Aug

2021

60/40 and other dinosaurs

DIY Investor

5 August 2021

A simple practical step to take your portfolio from the 1990s into the 2020s…

A simple practical step to take your portfolio from the 1990s into the 2020s…

This is not substantive investment research or a research recommendation, as it does not constitute substantive research or analysis. This material should be considered as general market commentary.

Over the decades, investors’ ideas about how to build the perfect investment portfolio have evolved. Large independent pension fund investors have typically led the way, with consultants and smaller pension funds following, and then discretionary private client wealth managers followed by individual retail investors echoing trends as they trickle down.

Markowitz is identified as the architect of modern portfolio theory and, to an extent, over time investors have been working with and adapting this theme to their portfolios. In the 1970s, perhaps a function of the high interest rates available at the time, many institutional and pension investors still focussed on fixed income.

In the 1980s many of these investors started investing in domestic equities, and the 60/40 equity and bond split within portfolios became more common, as investors recognised the diversification benefits that the two asset classes brought to a portfolio when combined. The 1990s saw further diversification, and international equity investing became mainstream. In the new century, institutions started to further diversify portfolios, adding investments in alternative asset classes such as private equity, hedge funds, real estate, and other alternative or illiquid assets.

Through the looking glass

The history of the investment trust sector has in some ways echoed these developments. In the ‘80s and ‘90s new investment trusts were launched to capitalise on ‘new markets’ such as Europe, Asia and Emerging Markets, with institutions being enthusiastic supporters. The discounts of the years that followed can partly be attributed to these same institutions realising that they could invest directly or through managed accounts in the same areas, at lower cost given the size of their mandates.

Similarly, the booming listed hedge fund sector in the mid-2000’s came on the back of the experience many institutional investors had of investing in Cayman based hedge funds in the late ‘90s and early 2000’s. Trusts continue to launch, enabling investors to harness hard-to-access asset classes, often illiquid in nature, but offering the potential to diversify traditional equity and bond risks.

Will the future continue to echo the past?

The recent death of David Swenson, a pioneer in the evolution of institutional portfolios, gave us cause to examine what the future might hold for discretionary wealth manager or retail investor portfolios, assuming the future continues to echo the past.

David ran the Yale Endowment from 1985 until he died in May 2021 and delivered strong and consistent returns during his tenure. He revolutionised how and what Yale invested in by applying an extension of Markowitz’s modern portfolio theory. He identified eight asset classes (which we will come to later), defined by differences in their expected response to economic conditions, such as economic growth, price inflation or changes in interest rates. Weightings are determined by risk-adjusted returns and correlations.

Yale combines the asset classes in such a way as to provide the highest expected return for a given level of risk, subject to fundamental diversification and liquidity constraints. Aside from setting a diversified strategic asset allocation to these eight asset classes and rebalancing regularly (which some researchers believe has contributed 40% of Yale’s excess returns), the process also rests on manager selection.

Yale’s manager selection process harnesses the expertise of a dedicated team, and looks beyond numbers trying to incorporate an understanding of the motivations, intelligence, character and integrity of each manager.

So far, so not very different (in theory at least). In our view, the key lessons from Swenson and Yale are their very different attitudes to equity risk (with a high tolerance), and their willingness to embrace private markets and illiquidity.

To some extent, their ultra-long term/perpetual investment mandate helps embrace risk and illiquidity. However, it occurs to us that many private client, JISA or SIPP portfolios also have multi-decade investment horizons.

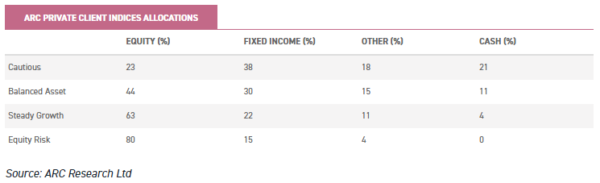

As such, the differences between Yale’s current portfolio and that of the various ARC Private Client Indices are stark. We show below the latest ‘model’ allocations from ARC in which we believe notable is the significant cash and fixed income exposures – even for those with the highest risk.

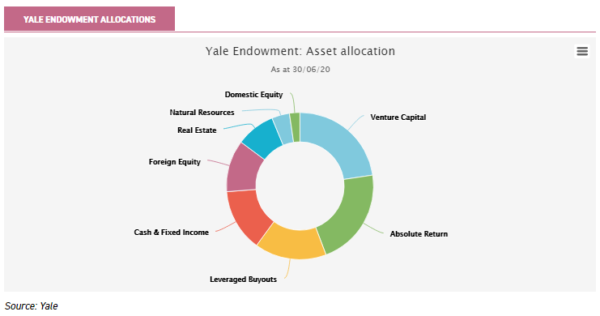

Comparing these models with the latest asset allocation from Yale, the differences are stark. Overall, Yale’s exposure to equity may be seen as roughly similar as the “equity risk” allocation of private client portfolios.

However, the real difference is where Yale gets its equity exposure from. In the chart below we show Yale’s very high exposures to Venture Capital, Absolute Return and Leveraged Buyouts (together 60% of exposure) which we would imagine represent perhaps ten times the exposure that private client or retail portfolios typically have to these asset classes.

These are typically areas of the market that attract significantly higher fees, and with the UK regulator’s attention focussed on overall costs borne by investors, it is perhaps no surprise that these are areas of the investment universe that remain underrepresented in retail portfolios when compared to Yale. Of course, Yale has its enormous size which undoubtedly allows it to negotiate fees down.

However, the same must also be true for its listed equity allocations, and on a relative basis therefore Yale’s team must be facing the same trade-off between known higher costs from these investment areas, and unknown future investment results. In the case of Yale, they have chosen to pay up, and the results show they have reaped the rewards.

Follower of fashion

Yale’s success has prompted many smaller endowments to try to follow the Yale example by adopting a similar asset allocation. David Swenson and his colleagues have regularly warned against a blanket application of the Yale model, and the results of smaller endowments that have tried to adopt Yale’s model have generally been mediocre.

The reasons given of why Yale has been able to maintain its performance lead remain hard to pin down. However, most explanations centre around Yale having first mover advantage (with many of their managers now closed to new investors), the considerable resource and skill that the Yale team bring to bear in manager selection, and the practical consideration of the sheer quantity of capital that those following Yale need to put to work in less liquid, private markets, meaning that their listed equity exposure remains considerably higher than Yale even now.

In our view, none of the reasons given for underperformance apply to a retail investor contemplating the investment trust universe. Investment trusts are by definition pretty much closed to new investment, and many managers do not have similar open-ended funds that are widely available for subscription.

The secondary market offers the entry point – which means for small investors, all trusts are open for business during LSE trading hours for subscriptions and redemptions. With regards to manager selection within the investment trust universe, this is clearly a significant hurdle to achieving returns as strong as Yale’s but, as we have discussed before, we believe the investment trust universe represents something of a ‘premier league’ for investment management talent.

Firstly, there are a limited number of trusts, and it requires demonstrable skill to be awarded a mandate by the independent board. Secondly, the board is there to continually monitor performance, and take action if performance is not maintained.

Thirdly, the structural aspects to trusts give managers a higher chance of performing to the best of their ability, free to invest away from the pressures of inflows and redemptions and liquidity concerns of underlying stocks. The ability of investment trusts to outperform open-ended funds is discussed here. In addition, as we will discuss below, several trusts employ a manager of manager approach, which helpfully gives the non-expert retail investor an extra layer of due-diligence and – one would hope – alpha generation from manager selection.

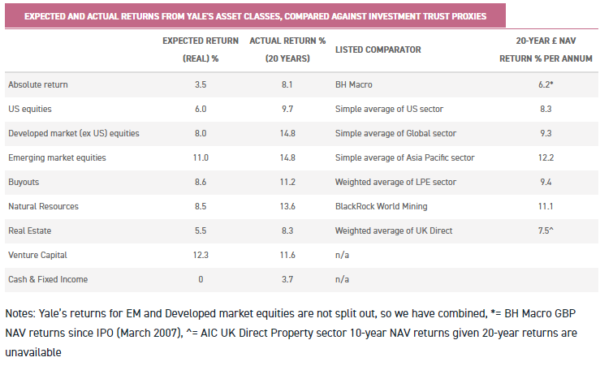

Our contention is that the investment trust universe therefore provides a good source of talent to populate a long term, Yale model allocation, and is corroborated by the table below. Yale provides 20-year returns earned from their asset classes, which provides some comparison problems with listed funds which typically have few ‘pure’ track records with no changes to managers.

However, for what it is worth, we have taken 20-year NAV returns for sector averages, which gives an idea of comparative returns. We think it notable that long run returns for Absolute Return (BH Macro), Emerging and Developed Market equities, Buyouts (Listed Private Equity) and Real Estate trusts are broadly similar to Yale’s returns – especially when one considers that these returns are in Sterling, which has depreciated against the dollar from 1.77 to the current level of around 1.40 over 20 years.

Using investment trusts to take the Yale road

In our view, the main takeaway from our analysis above is that within each of Yale’s asset class buckets, broadly similar returns are achievable from listed funds. As such, investors with long term investment horizons, such as those with SIPPs or JISAs could take a leaf out of Yale’s book and adopt a more adventurous asset allocation framework, more akin to the endowment model.

The biggest change will need to be a willingness to invest in private markets and bear the illiquidity risk this presents. This risk is certainly very present, and during the financial crisis of 2008, several pension and endowments funds with Yale type models found themselves struggling to meet their liquidity needs, in some cases issuing bonds to alleviate them.

Given SIPP investors are by definition paying in rather than taking capital out, they can continue to rebalance the portfolio through annual contributions irrespective of the liquidity of their portfolio (whilst investment trust shares are likely to remain relatively liquid, investors may decide not to exit investments on very wide discounts).

The change suggested by Yale for SIPP investors is certainly dramatic. But it is no more dramatic than the changes made by Yale itself in the 1990s. In 1990, 65% of the Yale Endowment was targeted to U.S. stocks and bonds.

Today, target allocations call for 9.75% in US marketable securities and cash, while the diversifying assets of foreign equity, absolute return, real estate, natural resources, leveraged buyouts and venture capital dominate, representing 90% of the target portfolio. Will investors follow – even just a little way – and take the plunge?

We believe the strong performance of the Yale endowment over the years justifies it and, if history is anything to go by, over time underlying portfolios will become less dominated by listed equities. Indeed, we are already starting to see this trend towards private market investments, but Yale would suggest that the trend has a long, long way to go.

In this regard, investment trust followers have an advantage, with a wide selection of strategies and managers available that give a relatively liquid way of gaining exposure to what Yale call “non-traditional asset classes”.

Yale invests in these asset classes because of their return potential and diversifying power. By their reckoning “alternative assets, by their very nature, tend to be less efficiently priced than traditional marketable securities, providing an opportunity to exploit market inefficiencies through active management”.

They observe that the “endowment’s long-time horizon is well suited to exploit illiquid, less efficient markets”, much like a SIPP or ISA. The great thing is that for non-institutional UK investors with a SIPP or ISA, and a long-term view for investing, there are plenty of strong options to adopt more of an ‘endowment’ model for their portfolio.

How then might one tackle filling each of Yale’s buckets? There are several buckets which are relatively simple to populate from the open-end or investment trust sectors, including domestic equities, foreign equities, cash and bonds, real estate and natural resources (which we take to include commodity exposure). Those who wish to find suitable absolute return funds might consider BH Macro (in the process of combining with BH Global), some of the constituents of the AIC Flexible sector (click here to read our recent editorial on the sector) or any of the plethora of absolute return UCITs funds.

We now turn our attention to what we view as Yale’s real differentiator to traditional portfolios, being its 35% target allocation to venture capital and leveraged buyouts.

Nothing ventured, nothing gained

Unfortunately, there are relatively few directly comparable avenues for the venture capital allocation, which Yale target at 23.5% of its portfolio. Yale’s venture managers provide exposure to innovative start-up companies from an early stage. As ‘envogue’ this area is currently, it is undeniably a high-risk strategy – Yale expects long term real returns of 12.3% per annum but with risk of 37.8%.

Over 20 years, Yale has achieved 11.2% per annum from its portfolio, which might be considered a little disappointing given the risks involved. The AIC’s Growth Capital sector is the most obvious avenue to explore, but it is worth remembering that trusts in this area do have relatively short track records and that it takes time for managers to see the fruits of their investing labour harvested.

Other trusts which offer an exposure to venture include Third Point Investors (TPOU), the board of which has recently approved an increased allocation to venture and private equity up to 20% of NAV. Third Point is developing a strong track record in the venture space, with one of its investments recently achieving an IPO.

SentinelOne’s first day of trading valuation was more than 100 times the valuation at which Third Point first invested in 2015, illustrating the potentially explosive returns achievable from venture. This is the second high-profile IPO from Third Point’s portfolio, with AI-driven lender Upstart having been listed since December 2020 and appreciating more than five times in value since.

As we discuss below, venture is a differentiated strategy to private equity, but HarbourVest Global Private Equity (HVPE) has the highest allocation of the listed private equity trusts, with 35% of NAV represented by ‘venture and growth equity’ funds. Other trusts which might be considered as having exposure to venture capital include RIT Capital Partners (at least 8.9% of the portfolio represented by venture capital funds) and Scottish Mortgage.

Buyouts

Yale’s leveraged buyout allocation represents a similar strategy to those employed by the listed private equity (LPE) sector, which offers a wide range of different approaches to access what Yale believes are “extremely attractive long-term risk-adjusted returns” from a strategy that “exploit[s] market inefficiencies”.

Yale’s leveraged buyout portfolio is expected to generate real returns of 8.6% with risk of 21.1%, and over the past 20 years has delivered 11.2% p.a. In many ways, the LPE sector offers a better access route than Yale has, given the fact that an investor today is able to buy into funds which have established portfolios of investments, which in some cases are very mature.

In contrast to secondary private equity transactions (in which an institutional investor will buy a fund interest off another investor at a negotiated price) which typically attract a small discount or premium to NAV, most LPE trusts trade at material discounts to NAV.

Other advantages the LPE sector has include the ability of trusts to make accretive share buybacks and pay dividends (which represent a form of capital return at NAV). At the margin, this enables trusts to re-invest in their own portfolio at times that they trade at a considerable discount to NAV.

Recent examples include ICG Enterprise (ICGT) and Oakley Capital Investments (OCI) which both took advantage of their strong balance sheets and the share price falls in 2020 to make opportunistic and highly accretive buybacks. Related to this point, managers of LPE trusts are experienced at cash management, a very important consideration for investors in the trusts.

The illiquid nature of private equity investing is that the timing of specific investments and realisations are very hard to predict. This means that for traditional investors (i.e. not through LPE trusts) in private equity, they need to have liquid and easily accessible funds available should a manager ‘call’ on the capital commitment the investor has made.

This means that for a notional amount of capital allocated to private equity, the amount actually invested is always smaller, and means that the high headline returns private equity managers make on a deal-by-deal basis, never translate into as high returns on the capital allocated. With the LPE sector, the ‘cash drag’ effect is often minimised through conservative over-commitment strategies, and the use of arranged (but rarely drawn) credit facilities.

It is perhaps because of these advantages, but also the high quality of management within the LPE sector as a whole that has enabled the fund of fund sector (on average) to deliver similarly strong returns as those delivered by Yale’s buyout managers.

We believe that buyouts represent a lower risk proposition than venture (a view shared by Yale). The LPE sector, as listed funds, also have a much more established track record. Private Equity investing is different from venture, in that private equity managers control their companies, enabling them to set the strategy, drive value creation and perhaps just as importantly, decide when to crystallise value by selling.

It is this highly active ownership that has meant that private equity managers have generated strong outperformance through cycles. Private equity investing creates value in a repeatable process over cycles. The reasons behind this are many, but we believe the key drivers include:

Long term thinking – fund structures often have investment periods of up to ten years, meaning that private equity managers are able to take a longer-term view when making investment decisions. They can afford to be more focussed on fundamental long-term value creation than achieving short term profit targets.

Stock picking – given the illiquidity of investments, putting capital to work requires a huge upfront research and due diligence effort. Over the past few years, many LPE trust managers we have spoken to have said they have been biased towards “defensive growth” companies. Their forethought has been vindicated by performance during 2020, which has seen LPE trust NAVs demonstrating significant resilience when compared to wider equity markets.

Alpha – private equity managers are often sector focussed and have detailed knowledge of the competitive landscapes within sectors or niches. Aside from buying businesses, their job is to provide on-going focussed strategic and operational guidance including expansion into new markets or business lines, or identifying potential bolt-on acquisitions. They typically have significant financial and capital markets expertise, which wouldn’t normally be found in such businesses.

Alignment – incentivisation structures for private equity backed businesses are based almost entirely on equity, and base costs are kept as low as possible. This is the case for both the private equity backers as much as for the management teams of the businesses they invest in. Both are highly motivated to generate cash returns (rather than mark to market valuation gains) over the life of the investment – both in terms of success-based remuneration and in terms of their future careers.

First steps in a move towards Yale

As possible evidence of the acceptance of private equity’s attractive attributes in a portfolio context, the venerable F&C Investment Trust has long had a commitment investing in private equity as part of its global investment approach, which now sits near 10% of NAV.

Those investors who wish to start to move towards an endowment model might consider being even bolder, and allocating up to 20% of their portfolio into LPE trusts in place of equity exposure allocated elsewhere. This would mark a very significant divergence from traditional portfolios which we understand might have between zero and 5% invested in LPE trusts.

The LPE sector offers a wide range of different approaches and slants, which means that investors wishing to make a meaningful allocation can easily diversify their exposure to managers, sectors and approaches. In the table below we split the universe by the way each trust makes its investments.

Direct LPE trusts have a single management group making investments, and tend to have very concentrated portfolios which in turn exposes investors to higher specific risk and potentially higher rewards. On the other end of the spectrum are the highly diversified fund of funds which have underlying exposure to many thousands of private companies. Between these two poles, LPE trusts have more concentrated portfolios, but relatively little specific risk to individual companies. Investors can choose between these depending on risk appetites, sector preferences and premiums/discounts to NAVs.

As we highlight above, the trusts within the LPE sector provide a wide range of different exposures. Whilst all operate in the same broad area of private equity investing, and will likely be subject to the same broad market sentiment driving premiums and discounts, they have many complementary attributes with each other which enables investors to build a relatively diversified exposure to the space.

ICG Enterprise (ICGT) offers a hybrid approach to private equity investing: with around 52% of the portfolio through third party funds and 48% within the ‘high-conviction’ portfolio where ICG has directly selected underlying companies through co-investments and through ICG funds.

Third party fund selection is centred around identifying top quartile private equity managers who ICG believe are more experienced, longer-established and invest in larger, more resilient buyouts. Investments with third party managers drive co-investment opportunities, and enable diversification within the portfolio, without it becoming too concentrated.

Over time, ICG’s team have added value through selecting top-tier managers in the fund portfolio, or through good company selection in the high-conviction portfolio. The combination has meant that ICGT has delivered consistently strong value creation for shareholders. This is reflected in ICGT being on track to deliver its 13th consecutive financial year of double-digit portfolio growth. For much of 2019 the discount remained narrower than 20%, but currently trades at c. 29% discount, which looks good value from our perspective.

NB Private Equity Partners (NBPE) offers a unique approach within the London listed private equity (LPE) sector, focussing on equity co-investments. These are equity investments made alongside third party private equity sponsors and have generated strong returns for the fund. As such, NBPE has a wide spread of investments across sectors, companies, and private equity managers – including 64 core investment positions (those greater than $5m) made alongside 38 different private equity sponsors (as at 31/03/2021).

Making these investments directly means NBPE’s investors only pay one layer of management and incentive fees. As has been reported by many trusts in the LPE space, realisation activity within the portfolio has been very strong this year, leading to significant NAV growth. As well as driving NAV growth, realisations have meant that gearing has reduced substantially, and is likely to continue to move lower.

Over the long term, Neuberger Berman’s impressive team and dealflow should enable NBPE to continue to offer exposure to what they see as the cream of private equity deals, and enable investors to compound investment returns over the long term. The discount of 23% is in line with many of the fund of funds in the LPE sector, which we believe does not properly reflect NBPE’s prospects. With the portfolio looking increasingly mature, the momentum behind realisation activity seen over recent months could continue.

BMO Private Equity (BPET) offers investors a distinctive approach to accessing private equity, investing with managers at a relatively early stage in their development. BPET’s manager believes this means being exposed to more motivated teams and to lower mid-market deals where BMO is more likely to be offered co-investment opportunities.

We expect the level of co-investments to remain between a third and a half of NAV, reflecting a rise in the number of opportunities that BPET’s managers have observed in this area over the years. From a top down perspective, the team aim to manage risks by deliberately diversifying across companies, funds and managers.

BPET has a track record of delivering good returns and, in contrast to peers, was trading at a premium to NAV for several months during 2018, but also most recently in January 2020. 2020 saw the discount widen dramatically, but has partly recovered some of the lost ground and now trades on a discount to NAV of 17%, a slight premium to peers.

As part of a diversified portfolio, the higher returns generated by directly invested private equity trusts can be attractive, notwithstanding the greater volatility of returns. HgCapital has a well-established track record as a directly invested private equity trust.

The managers specialise in software and business services in Europe, and taking all of manager HgCapital’s investments together would result in the second largest software firm (by market capitalisation) in Europe. The trust has delivered strong long term returns for shareholders, perhaps a reason behind the 15% premium that the shares currently trade at.

Many of the same dynamics behind HgCapital trust’s growth have benefitted the underlying portfolio of Oakley Capital Investments (OCI), which focusses on European technology, education and consumer sectors. Digital disruption and the opportunities it presents has long been a recurring theme in OCI’s portfolio.

This placed OCI well at the beginning of 2020, and portfolio companies have clearly been nimble in adapting to the digital opportunities presented to them during lockdown. 53% of the portfolio by value had digital delivery models at the start of the year, which had risen to 76% by the end of 2020. Entrepreneurial founders of businesses represent a key part of Oakley Capital’s DNA, with a track record of being the first institutional investors in growing companies.

The Oakley network is key in helping the team access compelling investments at attractive valuations at a time when competition is strong. OCI’s strong balance sheet is also a differentiator, having gone into the market sell-off with net cash of 36% of estimated net assets. This put the trust in a strong position, and Oakley Capital has made a number of interesting investments since then.

Cash now represents c. 22% of estimated NAV. Oakley’s track record is strong – both in absolute terms, but also relative to peers. For investors who want a focussed private-equity portfolio, we think OCI looks exposed to plenty of exciting growth drivers from its Portfolio of niche businesses that are leaders in their field. The shares trade on a discount to the historic NAV of 12%.

Conclusion

We believe that the Yale endowment highlights where the future might be headed for non-institutional investors. Yale’s objectives, and its willingness to look to the very long term echo the objectives of many SIPP investors. The key lessons from Yale for such investors is to embrace equity risk and illiquidity, to enable underlying managers to exploit inefficiencies and generate superior long term returns than listed indices.

Whilst Yale’s largest allocation is to venture capital, listed fund investors do not have a particularly deep sector to pick from to access this asset class. At the same time, Yale anticipates it carries nearly twice as much risk as listed equities, and so investors wishing to start to emulate the Yale model might do well to focus more on the other significant private market allocation – that of leveraged buyouts.

The LPE sector has a wealth of options for investors wishing to access this area of investment, and the historic returns generated by the peer group have broadly matched those generated by Yale’s portfolio.

We believe most traditional investment portfolios only have a cursory exposure to these areas, and so most investors trying to shift towards a Yale model could start by replacing conventional (i.e. public market) equity exposure with LPE trusts. Short term, the effect at a portfolio level is unlikely to be felt significantly – for better or for worse – but over periods measured in the decades, the compounding effect of private equity value creation should add considerably to portfolio returns.

That many LPE trusts are on a discount is an indication that UK investors have not caught up with Yale’s long held philosophy. If they do, it may be that LPE’s superior returns are reflected in premiums rather than discounts to NAV. As Yale has experienced, having first mover advantage can have a lasting impression on your portfolio’s returns.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.