May

2025

Why cash is riskier than stock market investing

DIY Investor

18 May 2025

We need an entire rethink of how we talk about risk – by Duncan Lamont

Holding cash is riskier than investing in the stock market. This might seem a bold claim, given the gyrations of markets in recent weeks, but it’s one of my most strongly held beliefs. The data backs it up. And recent market declines don’t invalidate it.

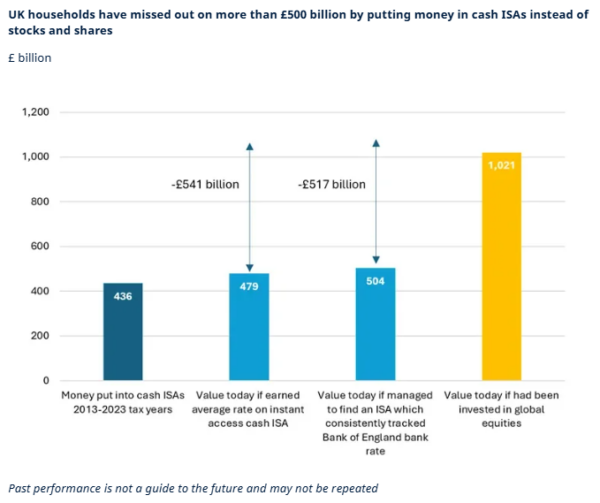

The passion for cash in their ISAs has left UK households more than £500 billion worse off than if they’d invested in the stock market in the 10 tax years to April 2023. This is based on what those savings would be worth in the present day (as at 30 April 2025).

Think what a difference that could have made, to individuals and the UK economy. It’s equivalent to nearly 20% of UK GDP. Individuals could also have spent some of that additional wealth on goods and services in the economy. Some would even have been used to back UK plc.

UK households have missed out on more than £500 billion by putting money in cash ISAs instead of stocks and shares

Past performance is not a guide to the future and may not be repeated

ISA subscriptions are assumed to have been invested at the average market level in each tax year and/or to have earned the average cash ISA rate/Bank of England bank rate in each tax year. Global equities are MSCI World index, total returns terms in GBP. Source: Cash ISA subscription amounts from HMRC, ISA rates and bank rate from Bank of England, MSCI World returns from LSEG Datastream. Data to 30 April 2025.

As an investment industry, we talk about risk a lot. But we frequently fail to explain in plain enough English what this means, nor that it means different things to different people. But it’s worse than that. The way that we, regulators, and everyone else talks about risk, with a myopic focus on the risk of any short-term fall in value, often fails to emphasise the real one that matters most to the people we’re supposed to be serving: the risk that they will be unable to achieve their financial goals.

The fetishisation of cash must stop. We need an entire cultural shift in how we talk about risk.

Let’s get this out of the way first

The topic of cash savings and the debate over potential changes to the cash ISA rules generate strong opinions.

Cash certainly has a role to play. It can be the most suitable place to put your money when your time horizon is short and/or absolute certainty is the top priority. To give a personal example, when I was actively looking for a property as a first-time buyer, I went all-in on cash. The risk to me of my deposit falling in value was greater than the potential upside if it grew a bit more over the six months it took to find and complete on a purchase.

More generally, when to comes to building financial resilience, a rainy-day cash fund should be a priority. Research has shown that that having a £1,000 buffer cuts your chances of falling into debt by almost a half. Sadly, 24% of UK adults have less than this. Schroders is fully behind all efforts to help more people build up such a cash buffer. Nothing in this article is intended to diminish the value of cash in this sense.

But what is worth challenging is the cultural inertia which leads people to stay mostly or entirely in cash once they have larger amounts of savings or a longer-term horizon.

Few advocates for investing

“The value of your investments may go down as well as up and you may not get back what you originally invested.” This is what individuals see when they investigate opening a stocks and shares ISA. The emphasis is on the downside. For the wary, it can only add to their worries.

We also have people with large followings in the print and online media who regularly talk about and promote the benefits of investing in a cash ISA, while being silent on stocks and shares. In some particularly disappointing cases, they even actively discourage their use. Where investing does get a mention, the focus is invariably on the day-to-day risk and bumpiness of the stock market, with no mention of potential upside.

This may be because of worries about personal liability/consequences if their readers were to invest and lose money. And of course there have been shameful episodes where investment risk has not been properly explained in the past. But that doesn’t make it the right thing to urge everyone to steer clear of the stock market for ever – in fact it’s a disservice.

Is it any wonder we don’t have an investing culture in the UK? This also applies to Europe. Every message that ordinary savers receive focuses on the risk of losing money. We are obsessed with risk disclaimers and reckless, feckless, and frankly irresponsible risk avoidance. There is no personal accountability. People think it is the regulator’s job to stop them from losing money, a view shared by many politicians. There are few loud enough voices shouting in opposition: we have got this all wrong.

Reframing risk

The real risk for most people is not the risk of losing money in the short run but the risk of not achieving your long-run goals, be they a comfortable retirement, house purchase, providing financial support to your children, or simply making sure your savings keep pace with inflation.

This is the risk of not taking enough risk.

The problem with cash

Cash is not risk free. £10,000 under the mattress 10 years ago will still be £10,000 today. The problem is that, because of inflation, you won’t be able to buy as much with that anymore. £10,000 worth of goods and services at the end of 2014 would have cost you around £13,500 at the end of 20241.

Had you put it in a cash ISA which paid interest in line with the Bank of England bank rate (most actually pay a lot less) you’d now be on about £11,500. More, but still not great. Cash rates have fallen short of inflation so you’d still have to cut back what you spent it on. Cash deposits have a dreadful track record of beating inflation in the long run. So is that cash ISA really “risk free”?

Maybe regulators should insist that a disclaimer pops up whenever someone puts money in a cash ISA: the value of cash savings has not kept pace with inflation in the past, may not keep pace with inflation in the future, and may mean you are unable to achieve your financial goals

Inflation is a risk.

The risk of not taking enough risk

Consider two alternatives. In one, you contribute X% of your salary a month and it gets invested in the stock market (a debate about what X should be is too much of a rabbit hole to go down here). The market goes up, it goes down but, in the long run, it is projected that you have a high likelihood of being able to retire aged 65 with enough money to afford a comfortable retirement.

In scenario two, you are worried that the stock market is too risky so instead plump for something “low risk”. You sleep more easily at night. But, because your savings won’t grow by as much, it is projected that you will need to keep working well into your 70s until you will have saved enough to be able to retire.

Which option appeals more now? Which is really riskier?

Or what if you’re saving for a deposit for your first home? The value of the average house in the UK increased from around £177,000 to £268,000 in the 10 years to the end of 2024. £10,000 in savings 10 years ago would have been worth 5.6% of the average house, a good step towards the magic 10% typically needed for a deposit. Had you put it in a cash ISA paying the Bank of England bank rate and watched it creep up to £11,500, it would now only be worth 3.7% of the average house. To get back to 5.6% you’d need to find an extra £3,700 (5.6% of £268,000 = 15,200 = 11,500 + 3,700, all figures rounded to the nearest £100). Or you may have to downgrade your homebuying expectations.

Not taking enough risk is a risk. People need to be more aware of the trade-offs.

The stock market is risky in the short run but less so in the long run

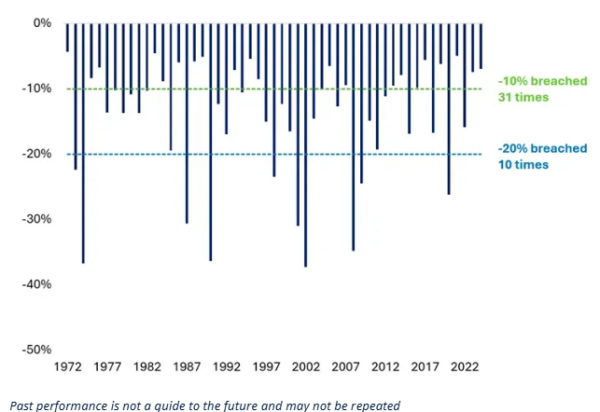

It is absolutely the case that investing in the stock market involves risk, in terms of potential for your investments to fall in value. Over the past 53 years, the global stock market has fallen by at least 10% in 31 of them, for sterling investors. This kind of thing happens in more years than not. 20% declines have happened roughly once every five years. Again, not an unusual occurrence.

But the trade-off is that, even allowing for these unpleasant slumps, the market has been a fantastic wealth generator for investors. Over this period overall, the global stock market has returned 11.4% a year, much more than the 4.8% rate of inflation.

10%+ falls happen in more years than not

Biggest stock market falls in each of the past 53 calendar years, MSCI World (GBP)

Past performance is not a guide to the future and may not be repeated

Source: LSEG Datastream and Schroders. Data to 31 December 2024 for MSCI World index in GBP terms

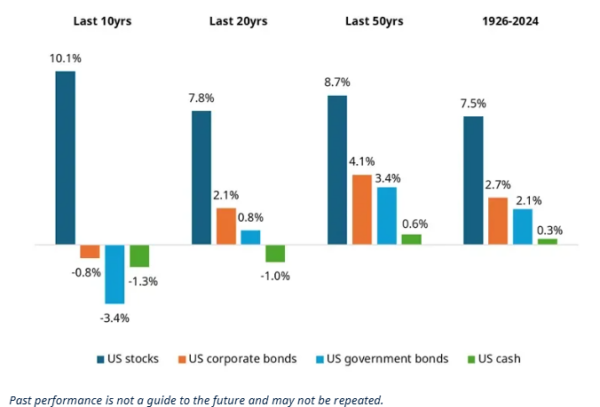

We can use look even further back using data on the US stock market and then the results are even clearer.

There is always a reason to worry but, in the long-run, stocks have beaten bonds which have beaten cash

US asset returns in excess of inflation 1926-2024

Past performance is not a guide to the future and may not be repeated.

Data to December 2024. 1926-2023: stocks represented by Ibbotson® SBBI® US Large-Cap Stocks, Corporate bonds by Ibbotson® SBBI® US Long-term Corporate Bonds, Government bonds by Ibbotson® SBBI® US Long-term Government Bonds, and Cash by Ibbotson® US (30-day) Treasury Bills. For 2024, an alternative index has had to be used for government bonds as Morningstar has halted data updates and production for the SBBI Indices. The ICE BofA 10+ Year US Treasury Index has been chosen for consistency. Source: Morningstar Direct, accessed via CFA institute, LSEG DataStream, ICE Data Indices, and Schroders

So yes, the stock market ride can be bumpy. But when you see this happen, don’t be spooked. It’s entirely normal. It is the price of the entry ticket for the long-term gains that the stock market has the power to deliver.

The chances of being able to achieve your financial goals would have been much higher if you invested in the stock market than if you parked your money in cash. It is less risky than cash when viewed through this lens.

It’s not even just that the stock market has beaten cash in the long run, it also has a much better track record of doing so over every reasonable investment horizon. The stock market has been less risky than cash in terms of likelihood of beating inflation. And the longer you invested for, the more the odds would have shifted in your favour. There have been no 20-year periods in our analysis when stocks lost money in inflation-adjusted terms.

Equities have been less risky than cash when it comes to delivering long-term inflation-beating returns

Percentage of time periods where US stocks and cash have beaten inflation 1926-2024

Past performance is not a guide to future performance and may not be repeated.

Source: Stocks represented by Ibbotson® SBBI® US Large-Cap Stocks, Cash by Ibbotson® US (30-day) Treasury Bills. Data to December 2024. Morningstar Direct, accessed via CFA institute and Schroders.

Losing money over the long run can never be ruled out entirely and would clearly be very painful if it happened to you. However, it is also a very rare occurrence.

In contrast, while cash may seem safer, the chances of its value being eroded by inflation are much higher.

A call to action

We need to change the way we talk about risk. It should be framed in terms of the risk that an individual can or cannot meet their financial goals. That is ultimately what matters. Heavy handed regulation needs to change. To that end, it has been encouraging to read that the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) explicitly recognises and backs such change).

Stock market investing needs a PR campaign.

People’s eyes need to be opened to the risk of sitting in cash.

The scale of the cultural shift required should not be underestimated. Old habits die hard. Sticks, such as changes to the ISA rules, may have a role. But people shouldn’t be forced to invest in the stock market. It would be far better if they do it because the realisation hits home about its amazing power to help them build wealth in the long run. And that, when viewed through that lens, it is cash that is the riskier place to put your savings.

1Based on the increase in CPI inflation over this period. The basket of goods and services in CPI is designed to be representative of consumer spending habits.

Please remember that the value of investments and the income from them may go down as well as up and investors may not get back the amounts originally invested.

This marketing material is for professional clients or advisers only. This site is not suitable for retail clients.

Issued by Schroder Unit Trusts Limited, 1 London Wall Place, London EC2Y 5AU. Registered Number 4191730 England.

For illustrative purposes only and does not constitute a recommendation to invest in the above-mentioned security / sector / country.

Schroder Unit Trusts Limited is an authorised corporate director, authorised unit trust manager and an ISA plan manager, and is authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.