Aug

2018

Why is growth so slow? An old debate about money has some clues

DIY Investor

3 August 2018

The Great Moderation, the period of stable growth between the early-90s and late-2000s, has been back underway again for several years, but with noticeably less momentum.

In the US, UK and Eurozone, annual rates of GDP growth of 3% and 4% have been replaced by 1% and 2%

Austerity takes some of the blame, but a larger slice of underperformance can be put down to changes in the way money is produced.

That banks create money when they lend has been a source of controversy among British economists since at least the 18th century. A constant feature of these money debates is the Currency School view – that the business of saving and lending should be separate from the business of money creation.

Banks tend to over-lend in a boom and contract lending in a bust, making the money supply pro-cyclical and the economic cycle more extreme.

Throughout its history the Bank of England has attempted to control the amount of credit and money created by the banking system through various means such as interest rate changes and bank regulation.

Currency School thinking was behind Switzerland’s recent vote on ‘vollgeld’. The Swiss ended up rejecting it, allowing banks to continue to create electronic money.

Vollgeld aside, the Currency School has scored a bigger victory in recent times. For some time now, banks have been required to hold greater levels of capital for each loan they make to businesses — rules formalised in the new regulatory framework known as Basel III, but which have been in place in some form or other since around 2008.

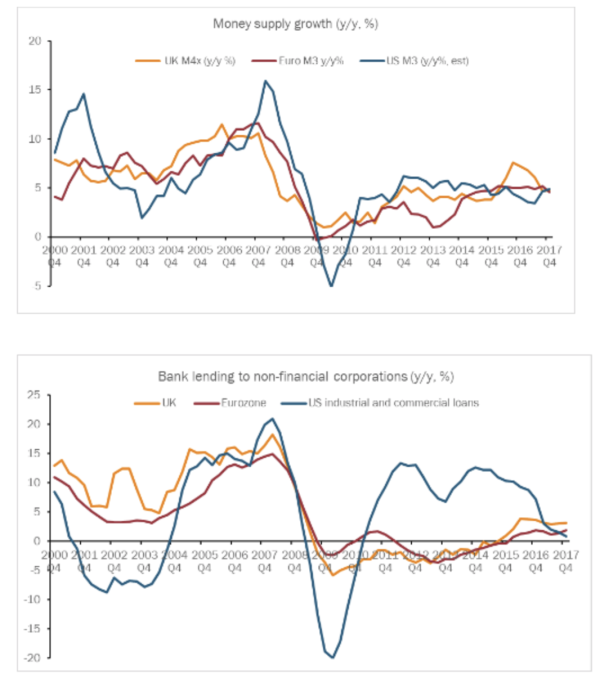

These rules make lending more expensive for banks. The result has been a substantial decline in the growth rate of bank lending to businesses, reducing the growth rate of the money supply. The charts below show the money supply figures from the US, Eurozone and UK, which are published by their respective central banks.

They have various motorway-sounding names because definitions of money vary across borders and times. Central banks also have their own preferences; the US stopped publishing M3 in 2006, but it is still the best option and can be closely estimated. Bank lending to non-financial private sector companies (NFCs) is also shown.

Unable to borrow all they need from banks, companies have plugged their financing gap by selling shares and bonds (bonds account for the vast majority of this). Some bonds are bought by banks, but most go to investments funds – pension funds, insurance funds, sovereign wealth funds and separate funds designed to invest on their behalf.

In contrast to a bank loan, selling a bond to an investment fund does not create money. Investment funds have always been a major source of financing for companies in the US, accounting for a much larger share of corporate borrowing. Yet it has traditionally been less common in Europe due to the existence of a well-established banking system.

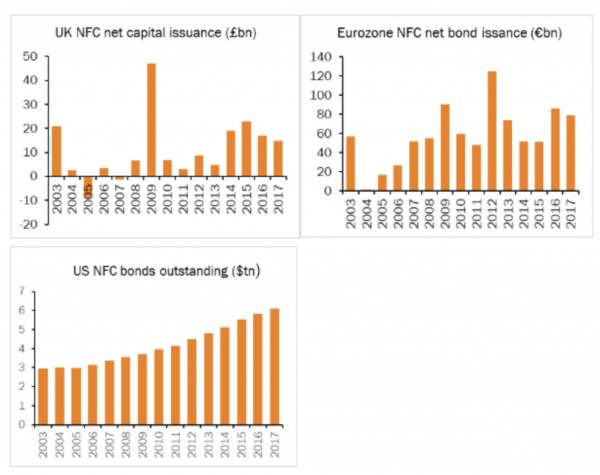

The following charts show that since 2008, while bank lending has been weak, non-financial companies have been successfully raising cash by issuing bonds and stocks. Again, the figures are presented differently by the respective central banks, but the message is the same – since the financial crisis, bank borrowing has been largely replaced by issuing bonds and shares to funds.

These figures also understate the case because over the past decade there has been rapid growth in so-called direct lending – a loan between one or two investment funds and a company. This type of lending is not included but is highly prevalent. Leveraged buyouts are now mostly funded by direct lenders rather than banks, in contrast to the pre-crisis years.

The switch from banks to funds has led to a lower rate of growth of the money supply. It may improve financial stability by reducing the amount money supply growth moves around in a boom-bust cycle. However, the fact it was introduced abruptly at a time when the economy was operating well below potential has restricted the ability of the economy to bounce back.

Money shortages such as this typically end up weighing on spending. The link between money and spending is complicated, but in general there cannot be a sustained increase in one without a similar increase in the other. Spending in money terms (or nominal GDP, or GDP not adjusted for inflation) has been over one percentage point per year lower in the US and UK since the recession compared with the Great Moderation, and two percentage points lower in the Eurozone.

Today’s central bankers aren’t fussed by these trends. Their organisations produce money and lending figures such as those shown above, but monetary policy makers tend to ignore them. Instead, their focus has been on the labour market, and as a result they have been wrongfooted over the last several years with low unemployment by itself failing to generate price and wage inflation.

Even if unemployment is low, wages and prices won’t gain much momentum while spending is restrained by monetary factors. The Bank of England and US Federal Reserve are determined to continue raising interest rates, while the European Central Bank is planning on winding down its quantitative easing. If they continue with their plans, they will find themselves wrongfooted again.

Article originally published by CapX.

Chris Papadopoullos is a financial journalist based in the City of London.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.