Apr

2024

What’s the best way to get invested in equity markets?

DIY Investor

2 April 2024

Is it better to jump in all at once, to average-in over time, or to wait for a market correction? By Victor Haghani

Decide your desired long-term allocation

You first need to figure out how much to allocate to equities, which will depend on your view of the expected return and risk of equities and your degree of risk aversion. Over a long horizon, equity markets are driven by earnings and dividends, which are easier to predict than sentiment-driven short-term changes in valuation.

Many analysts currently estimate the world equity market has a long-term expected compound return above inflation of around 4% to 5%, based on today’s earnings yield of about 5% and dividend yield of around 2.5%.

You’ll need to combine your expected return estimate with your view of the risk of owning equities and your risk aversion profiles to arrive at a target that feels right to you. All else equal, it will be higher or lower depending on your forecast of the return of equities, and only if your expected return is zero (or negative) would you want to have no equities at all.

How much to worry about the short-term?

If your short-term forecast is different than your long-term one, it is the short-term one that should primarily drive your decision. Unfortunately, there’s a lot of evidence warning us that it’s very difficult to forecast short-term equity returns, as conveyed by the axiom, ‘time in the market is more valuable than timing the market.’

When equity markets are cheap, measured by any of the common valuation multiples, future returns have been higher than when they are expensive. Although this is already accounted for in long-term forecasts, some investors worry that short-term performance is more dependent on valuation reverting to fair value than is actually the case.

While we don’t have enough historical data to draw precise conclusions, what we do have suggests that the commonly used valuation multiples don’t give us much help in predicting short-term performance.

For example, if we look back over the past 130 years of U.S. equity market experience when P/Es were in the highest decile, subsequent one year real returns were lower than average, but still had a mean positive annual return of 3.4%. This is not to say that you can’t have an expectation that equities are going to go down 10% next year, in which case you really shouldn’t own any equities at all. It’s just that if you think equities are going down next year, based primarily on equities being overvalued, know that history is not on your side.

The benefits (and cost) of wading in gently

Once you determine the right allocation, should you immediately make the adjustment and move your allocation to the optimal point?

An incremental adjustment over time (‘averaging-in’) is not financially optimal. However, averaging-in provides a psychic benefit; if the markets go up over the period that we’re averaging-in, then we’ll be pleased we got some of our savings invested at the beginning, and if the markets go down we can be happy we didn’t move all the way right at the beginning.

When does ½ = ¾?

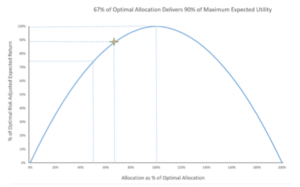

Building up your allocation to the desired level over time leaves some expected return on the table. But, from an expected utility framework, the cost is quite low. This is because as we increase our allocation to equities, our expected gain goes up in proportion to our allocation, but the cost of risk grows faster than in proportion to our allocation.

In the case of the most popular family of utility functions, it goes up quadratically, that is, in proportion to the allocation squared. In other words, we should require four times the compensation to bear two times the risk.

Thus, moving halfway to an optimal allocation gets approximately three-quarters of the value of going the whole way, and going two-thirds of the way to optimal gets us about 90% of the value of going the full distance.

Recall also that at the optimal point, the risk-adjusted return of our investment is equal to half the gross expected return. Combining these two effects means that averaging-in to your optimal allocation costs relatively little in terms of risk-adjusted return.

Warning: not all averaging-in plans are created equal

The averaging-in I’ve been discussing is a disciplined program of investing a fraction of your savings into the market regularly, over a pre-defined period.

Some investors are attracted to the idea of contingent averaging-in, where they plan to increase their allocation to equities only if they fall below some target price level. The problem here is that the investor is taking the risk of the market going up and never (or at least for generations) coming back down again to the target level, and thereby incurring a very significant opportunity cost. For an idea of how bad this can be, we need only think about an investor who in early 2009 set a target 10% below the level of the markets, and is still waiting to invest while investors who averaged-in to the equity markets nearly tripled their investment.

Conclusion

Once you’ve decided on your target allocation to equities, ideally with greater weight on the long-term return driven by earnings and dividends than on predicted short-term expected changes in sentiment, the next step is to decide how to get to that target.

Choosing a plan is ultimately a matter of personal preference, as any approach other than moving straight to your optimal allocation is financially suboptimal.

However, some plans are less sub-optimal than others. For example, averaging-in over one year has quite a low expected cost. More efficient still would be to immediately move about 50% of the way to optimal (thereby getting 75% of the benefit), and then moving the rest of the way over the course of a year.

At the other extreme, following a contingent plan that only goes into action when the price of equities drops by some threshold amount is a risky approach with a high expected cost. In the end, any plan is a good one if it overcomes the inertia and anxiety that holds you back from your chosen investment destination.

Once you’re in for a while, another powerful human trait, forgetfulness, will make you wonder why you spent as much time as you did contemplating the plunge.

Commentary » Equities » Equities Commentary » Equities Latest » Latest » Take control of your finances commentary

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.