess what would have happened if they hadn’t made the acquisition. Or whether the acquired company would have been more successful had it stayed independent.

But it’s certainly not immediately obvious that investors would make more money if they said no to more takeover bids. They might – but it would depend on the individual company, situation, and time frame. Each needs to be assessed on its own merits.

What are the lessons?

In the near term, UK equity investors should welcome renewed M&A interest in UK-listed companies. It could help narrow the valuation discount which has dogged the market in recent years.

Longer term the bigger losers from a drip, drip, drip of UK listed companies to overseas buyers are not likely to be investors, but the UK economy at large, something that policymakers and politicians should not lose focus of.

*Companies within the MSCI UK investible Markets Index at end 2011

Important information

This communication is marketing material. The views and opinions contained herein are those of the named author(s) on this page, and may not necessarily represent views expressed or reflected in other Schroders communications, strategies or funds.

This document is intended to be for information purposes only and it is not intended as promotional material in any respect. The material is not intended as an offer or solicitation for the purchase or sale of any financial instrument. The material is not intended to provide, and should not be relied on for, accounting, legal or tax advice, or investment recommendations. Information herein is believed to be reliable but Schroder Investment Management Ltd (Schroders) does not warrant its completeness or accuracy.

The data has been sourced by Schroders and should be independently verified before further publication or use. No responsibility can be accepted for error of fact or opinion. This does not exclude or restrict any duty or liability that Schroders has to its customers under the Financial Services and Markets Act 2000 (as amended from time to time) or any other regulatory system. Reliance should not be placed on the views and information in the document when taking individual investment and/or strategic decisions.

Past Performance is not a guide to future performance. The value of investments and the income from them may go down as well as up and investors may not get back the amounts originally invested. Exchange rate changes may cause the value of any overseas investments to rise or fall.

Any sectors, securities, regions or countries shown above are for illustrative purposes only and are not to be considered a recommendation to buy or sell.

The forecasts included should not be relied upon, are not guaranteed and are provided only as at the date of issue. Our forecasts are based on our own assumptions which may change. Forecasts and assumptions may be affected by external economic or other factors.

Issued by Schroder Unit Trusts Limited, 1 London Wall Place, London EC2Y 5AU. Registered Number 4191730 England. Authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.